“There is nothing more alienating,” writes Lauren Berlant, “than having your pleasures disputed by someone with a theory.” We’ve also had someone say it: you can’t think that; you can’t do that. A belief or theory, one form of morality or another, tells us so. Alienation expands, especially lately. A week in isolation here, a shuttered public space there, an estranged contact, on and on. Berlant shuffled off in June, one of countless luminaries to transition into the great unknown this year. Their essay, “Sex in Public,” surprised me in countless ways. It reminded me, publics are there for all of us to rethink what it means to be alive, to connect with others, and see the world as a large interconnected web of ideas and practices. Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner (1999) wrote: “By making sex seem merely frivolous, merely personal, heteronormative conventions of intimacy block the formation of non-normative public sexual communities… Making a queer world has required the development of the kinds of intimacy that bear no resemblance to domestic space, to kinship, to the couple form, to property, to the nation.”

“They pioneered a theory for our messy emotional lives,” said Jane Hu in the Times this week, recalling the lives they lived. Among the other heros lost, bell hooks, who helped us reimagine limits of collective experience, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the beat hero who beat back censorship, Doris Diether, who fought with Jane Jacobs to beat off Robert Moses, Stanley Aronowitz, who taught me the dialectical interplay between work and play, and Penelope Smith, who made a quilt, reminding me about the sounds of the birds in the morning - they were many.

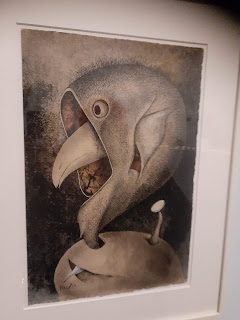

I thought about them walking up Fifth Avenue, past the loominous trees, through the Met, taking in my old friends, Bastien-Lepage’a Joan of Arc, Klimpt’s Mada and Serena, Picasso’s The Actor. I fall in love with art again every time I walk into the Met. Part of the pleasure is watching others do the same. Looking at the pouting Greek and Roman buttocks, the sculpture and paintings on second floor, I’m always filled with excitement. Down we walked to the Surrealism Beyond Border show.

“We are all presidents of dada,” wrote Tristan Tzara in the first Dada Manifesto.

Who made Dada?

“Nobody and Everybody,” said Man Ray.

It's a movement that belongs to everyone and no one.

With an abiding sense of the ridiculous, the movement traversed minds and borders.

The first piece I glanced at was Visa without a Planet, by Abdel Kader El-Janabi.

“I am a mostly an absurdist,” said 18 year old Dodi in Los Angeles Ca, earlier in the fall.

“Jazz is my religion. Surrealism is my point of view,” says Ted Joans.

“Somethings strangely familiar…”

“Surrealism is my fight for the total liberation of man….”

It's a way of exploring “alternative orders” undoing what reason has done wrong, looking for the synchronistic uncanny of everyday life, everyday objects, everyday dreams, excavating ideas from subterranean rumblings, ideas we scribble on dream notebooks.

Between desire and experience, we daydream.

Freud did.

“The virtuous man contents himself with dreaming that which the wicked man does in actual life,” says Sigmund Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams, navigating, “the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.”

There is even a playful confession.

“I had thought about cocaine in a kind of day-dream.”

It's a space to re imagine.

“Shuffle the cards of masculine and faminine,” says Claude Cahoon, 1930. “It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me. If it existed in our language, no one would be able to see my thoughts vasclating.”

“May my desires be fulfilled on the fertile soil of your body without shame,” says Joyce Mansour in 1953.

Unwinding false binaries, surrealism ushered in “timebombs of consciousness,” says Wolfgang Paalen.

For Breton, it amounted to a “derangement of senses.”

Poetic narratives, dreams and chance encounters with butterflies and friends, offer a glimpse of

“...a world in which logic plays no role,” said Beck, 1934.

On we walked, taking in the exquisite corpses, connecting sketches, tracing unknown throughlines from Lawrence Ferlinghetti to Penelope Rosemont, oil paintings, old friends and new, a transnational movement open for everyone, unpacking the deranged logic of progress and empire, pointing us to different fertile knowledge.

Walking out of the show, we strolled down 5th Avenue, looking at the trees looming, stretching, sprawling across the sidewalk, into the park.

Art dancing in my mind, I found myself thinking of the year that had passed, out of the isolation of covid into the isolation of covid, to begin and end the year, in between into the world for much of the rest, trips to San Francisco, down to Santa Cruz, and Los Angeles and back up the coast, listening to No Dogs in Space Podcasts, and out to the end of the world past Vaughns in New Orleans with the teenager, crossing the Delaware out to see mom in Princeton, out to Fire Island with the family, to the Rockaways to surf, and back, before we made our way to Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, into the water. The gestures of civil disobedience that brought us to the fronts of bank buildings, to the capital, Albany for healthcare, across 42nd street for vaccine access and South to Washington DC taking busts for voting rights and Build Back Better Bill that fell short by one vote from the Senator from West Virginia. The teenager eventually moved out West for school and the youngster finally attended school in person. And my long standing late book about sustainability finally came out, with majestic book readings in the park, with LA Kauffman, and many, many other friends, each of whom helped welcome an open space for me in this majestic city. Every week it seemed, a new trip opened from Brussels to Los Angeles to Glasgow for the climate meetings, with abundance mingling between business as usual and our collective daydreams, and nightmares. Ida hit us in Brooklyn, water leaking into the roof and basement. Climate change is real. Throughout it all, the city was changing. I explored the Gowanus and Sunset Park, fighting the rezones turning NYC into a shopping zone, and went to City Hall and East River Park to defend the park and read poems with Eileen and company, reveling in the joy of community and friendship. Tim and Mel welcomed me, even as the breath eluded Tim. He always smiled. I love visiting them and look forward to going again.

All summer I read Joy Division memoirs, Debbie Curtis’, Bernard Sumner’s, Stephen Morris' Record, Play, Pause and Fast Forward, tracing the space between punk and poetry and what you do when you lose something, when Ian wrote about suicide and music changed, moving through an almost Hegelian leap from punk to goth to blue mondays, with Ian in the rear window, not unlike beloved Syd Barret before him, riding his bicycle through our memories, even all these years later. They’d all recall Ian who let it slip away:

“Nothing seems real anymore,” Ian Curtis explained before he departed. “Even the flames from the fire seem to beckon to me, drawing me into some great past life buried somewhere deep in my subconscious, if only I could find the key..if only..if only. Ever since my illness, my condition, I've been trying to find some logical way of passing my time, of justifying a means to an end.”

Maybe there is no key?

I kept on reading and reading about this place, reveling in the shifts and turns, looking at what happens to us, to the ways we adapt, and find meaning.

“Your happy place is my depression,” said the youngster as I sat watching Control, the film based on Debbie Curtis’ memoir about living with Ian, listening to Iggy as he departed.

Covid exposed something deep in all of us that we were all trying to make sense of, as it settled into our collective consciousness.

I sat thinking about it, hanging out with Anthony Bourdain, late at night, going to parts unknown, digging through the archives, and reruns.

I had to stop watching Tony by myself.

And then the Anthony Bourdain documentary came out.

Many had a hard time getting out of their seats after the movie.

Tears in their eyes, our eyes, they sat in their seats watching the credits.

For a second there, I had forgotten what was going to happen.

Then the film reminded me.

He traveled the world, but wasn’t ok with whatever was inside.

In the midst of a pandemic, the movies were our travel.

After school ended, we all went to see Fellini's 8+1⁄2, his 1963 surrealist comedy-drama. What a day, we all walked between the East Village and the West, through Washington Square Park, finally grabbing a seat in the old Film Forum, my first movie in a year and a half.

Coming attractions included a preview of Truman and Tennessee, an intimate conversation, a film about the two majestic Southern authors, queer gothic like none other, a friendship that extended through the decades. When shall we meet each other again, Tennessee asks Truman toward the end. In paradise, replies Truman. A few days later Williams departed. Truman was right. It wasn’t long before he followed him.

I guess we look to writers such as this to help us find something, some meaning, some epiphany.

Books of the year included: Sentimental Education, Borges and Me, Twenty Days in Turin, Member of the Wedding, Chelsea Girls, Parisian Lives, Immigration Crossroads, Social Movement Archive and Simone de Beauvoir by Deirdre Blair. All spring, we slogged through the Magic Mountain, trying to make sense of our current malody, reflecting on the ways tuberculosis impacted culture.

“It is love, not reason, that is stronger than death,” says Mann.

“Laughter is a sunbeam of the soul.”

We isolate and separate. Thomas Mann writes:

I cannot help but remember Stanley reading Dr Faustus, sitting in his bed the last time I saw him last winter. It's his magnum opus, said Stanley, talking with me about Borges and Blazac.

I think about sitting with Penelope looking at the birds in the winter that last meeting in October before she shuffled off a few weeks later.

When the teenager moved out, I put my faith in the city and it opened up something wonderful, offering me music and art and community and poems and comrades to meet and students to teach and a late night meeting when we stayed up past closing time and I woke up with a scratchy throat.

Back in town for the holidays, the teenager tested positive and then I did.

Covid came to visit and on and on and on, grasping us, taking my breath, robbing me of my strength and then letting me go. For a few days there, I felt like I was losing something. But it was ok.

As Montaigne wrote about getting sick:

“I was much more terrified of illness when I was well than when I felt ill. Being healthy leads me to get the other state quite out of proportion, so that I mentally increase all its discomforts and imagine them heavier than they prove to be when I have to bear them.”

It's a physical ailment, as well as a mental one.

It's not clear which is more impactful.

Each Tuesday, we met at Barbes to catch up.

On other days, we walked through the Gowanus, watching the construction crews arrive, exploring remaining secret places with the kids, talking about music, riding to rallies for a #NewDeal4CUNY, aspiring, sharing poetry together, connecting, beating back alienating social relations, thinking about books and another year gone by.

“RIP: bell hooks, Sarah Weddington, Colin Robinson, Dr Joseph Sonnabend, Carmen Vasquez, Alix Dobkin, Louise Fishman, Lauren Berlant, Ari Gold, Greg Tate, Elisabeth Rich, Madeline Davis, Richard McCann, Deb Price, Charles Lum, Maria Perez,” Sarah Schulman posted.