Walking and thinking, walking and not thinking, walking and being, walking and connecting with everyone, walking completely by myself and connecting with the trees, celebrating with everyone, being completely alone, these were part of the countless adventures the last few days of the Camino last summer. This will be my last entry on the matter, at least for this trip.

|

| Sites from the Camino summer 2015. |

|

| Scenes from Caroline's camera, snaps along the way. |

When I last wrote we were staying in Barbadelo. Everyone was up most of the night.

But the next day was still coming. We had three days to to go as we started day 19th, walking from Barbadelo to Gonzar, 108 k to get to Santiago.

At breakfast at 6:30 AM.I apologize to the Italians They were munched by the bed bugs too.

There are three or four days to go on the trail,

probably three. Everyone seems to have

lost our minds.

More and more people are on the trail. The day hikers show up on their buses. People

walk without backpacks. The guidebook notes that passing judgment serves no one. Still, I simmer when I see people in clean

clothes with fresh pilgrim t shirts and sneakers. They seem so perky and fresh,

no blisters. But who am I to say? Who am I?

Its not a philosophical question.

Its practical. By this point, its

hard to know. But my thoughts are my comfort.

The trees seem to know who I am.

I greet them, seeing faces in each.

They seem to greet me back.

Or maybe it’s the man at the store who asks if I’d

like my pilgrim book stamped? Starting

in Sarria, we have to get them stamped twice a day. He offers us stamps and asks if we’re

interested in souvenirs? Everything can

be commodified, including the Camino. At

this point, it wouldn’t be a social movement if that wasn’t the case. I can’t name a movement where it hasn’t

happened. Commodify your dissent.

I don’t even mind.

The route is still striking. When

I see the day hikers still aching along the day, I’m glad to know I’m not the

only one. My blisters have healed. The skin hardened on my feet along with the

second skin bandaids which are the work of genius.

So we walk. I

greet my friends from South Korea, strong as ever after hiking all the

way. Walking as a group, greeting

everyone, speaking in three four languages as they make their way.

My trusty walking stick has just about disappeared

several times along the road, reminding me to slow down and walk backward to

get her over and over again.

“I really like that stick,” several say. A man with a beard from is standing outside

the bar. We start chatting. A teacher from McGill University in Montreal,

he walks with his daughter. Walking and

cross country skiing are his main occupations when not teaching or doing

research. He sits with everyone, is

friends with everyone.

“We are all carriers of ideas,” he explains,

chatting about novels and stories. We talk about Cervantez and the Camino and

the lessons of the road.

“We wash our clothes and let the sun dry them,” he

reflects. “It’s a lesson we can take through our lives.”

We talk about Percival. He locates this story in the Alchemist. I find it in Fournier’s the Wanderer. The grail is in all of us, if only we can see

it in our own communities, inside us.

“You have got to be able to let go of whatever is

too heavy and let the road off you what you need,” he follows.

“Sometimes when I am in line for a shower and I

finally get there, I am so relieved. I

think of home and how lovely it is just to have a shower when I want it. The trail is always reminding me of how

lovely home is, just how lovely it is to be home.”

We chat then stop seamlessly. We’ve all seen each other for days now.

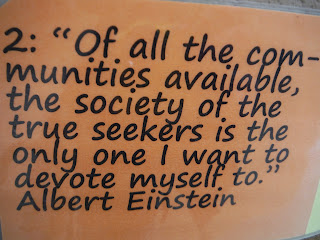

Walking forward with number two, we look at painted

shells decorated outside a bodega along the road. For a long time, Pilgrims were given a shell

from a scallop and a manuscript when they arrived in Santiago. They hung the shells on their packs. Today they are everywhere, a symbol of the Camino.

Many suggest they seem to represent the changed life we all experience as we

walk. Walking home we would be different. The shells seem to look like a hand,

symbolizing good works, the spirit of the way, which compels us to walk, share,

conserve, care, talk, and support this roving city of friends. This metropolis of ideas and people, stories

and struggles compels us to move forward, reminding us we can all make it with

the support of an essential other, be it a walking stick, a friend, family

member, or even a tree branch stretching out into the road to greet us and

remind of the beauty of the world. They all remind us to keep moving forward,

offering us shade and support, or even a place for a picnic.

Standing there, we run into Antonio and his son,

Triston, who interviews me about the road. I talk about Percival, but wish I

had said more. After they leave, I wish I

had a second chance to talk with him.

Some kids

from Texans come to chat. One is from Lubbock;

the other from Spain. She is bringing

her buddies along for the trail. Every day, we meet more people with more

stories.

Another woman from France tells me her feet are

aching. She has blisters. I ask where she started.

“Sarria,” she explains. Don’t judge Ben, I think to

myself and walk further ahead. That’s ten k ago I think to myself. Everyone finds their own struggles along the

way. The yellow arrow points forward. I

go find the next one and walk.

We walk and walk and walk and walk.

The last ten k of the day are always the hardest.

Crossing the bridge into Portomarin, we stop for

lunch and hang out a bit.

“Does anyone know where the Camino is?” asks an

American in a gruff voice, not even trying to ask in bad Spanish.

I point it out to him. And we walk up a hill winding

hill and out of town.

“This is shit,” declares number two, throwing down

her walking stick. “Walking to another town, another shit town. This is shit.”

“You sound world weary.”

“What’s that?”

“Tired of the world.”

“Well I am.”

I walk behind to get her stick, talking with two

younger women from Amsterdam, who are just behind us. They offer a little

support and we keep walking.

Gradually I stumble into the American I’d seen the

café.

We strike a conversation as we walk the last ten

k. Unemployed and seemingly unable to

complete his studies, he is walking. Romance seems iffy, he is on again off

again with a women in Holland. His bank

has cut him off, so he walks. He got tendinitis and stopped for a day in

Sarria to get some medical support. His bank card turned off, he is broke and

walking 40 k a day, looping the Camino, back and forth.

“Have you walked with anyone?” I ask.

“I left a group of friends, women, we were walking

with. We hiked from Estella to Los Arcos.

I got there and I was alone. I

walked into the Cathedral, but my head in my hands and started to cry. Never get talked into walking with an

ambitious Spanish man.”

I could see the despair on his face. The pain, the dead end stories of the Camino

are many. Yet, his is pointing to

something.

“Its great what you are doing. My parents never spent any time with me,

never. I always regretted that. You are spending

real time with you family.”

And so we walked, talking about the US, our

inability to learn from our history, the confederate flag debates, lack of gun

laws, racism, and US cultural amnesia. One looks at the walls, the bricks and

mortar of these old villages, and it reminds observers of the history of Spain,

of El Cid, St James, and their mythic struggles, as well as those very real

battles against Franco and fascism, not so long ago.

In the middle of nowhere, looking at an empty ghost town and a bar full of hikers, I looked at my text and Caroline had already gotten to Casa Garcia, the albergue where we were staying.

“Where are you?” Caroline asked in a text.

Matt and I have been talking.

“I gotta get going,” I explain.

“Good luck with finding your family,” Matt said

goodbye. I walked around. A young woman is smiling. She points the other way. In between small village roads, stray cats,

and clothes lines, I saw Casa Garcia.

Walking in Caroline was smiling, drinking a beer in

a cowboy bar. Our friends Antonio and

Triston, the Irish, our friends from San Diego, most everyone we knew were

there, sitting.

“This is lovely,” noted Caroline, smiling. It was our 14th wedding anniversary. Last year we’d celebrated with my brother and

his wife in Bordeaux. The year before in

Coney Island with our neighbors, before decade of anniversary dinners at the River

Café in beloved Brooklyn. With a room

full of our friends from the hike, this would be the best one yet.

That night, we celebrated our anniversary dinner. Even

before we sat down for our 6:30 dinner, number two, our youngest, had been

chatting with everyone there for hours. Number one sat quietly, joking, quoting

her favorite comedian, Miranda Sings.

“Donde esta Taco Bell?”

As we eat and drank cava, more and more friends

arrived from the road, people we’d been hiking with from Spain, Holland,

Ireland, Germany, Italy, France, Mexico, Philadelphia, by way of Spain, the

four women traveling together.

We share stories and band aids, second skin packs

and advice from the road.

Antonio and his son sit chatting away, talking about

their lives in Spain and the US, their film project, etc.

Caroline and Antonio commiserate about bed bugs. He had contracted them at Villafranca del

Bierzo at the municipal, where our friend from San Diego fled. She’d heard terrible things about that albergue. But did not remember the name. Then when she

was in the shower, she saw the sign and realized where she was. She got out, grabbed her stuff, and

fled. Antonio and his son stayed, waking

up later that night with bites all over his body. He’d later have to go to the hospital and

take a few days off the trail.

The Camino operates through word of mouth. We hear about people along the trail, “the

American family traveling together”, “The Swedes with their toddler,”“the

father and son”, “the bad albergue in Villafranca del Bierzo.” Word travels through the trail. We’d heard

about Antonio getting sick before he told us.

The problem is that not everyone is in on the story. We don’t all hear the same stories about the

same albergues. There has to be specific.

“You need to shame them,” noted Antonio, who was

going to write to the city governments throughout the trail to lodge complains

about the bugs when he got back home.

Antonio talked about the last time he hiked the

trail three decades ago, when people invited the pilgrims into their homes.

“That is gone,” he lamented, noting the trail has changed.

“But for all our difficulties, can you imagine what the pilgrims went through

hundreds of years ago, walking for days while eating berries, or maybe a bowl

of soup? They could only dream of what

we have here.”

The son asked to do another interview and we said

yes if we could ask his dad about the years under Franco. His expression

changed from animated to cold. There was a pause. “I really can’t… My grandfather was a

Republican, which meant he wanted more schools, education, and a modern

democracy. And he disappeared.” His blank expression said it all. “I was four

when he died.” I did not ask any more.

So we share global stories on the Camino. The father and son, parents and kids. We all hope for something real and authentic,

a way to learn. The son planned to walk

all the way to Finnisterre. Many plan to do so.

Other plan to stop in Santiago.

“But look at her.

She’s made it the whole way,” noted Antonio, referring to our nine year

old. “Many of the day hikers are

exhausted after an afternoon on the trail.

Yet, she’s made the whole way.”

Everyone was full of compliments for the two

American girls, making it through the often challenging terrain. There are only

a few other kids on the trail. Yet,

these kids have walked the whole way.

“You have no idea how much this trip is going to

leave an impression your kids,” noted my friend Monica.

“You guys could learn another language or two if

tried now,” noted Antonio. I hope the

girls do. I really do.

Yes, the walk was tiring, but we had places to go at

night, food, rest spots, unlike the Armenians, walked to death by the Turks, a

hundred years ago.

“Who remembers the Armenians?” wondered Hitler year

later, as he laid out his plans.

We were lucky to be able to be there, drinking

Spanish wine, talking with friends, still popping in from the road, looking for

a place to stay or a familiar face to talk with, still looking for something

real.

Mostly, there are people of my generation and

younger, hiking, experiencing a rite of passage of the Camino together, looking

for an encounter with friends, history, and a way to beat back alienation

together.

Just as Cervantez influenced Faulkner and Marquez

and Borges, winding a magic realist

narrative through time, so do the stories we share here.

“I could show you a thousand ways that we are still

grappling with Franco here,” noted Antonio.

We are all battling cultural amnesia.

Its easier to forget than to grapple with the lessons of such

moments. The US continues to hide away

from its racism, while pointing fingers elsewhere. In Spain, the scars of the civil war can

still be seen on the faces of the elders.

If there is one thing about the trail, I have grown

to really resent is nationalism.

Earlier in the day, a woman was offering coffee and

bananas to everyone on the trail. “What

language do you speak?” she asked in English and Spanish.

“Catalan,” noted one of the day hikers, with

contempt on his tongue. The nationalists

of the world bore me.

So we talked and talked, made plans for places to

stay, called hotels, and made arrangements to meet up in Mato-Casanova the next

day, another thirty k down the trail.

“You had better know where you are going,” noted

Antonio. He was right. We would not see him again.

I would see only a few of them again, after that

glorious evening. We’d hike for three more days, before one last reunion in

Santiago.

Day 20th Gonzar to Mato Casanova

The roots of trees seem to wind their way through

the age old walls along the trail, the dialectic between nature and the modern,

between the primordial and the conscious brain, planning and moving forward.

We slept well that night. And got up early. Number Two was angry and tired.

The pain of the trip lingered in her bones.

I had heard news about on old friend from work, who

had died after years of struggle against HIV/AIDS.

The emotions of the road are so many.

Sadness and grief and the people Cary F, an old

classmate, Dad, Tom, our uncle and brother and law, and today Laverne, who I

think about on the trail, as I wrote

on facebook.

I've spend the last month walking the Camino de

Santiago in spain. We walked 25 miles today. In a few days, we get to Santiago

after another 30 k. we've walked three hundred miles together. Throughout the

walk, we place stones for those lost to our lives. I've placed them for uncle

tom, carrie f, an old classmate, and for my dad. With 78 k to get to Santiago, I placed one for Laverne. I’ve known her since 2001. She was someone I

knew at citywide back in the day. She worked like crazy to stop the epidemic. And

she always said hi through the years, even when others did not. I last saw her in June at the campaign to end

the epidemic event at City Hall. And she

said hi. I am sorry we were not able to

do more to stop the epidemic, Lavern. I

am sorry we were not able to do more to stop the epidemic in your

lifetime. But god knows you tried. Thanks

for always saying hi.

The Camino gives us a place to remember and feel

people we’ve known, to put that stone on a pile of stones, recalling the

departed and walk in their memory, walk for them, with them, forever together

through time. all the actions of the campaign to end aids.

she also said hi to me demo after demo after I left citywide and not everyone

said hello. Cameron and laverne always said hello. I saw her in June at the end

aids press conference at city hall. she said hello as she always did. thanks

for being my friend Laverne. i'm sorry we were not able to end the epidemic in

your lifetime here. but god knows we tried and you tried. god knows you tried

and you cared. thanks for that laverne. I can't imagine going to a vocal action

and not seeing you. thanks for always saying hi.

It was a 39 k hike, exhausting. When we arrived at Mato Casanova, none of our

close friends were there. We stumbled

into a few of the hikers from Holland.

But that was it. A big empty

place in the forest, we ate and passed out.

Day 21 Mato-Casanova to Salceda

We left the hotel in the pitch black, walking our of

our room at 5:55 am. It would be our

longest day on the trail.

Number two was terrified to walk into the woods in

the pitch black. “We can’t to it,” she

said over and over, visibly fearful. We

held her hand and walked with our cell phone lights in hand, looking for yellow

signs, making sure to stay on the path. Dogs

barked in the distance. We walked for a

half hour before a peep of sunlight began to show itself. And gradually number two began to see she

could make it. The sun began to rise,

light pouring through the trees.

Trees everywhere.

“Its like walking through a medieval village after

the plague,” noted Caroline, passing Furelos, a town with a population of 135.

Seemed more like the road warrior to me, quiet and

desolate city, graffiti everywhere, but empty except for a few cats who walk with

us.

We wouldn’t find anywhere to eat for another hour. And finally, 7 K out we get a cup of coffee at 7:45 am. “It feels

like Ireland. I feel good,” she

continued. It was the second to last day

on the trail. We were going to make it.

Yet, the marks from the begs have became round and

red, settling into my skin, reminders of pain and history.

By 10:50 am, we’ve covered 14 k. Only 16 or 17 more to go. And then after

tomorrow the adventure is over. We feel

better than ever about home after all these adventures. That’s

the biggest lesson of the Camino, that home is good. Yet, going home is different. We are different.

Number one is walking stoically, number two cursing

like a sailor, and mom is walking like she is dead. But she is doing it. We all are.

“It’s a swell family vacation,” number one remarks

as we walk. Humor has kept her going,

even keep the whole walk.

Yet, it really is, even if we just meander. Each town, break for coffee, soup, person,

tree, bird chirping, or small chat with a fellow Pilgrim means so much to

me. Even the challenges are something we

can love, we can grow from. It’s a trip

we will talk about forever.

We take a break under a tree, sitting for a bit.

“Its not going to happen every year that we do

this,” notes Caroline, honoring the childhood of the girls and our time

together.

At some point, I walk ahead to get the room in

Salceda. Its feels like all afternoon

that I walk through the trees, their animated faces looking at me, as they take

shape through the branches, smiling, honoring age and time.

I think of my Dad and walk. This is my meditation and people around me. There are things I wish I had done. I wish I had seen him one more time and

really said goodbye. When he could barely talk, I could have driven to

Texas. But I didn’t. So I live with that and walk. And honor the time with my gang, with my kids

as they grow up, of time passing, and our lives changing.

I get to the Pousada de Salceda by 5:45, securing a

great room for us all. They have a foot

path and a great restaurant and outdoor area where everyone hangs out in this

200 year old albergue, renovated only a couple of years ago.

They are sweet, offering to take all our laundry and

wash it, for only a few euros. They want to be sure we get cleaned so we sleep

well, with no bed bugs around. It’s a

relief someone takes this seriously.

They want to know the albergues where we got the bugs, laughing I tell

them.

The girls are still hiking. They’ll stop for a bite before making it

in. They feel great, noting they could

have walked further than the 38 k. They could have kept going. Now that we are about done, everyone is

completely in shape for the hike.

By dinner time, my buddy from Italy is sitting

having a glass of wine. We eat together,

laughing about the road.

“Hola, hola, hola,”

she jokes. “Everyone asks about

all the important things we are thinking, but I really am just thinking about

all the miles to walk.”

So we chat about where she lived and where we’ve been.

“The last two nights, no one, everyone disappeared,”

she noted. “I didn’t run into anyone.”

It was just two nights prior that we all were

together at Casa Garcia.

The dinner was quiet. Our other lives are coming again. She works for an NGO. I’m a teaching and

organizer and social worker. What will

my next be, probably to write up this story and make sense of all we saw.

As we’ve hiked, I’ve thought about it, over and

over. There are feelings of hope about

the lessons and loss. We grieve for a

lot on the trail, including for the trees destroyed, the natural environment,

and landscape lost and then rediscovered as we walk. Over and over again, we go through these

cycles of loss and separation, followed by connection, as reification is replaced by remembering.

The feelings of hope and lessons for a more

sustainable future are many. Lessons of the trail are many

A few include:

A hope for less nationalism

More talking and sharing

Less owning, more walking together

Collective processes

Don’t pet stray cats

Unplug cause the internet does not really work here

Plus its over rated

And trust the process, so walk it out even when

tired or grumpy

Bring mosquito repellant to battle those little

fuckers

Remember bugs have changed history

Enjoy the adventure, just as Don Quixote might have

Chase windmills and free your mind

Pick up garbage

Look out for bugs

We need less than can possibly imagine

Let the sun dry your clothes

Be open to people, transnational conversations,

communication

Greet one another with kindness

Leave no trace

Use your feet more

Ride bikes

more

Travel with your feet

Let them guide you

Battling xenophobia

Day 22 August 31, Salceda to Santiago

It’s a good feeling to walk each day, the best

feeling to walk with friends and family.

I greet the eucalyptus trees and forest as we walk for our last day.

Its complicated to find our way. But we walk all day. I leave my old walking stick behind, walking

off the trail for a bit when I get it back.

“I love New York,” a women at the coffee shop

comments.

My friends from Korea are there. We greet each other and take a few

photos. One college kid knocks over his

friend’s coffee. I owe you one, he

comments. We are all bulls in China

shops, us Americans, even as we aspire to be travelers with beards and beatitues. But a little humility goes a long way.

“On the Camino, we are all equal,” notes one of my

many friends from Holland, who with ate with during that big meal at Casa

Garcia. “We all go through our phases,

bugs, pain, blisters, fatigue, and continuing.

Before the trip, her knee was a wreck. She had surgery on it. And hoped it would survive. She plays music, drums with that knee so she

needs it.

And today she is walking with it.

“I am no longer afraid of the forest,” notes number

two, who walks with me throughout the day.

We talk about “Exile on Main street.”

She greets a friend and we walk.

We are only five k away from Santiago.

A big huge grin and feeling of relief comes across

number two's face when she sees the Cathedral in the distance.

She sits in the park, looking at the cathedral. We roll down the hill in celebration.

But the final five k are hard as we walk through

town. We wander through the angling busy

streets of the city. Its hard to even

find the yellow lines. But we walk,

getting closer and closer.

“Ben,” I hear someone scream. Its our funny New

Yorkers, who’ve arrived a couple of hours ago.

They are sitting in a Café Flor, having a drink.

“This is it, your epic arrival! Bravo to you!” they greet us. We’ve now see them four times

on the trail in three different towns, O Cebreiro, Sarria, and Santiago.

We plan for dinner and keep walking. We’ll meet them at eight pm.

Number two and I walk and walk, through the streets

of the medieval city, through the plazas, looking for the Cathedral.

Arriving, I felt a deep feeling of success and

completion, awe finally seeing that Cathedral, giving number two a hug. Later, we celebrate with the funny new Yorkers at café le flor, toasting

the completion of the journey with them, over cerveza and nachos.

The next day, we go for our credential at the

cathedral.

“What did you think of the Camino?” the man giving

the credentials asked number two.

“Some of it was hard; some of it was fun” she

confessed.

“She’s one of the youngest kids I have ever seen

complete the route,” he later explained to me.

We saw our Swedish, Dutch and German friends in the

line, greeting the professor from Canada.

“Its Benjamin and his family.”

Many had hiked since 4 am, walking with the full

moon.

|

| One of the youngest to receive the compostella. |

|

| We’d all become a part of a roving city of friends along the way. |

|

| My younger brother Will had hiked from Portugal to Santiago with his family. He's the one who got us on this crazy trip in the first place. |

We all see each other at mass. I am more ambivalent than ever about the church. The sins of the inquisitions, crusades, condemnation of gay people, subjugation of women, etc. these can’t be easily forgotten. A part of the Camino is reckoning back to an intolerant Europe, of Christianity, and history of Spain that sought to vanquish Moores and by the extension the other.

Throughout Santiago, boy and girl scouts walk in

“brown shirts” no less, seeming to lack an awareness of the symbolism on their

backs, connecting them with a fascist past which not long ago cast a shadow

over this country.

A group of tourists walk in, very young, with “pro

life” stickers on their shirts. I am

disgusted, recalling the church’s opposition to women’s choices or reproductive

autonomy. Poverty grows without family

planning, yet these people were these shirts.

Its scary. The scandal which rocked the church in recent years seems

obfuscated within this obedience.

By communion when we are reminded only good Catholics

can take part, so we choose to leave.

Number two and I go see St James’ remains, a box, which they say hold

his bones. Whether its there or not does not seem to be the point. The lessons of the hike are many, if even

muddied by history. There is of course, a counter narrative, which opens to a

cross-border solidarity, self organization, even anarchism, open to gestures of

care among the movements of hikers taking part.

Many of us harken to a world in which we consume less, seek to share,

build solidarity among friends, rejecting monoculture and mass transit, in

favor of people powered machines and feet.

“The pilgrim’s body is not only a conduit of

knowledge,” notes Nancy Louise Frey (1998, 218-20,222, “ but also a medium of

communication, a means to connect and make contact with others, the self, the

past and the future, nature. The body

can also be used as an agent of social

change (“cause pilgrims”), as a way to protest the fast paced, disheartening

aspects of modern society, and as a way to peacefully ask for change. Pilgrims

are noticed, and on some level many want to be noticed: perhaps they are making

a cry for help, a show of grief, a testament of faith, a plea against

resignation and persona and social stagnation, a statement about an alternative

way of living, or a public protest. In

this way pilgrims not only pray with their feel but also speak with or through

their feet or their bicycles.” The pilgrimage

is this a story of friends, shared connections and endeavors, as well as

“competing discourses” between our lives, experiences and perceptions, with

those of others whose presence we feel, even if they are no longer on the

trail. But they once were and maybe will

be again. (Frey, p.215-222).

But we are all a part of this body, a bigger body

than ourselves, joining this pilgrimage of deeds, connecting our own lives with

so many otherswe’ve met along the trail.

My brother comes to join us at the Cathedral. His family has hiked since Porto in

Portugal. We’ve all grown walking and

seeing the world.

He brought us to the Camino and for that we are all

grateful. Our father loved that Will walked it, reading his story of the

journey with pride. He lived will’s memoir of the trip. Our connection in Santiago marks a new stage

in our lives together. The two daughters

knit each others hair in mass. And then

we share a long afternoon meal, a meal for the ages, toasting with delicious

vinto tinto and gaseosa.

Taking the bus away, its sad to say goodbye to

Spain, this land of ghosts that has given us so much.

Its something none of us are going to be quick to

say goodbye to, those country vistas, the after dinner strolls, the long

afternoons, the challenges we walk through lasting forever in our minds, etched

their for eternity. Those images we saw, those vistas of the country hamlets are

now firmly etched in our souls and dreams, to repeated and remembered again and

again in the lore of our lives. The way is always a place we can go, connecting

our cities and stories with a much larger trail.

The other day, number two and i were on the subway in the concrete junble of New York City.

Number two pointed to a yellow sign right below the subway tracks. The way leads us from there and back again over and over again. We are all Parcival, finding ourselves along the way here.

The other day, number two and i were on the subway in the concrete junble of New York City.

Number two pointed to a yellow sign right below the subway tracks. The way leads us from there and back again over and over again. We are all Parcival, finding ourselves along the way here.

Sources

Brierley, John.

2013. A Pilgrim’s Guide to the

Camino de Santiago. Camino Guides, Forres Scotland.

Dintaman, Anna and Landis, David. 2013. Hiking

the Camino de Santiago. Village Press: Harleysville Pa.

Frey, Nancy Louise. 1998. Pilgrim

Tales: On and Off the Road to Santiago: Journeys Along an Ancient Way in Modern

Spain. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kerreling, Hape. 2001. I’m off Then: Losing and Finding Myself on the Camino de Santiago.

New York: Free Press

Ludwig, Ken. 2013.

How to Teach Shakespeare to Your

Kids. Broadway Books, NY

Tremlett, Giles. 2008. Ghosts

of Spain: Travels Through Spain and Its Silent Past. Walker Press

No comments:

Post a Comment