We

arrive in New Orleans on Friday around lunch time, three hours after saying

goodbye to the kids and catching our flight, staying in a majestic old building

along the Esplanade, in the Treme neighborhood, mysterious trees and gas lights

along the promenade, Buffa’s, our favorite spot just down the street.

Its

hotter than ever, but people are still on the streets, taking it a little slow.

“How

y’all doing?” a man greets us strolling along.

“All

right,” I reply.

“People

say hello to you here,” I note with Caroline. Miss that in New York, where most

everyone is too busy being professional or scolding their kids to greet you.

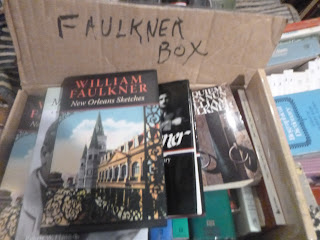

We

were in town for the Faulkner Wisdom conference, our

second year in a row, talking writing and the places that inspire our

stories. My

novel that I submitted to year’s contest will be out next year. But editing

it is a bear. A quarter century later,

its still a struggle to find the right words. In this sentiment, I’m certainly

not alone.

As

the master wrote about writing The Sound

and the Fury, one of the novels I carried along.

“I

wrote the same story four times,” confessed Faulkner. “None of them were right,

but I anguished so much that I could not throw any of it away and start over so

I printed it in four sections. That was

not a deliberate tour de force at all.

The book grew just that way. That

I was still trying to tell one story which moved me very much each time I

failed but I had put so much anguish into it that I couldn’t throw it away….

And that’s the reason I have so much tenderness for the book, because it failed

four times.”

Faulkner

is the nut I’m always trying to crack. Described as a Latin American writer

from the South, he created a mythic land that writers from Columbia to Buenos

Ares to Lima to Sewanee seemed to understand and borrow from to conjure a not

quite manic realist image of the world.

Dad

used to teach Faulkner when he at Sewanee. Our stop is Galatoire’s.

I

always get excited walking there, looking at the gas lamps, the streets signs,

the Spanish Streets of this far away space, that looks like no other city.

“It’s

a narcotic miasma of voodoo, a swamp of influences,” notes Kurk, my friend from

New York, who lives here now.

We

make it past the blues bars and pubs to Galatoire’s, where the old joint feels

a bit like a scene from another time and this time, with old-world waiters and

elegantly dressed people, a festive spirit crackling. People are reciting poetry. We enjoy some

gumbo and pompano and toast the old man. Its Caroline’s third trip here with me. A

part of Dad is always here for me.

“New

Orleans is a city with the clap,” Dad was prone to say, borrowing his best

friend’s words, to describe the place.

“Everyone in this good city enjoys the full

night to pursue his inclinations in all reasonable and unreasonable ways,” notes

an editorial in the New Orleans Times Picayune,

1851.

Certainly,

my friend Rob did when he visited the city, writing one of my favorite short

stories of his, about that time, and the dance between eros and Thanatos which

takes place here. In between self-immolation and alcohol, an elder heiress and

a younger writer, his story takes shape.

He writes:

We

all have our stories here.

People

start clapping for a 90-year old man celebrating his birthday at Galatoire’s,

the room breaking out in applause.

Caroline’s in the bathroom. Dad

only made it to 77, spending countless nights here, doing much of the same the

same as Rob, reading and thinking and leaving a trail of influences.

Stop

it, Caroline counsels when she arrived back the table, encountering me mumbling

to Dad.

Stop

drinking. Lets get out of here. She puts down my glass of pouilly-fuissé

Caroline

and I thank Sheldon on our way out. He’s

worked here since he was 15.

Now

you have a waiter here, he tells us.

Call

me next time you come back ok?

Thanks.

Pirates

Alley is just down the street.

The

air helps, even if much if it smells of the familiar aroma of mildew and vomit

one comes to associate with New Orleans in general and Bourbon Street in

particular. Its still a place for

burning ambitions, memories, and such.

Most

of the books say don’t come here. I

totally agree.

But

I’m still drawn to this space we used to visit as a family.

Dad

smiled here like few other places.

He

enjoyed the food and the voodoo, the music and the heritage.

That

is your church, he told me as the trumpeter played in my ears at Commander’s

Palace when we were kids.

Down

to Jackson Square we walk, sitting in the moonlight, watching people arrive for

the haunted houses, ghosts and vampire tour.

We

have to bring the kids next time.

The

moonlight shone on the old square where Rob began his tale, like so many of us,

making is way into the Cabildo to avoid the storm, up the majestic stairs, stumbling

through the history of this place where the French sold us Louisiana, pirates

were jailed, and ideas were born..

“It’s

a great short story,” notes Caroline, reflecting Rob’s story and by extension

the self-destruction of all writers. We

all struggle to find a voice with this cacophony.

After

sitting for a bit, we walk through the alley where Faulkner lived, writing his

first novel, Soldier’s Pay in 1925,

another bad boy finding himself with the oddballs and characters. Faulkner and

friend and landlord, Bohemian bon vivant William Spratling shot paint pellets

at nuns and prowled through the old neighborhood, poking fun at their

contemporaries. He arrived as a bad poet and left a master, not that I ever

really understand much of what he’s saying in Absalom, Absalom! or Sound

and the Fury.

Lets

go to Buffa’s and have a beer, suggests Caroline.

So

we make our way back past the crusty punks on Esplanade to the old road house

for a final pint of the night.

It

doesn’t take much to make friends at Buffa’s.

“Benjamin

Shepard from Brooklyn New York,” I greet everyone, walking in. And that’s all

it takes.

Pete,

the amiable bartender who is there every time I come, greets us bringing us

Albitas. The set has just ended and a

few musicians and their friends are standing by the door.

We

all chat for hours. I help the band take their equipment outside. They’ve got a gig in Mississippi the

following day. So they have to leave

early, but not too early for another round.

As

Caroline talks with the band, a younger woman tells me about her life after the

storm.

I

had a psychotic break and was hospitalized.

But

now I’m finding my footing, studying social work, doing an internship, she

tells me.

That’s

good. It helps to be a little crazy.

You

gotta learn who people really are, she explains. This city will always remind you.

A

woman our age sits down with Caroline and I.

We

tell her we’re ready to move here.

We

just need to get the kids through school.

That’s a good thing.

This is a spiritual mecca, she replies. We all come here to find

something. Get those bitches through school and come back here. She smiles at

Caroline. Isn’t this an incredible moment we’re happening?

A

new band starts a set.

Half

way through the set, we go. Sleeping for a bit, I wake at 3 AM, drifting in and

out for the next few hours. Its been like that for weeks. New York always reminds me there is something

I have to do, even when I’m here.

The

next morning, we take it slow, enjoying a morning coffee on the balcony, with

the trees, before leaving for the day.

Our

day begins with a stroll through the Marigny,

for a bite at the Flora coffee shop and gallery, across from Mimi’s, over to

the New Orleans museum and back to the Cabildo for the Faulkner opening at the Cabildo.

Looking

out at the majestic city, I greet Rosemay James, a co-founder of the Faulkner

Society.

Rob

says I.

Oh

he’s such a bad bay, she smiles back.

Place

has long been an inspiration for literature here, spawning Faulkner and Percy

and Sherwood Anderson, Rosemary introducing the conference. She lives next door at Faulkner’s old house. It

was a sleepy place in the 1920’s. It was

an inexpensive place, full of characters, and a place where Faulkner found his

voice. When he came here he was down; when he left he was a star. The world

never intruded upon Falkner here. And he

thrived here, notes Rosemary.

Often

referred to as the Northern most city in the Caribbean, NOLA an entry point for

rum, trade, imports, people and ideas making their way North up the

Mississippi.

“I

feel immediately home here. The weather

feels familiar,” notes Ingrid Contreras, a writer from Columbia and author of

the book The Fruit of the Drunken Tree, in her talk on the places left behind as

a muse for literature. She left Columbia

only a few years ago, writing the book when she got to Chicago, where she

reflected on her struggles as an immigrant. We believe in place here. This is where we find our identity. She had to spend three years in North

American soil before she could become naturalized here, she explained; it paves

a way to citizenship. During those cold

Chicago winters she reflected on the places she left, haunted by her former

life, and what caused her to leave, even as that place was changing. In this way, she suggested she suggested her mind

was in both places, one imaginary and one real.

Listening,

I

think of the South I left behind to move to San Francisco in 1992, and that

period of becoming a writer in San Francisco, reflecting on the places and

ideas of the South, the friends and comrades I had to leave behind find

something else. Midway through my

novel about the period, the chapter, “To Lose

the Earth You Know,” charts this feeling.

The title is, of course, a reference to Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again, where he

writes:

“Something has spoken to me in the night...and told me that I

shall die, I know not where. Saying: ‘[Death is] to lose the earth you know for

greater knowing; to lose the life you have, for greater life; to leave the

friends you loved, for greater loving; to find a land more kind than home, more

large than earth.”

From

time to time, we all lose the earth we know for greater knowing. That is what

leaving, what going West, what traveling, up and down the Mississippi, from Cartagena

to Chicago is all about.

NOLA

writer Walter Isaacson continues the theme of place as a muse for literature.

“What

are the ingredients that make it a creative place,” he wonders - layers of

ingredients that are enriched by waves of people, the French, the Spanish, the

Haitians. Its not a melting pot, it’s a

gumbo, a vibrant mix. That’s true of

literature, the food, as it is of music. The decommissioned musicians after WWI

who created brass bands, on top of Ragtime, and French Opera. The essence of

democracy is layers we pull together, creating a rich culture. It works best when its celebrity, welcoming

new voices in, and celebrating them, embracing that mix. This has often been

the case. But there were the

regressions, the Reconstruction when the Robert Lee statue was erected, the

downtowns of people, the storm when the city was under water. It’s the juxtapositions that get to you, he

argued paraphrasing from the patron saint of New Orleans literature, Walker

Percy. They create sparks and frictions, ions charged, before the storms move

in. Those are the times when we remember

what is most important, that we are all in it together. We need each other. Unfortunately, those moments pass and we

separate from each other. But its better to stick together. Percy showed me you could be a writer. I had never known that was possible. There

are two types of people here, the characters and the storytellers. Its better to be a storyteller. Let me tell you a story, that is what makes

our literature, the sparked ions. That

storytelling helps us come to grips with the water coming in from all sides, a pimento

that keeps coming through.

He

recalls that Louis Armstrong was elected king of Mardi Gras in 1949, receiving

no small amount of flack for wearing black face in the parade. The people here deal in symbols. They

understand, he explained at the time.

Thank

you Louis.

The

biproducts are many, especially when our stories contradict themselves. Multiple

personalities is not a disorder in this city of masks, writes Rosemary, it’s a

byproduct.

And

this is probably why we all miss New Orleans?

Standing

up as the session ended, we stumble into my old friend Kurt from New York,

whose moved here. He introduces us to

Martha, his friend, another writer, struggling to contain her story, like we

all are. War and love, Viet Nam her story is unique and tragic and wonderful.

But the telling is anything but simple.

She and Caroline commiserate.

Back

to Pirates Alley, we walk, not for the absinthe that Rob describes in the

story, but for rum and beer and more stories. Caroline and Martha commiserate

and Kurt and I catch up.

That’s

for the absinthe, I ask the bartender, pouring drinks through the spouts.

You

got it.

Off

to Coops we walk after drinks.

Do

you remember coming here with Dad I ask.

No.

We

came here a lot.

Looking

around the old eatery on Decator, I flash back that last few times I was here

with Dad, walking back from Café du Monde, listening to steel drums. New

Orleans was our magic, nuzzled a few hours West of the treachery of the Atlanta

we were leaving, on our way West to a new life in Texas, where we were going.

We always brought a bit of ourselves along the way. But it didn’t stop us from

taking a pause here.

It

was a time, a place to be alive and explore the magic.

“Everybody talked about Freud when I

lived in New Orleans,” gossiped Faulkner. “.. but I have never read him.

Neither did Shakespeare. I doubt if Melville did either, and I'm sure Moby Dick

didn't.”

The

city is not the same, a man confessed to Dad and I after we toured the wreckage

from Katrina, that was a decade ago.

The

last time we were here together, was in 2014, when the bartenders toasted to

Dad’s earn, pouring beer on the floor for him. The lines between what was and

what is of him, becomes blurry as the years pass.

And

then I’m back. Footballs playing. Some black girls order friend shrimp.

I

have a jumbalya.

A

man to my left is finishing gumbo.

He looks like Arlo Guthrie.

Caroline

has red beans and rice.

Life

could not be better.

Back

to Buffos Caroline and I walk.

I

take in another set.

She

goes back and I join.

I

have no idea what he’s talking, reading the Sound

and Fury out loud in bed. The

monologues of Faulkner’s anguish are many. Is Benjamin 33 or 3 or 13? Its not

easy to tell.

The

sleeping badly only continues as I stumble off, down, back, up at 11, moody, and

back down and up at 3 and back down. New

York murmurs in my mind. Is it possible to

live another way, without New York thoughts pulling at you at two am? Are there other ways to be? Those old ghosts of who we have become are

hard to shake.

Caroline

spends all morning at the conference.

So

we meet at lunch at Bacchanal on 600 Poland in the Ninth Ward.

“A wine shop that opened up a

beer-garden outdoor space with Christmas lights strung over cheap outdoor

furniture, all relaxed, could (and often do) sit there for hours and hours [with]

GREAT live music outdoors,” notes our guidebook. “Focus on fresh organicky

stuff, very fine food …” Its “a wine laboratory where food music and culture

collude with Holy Vino to create the most unique evenings you will ever

experience in New Orleans Ninth Ward.”

The sky is blue as far as one can

see.

“It’s a small world after all”

declares some graffiti outside.

Inside, we order a bottle of rose

wine and sit to enjoy a gig by the Tangiers Combo, clarinet and ukulele.

Carline reads me chapters of her

novel in between sets.

And the band plays the best version

of “I Love Paris” I have ever heard.

Screaming Jay Hawkins’ rendition echoes

through my mind, the layers of influence pouring over me, mixing with the wine and

the moment.

We talk with their clarinet player

after their first set.

“Sidney Bechet was a huge influence

for us,” he explains, alluding to the American clarinetist who lived in the

Seventh Ward here. We hang, chat and

listen well into the afternoon taking in their next set. The sun shines and we

sit under a tree before making our way out.

It was our second year in a row to

try to go to the Confederate Museum, only to find it closed.

We’re not really sure they want us

to see what’s inside.

History’s lessons are many here,

even the stories that are not ready, the histories concealed. Similarly, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art

was next door was full of treasures and absences. There’s so much there. But

there could be more. The history of the

place, its interconnections between cultures and conflicts, that is so well

documented in music and literature, feels absent in the visual arts here, at

least here.

Is the city full of characters from

Richard Lanklater movies, Caroline gushes after the cab driver tells us about

his old boa constrictor who he fed mongooses until he died, playing loud

orchestral music on the way home. He tells

us about his favorite trees in NOLA. But

he worries the city is dying. It used to be great city, he tells us.

“New Orleans is going to be our

Atlantis,” notes Kurt’s friend, over dinner at Buffo’s later that night. “We lose a baseball field a year in open

space that is consumed by the ocean as the sea moves in. There is no future people. People cannot expect to hold property for any

longer periods of time.”

Its an opening and a closing space,

with old categories crumbling as new ones take shape in a dialectic interplay. The

left loves stories of apocalypse.

But I still adore it.

I can see in your face you want to

come back here, notes Kurk.

Yes, I do. Yes, I do.

More jazz, more talk about Mardi

Gras.

Pete, our amiable bartender, brings

us a bowl of alligator etouffee.

Without a doubt my favorite meals in

New Orleans are from here, Caroline gushes, enjoying the meal. Red beans and rice were gone, eaten the night

before. This would suffice.

The conversation continues well into

the evening and then the next day at the final Faulkner lectures we were going

to attend. Its not quite one of those evenings that Kate Chopin describes

here. But we’ve chatted for hours.

“How much can we escape conventional

thinking and actually grasp at freedom,” wonders Christopher Love, in his talk

on place in the work of Melville, Faulkner, and Updike. The idea can be scary. There are places like a raft on a river or

the sea where the reimagining can take place..

To bring them home to the real, that’s a larger challenge. Bartelby grapples with

that. How much freedom can we entertain?

The place has to be epic to hold it. Like the sea, it has to be a place

that can tolerate a lot of contracitions.

A subtext of the conversations

involves Melville and Hawthorne’s friendship.

For a long time, they were the best of friends. But their correspondence grew short.

Hawthorne grew weary of Melville and his obsessive compliments. He did not feel like the American Shakespeare,

but Melville called him that. And he cut

him off, burning their letters. Some

speculate Melville made a pass at the author or his wife. Others wonder if he

became just a little too irritating for comfort. Everyone pays a price.

Friendships erode once they have concluded their usefulness. People move on.

Freud disengages Fleiss.

Certainly, Pierre did, notes

Chrispher Love, referring to Pierre; or, The Ambiguities Herman Melville’s

novel, first published in New York in 1852.

His relationship with Hawthorne was done.

“Pierre little foresaw that this world hath a secret deeper

than beauty, and Life some burdens heavier than death.”

Pierre’s experience’s echoes Melville’s.

“For in tremendous extremities human souls are like drowning

men; well enough they know they are in peril; well enough they know the causes

of that peril;--nevertheless, the sea is the sea, and these drowning men do

drown.”

Writing was about anguish, confesses Faulkner. Its like that for all of us. I feel it editing through typos and bad

sentences, hoping for a good line every once in a while, trying to sleep,

waking too early, writing, drafting new drafts, trying to make it through the

night, remembering past places, waking groggy, hoping for new one’s trying to be

complete in my own self.

Like Melville, Faulkner creates a mythology – a place, a

concept, a lost space - Yoknapatawpha County. But he loved New Orleans:

"Jackson Square was now a green and

quiet lake in which abode lights round as jellyfish, feathering with silver

mimosa and pomegranate and hibiscus beneath which lantana and cannas bled and

bled. Pontalba and cathedral were cut from black paper and pasted flat on a

green sky; above them taller palms were fixed in black and soundless

explosions. The street was empty, but from Royal street there came the hum of a

trolley that rose to a staggering clatter, passed on and away leaving an

interval filled with the gracious sound of inflated rubber on asphalt, like a

tearing of endless silk."

He saw the South as a space a crossroads, something drastic

and radical pulsing through this space in history. A mystic space, resisting

change, it struggles between new and old myths, pulling in converging and

diverging, incongruent directions. There is an unsettled meaning in the place

merged between the real and imaginary.

NOLA never had a monopoly on creative writing, notes Scott S

Ellis, author of the Faubourg Marigny of

New Orleans and Madame Vieux Carre: The French Quarter in

the Twentieth Century

But for a long time it

had a number of the ingredients to entice creatives to write. Misfits were

everywhere, along with cheap rents and magic emanating from the full moons, hot

afternoons and rainstorms where an hour opened up a space to contemplate forever.

As Tennessee Williams put it in Streetcar Named Desire: "Don't you just love those long

rainy afternoons in New Orleans when an hour isn't just an hour - but a little

piece of eternity dropped into your hands - and who knows what to do with it?”

With change coming at a glacial pace, the city maintained a

space for lazy afternoons, daydreams, keeping of tradition, obscurity, and

freedom. But flux did come. We ate

dinner with Dad at Galatoire’s two days before Katrina hit. And all those old

ghosts came out again, the world dragged their feet, and water rose. The world

always has a way of creeping up onto these shores.

We left New Orleans then, as we’ve have again and again,

always hoping to return, trying to make sense of all the stories, the tales we

carry with us, the manuscripts, the dreams, the clouds looming in the distance,

the ways of sleeping badly on our way back home.