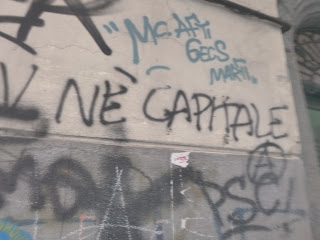

I didn’t really know what to think of Naples. I’d been here before only briefly, never spending much time in Southern Italy. When I was here a quarter century ago everyone warned that it was a dangerous mess. But it was time to leave Rome. The summer months, the crowds are hard there. We love it, but it was time to go. I was immediately surprised in Naples. The streets felt thinner, cobble stoned, like a dream, reflecting Spanish, Bourbon, and Roman influences. The cabbie could not find our hotel. So we used our GPS lead us through a twisting journey. The cobble stone streets just got smaller. Right in front of a small piazza filled with graffiti, down the street from a gay bar. Everywhere we walked, graffiti and people. We started reading the graffiti. “Not free till everyone is free,” read one, “Tourists go home this is class war,” declared another, communist, fascist, and anarchist logos covering each other on each street corner. A woman was scolding a motorcyclist, college students everywhere. The streets were vibrant with energy. A woman waved from a squat declaring housing for all.

We ate at a small mom and pop restaurant. The waiter brought us round after round of antipasti, vino de casa, and we ate. Street singers came to sing opera songs, sad and aching songs. One, the Neapolitan Song, "Funiculì, Funiculà" by Luigi Denza with lyrics by Peppino Turco. was written in 1880 in dedication to the fernicular cable car going up to Mt Vesuvius, just in sight of Naples.

I climbed up high this evening, oh, Nanetta,

Do you know where? Do you know where?

Where your ungrateful heart no longer pains me

With teasing wiles! With teasing wiles!

Where fire burns, but if you run away,

It lets you be, it lets you be!

It doesn't follow after nor torment you

Just with a look, just with a look.

(Chorus)

Let's go, let's go! To the top we'll go!

Let's go, let's go! To the top we'll go!

Funiculi, funicula, funiculi, funicula!

To the top we'll go, funiculi, funicula!

The car has climbed up high, see, climbed up high now,

Right to the top! Right to the top!

It went, and turned around, and came back down,

And now it's stopped! And now it's stopped!

The top is turning round, and round, and round,

Around yourself! Around yourself!

My heart is singing that on such a day

We should be wed! We should be wed!

(Chorus)

Let's go, let's go! To the top we'll go!

Let's go, let's go! To the top we'll go!

Funiculi, funicula, funiculi, funicula!

To the top we'll go, funiculi, funicula!

He sang loud, powerful notes, filling the evening.

As we finished, our friends Greg and Molly from NYC dropped by. They’ve been in Paris all year. I saw them in December for the COP Climate Talks. We walked through the same streets.

The next day, we made our way to Pompeii. The streets of Naples are so full of vitality. It’s a joy to walk here. At Pompeii, our guide explains most of the buildings were destroyed here during the eruption of Mt Vesuvius on the 24th of August 79 AD.

“But the exact date is not clear,” he explains.

“Well, it depends on which calendar you are using, Julius’ new one or the old one,” jokes Caroline.

17 years after the 62 quake jolted the city, the world started changing around Pompeii.

According to the ancient history encyclopedia:

“It was then, in high summer, that strange things began to occur. Fish floated dead in the Sarno, springs and wells inexplicably dried up and vines on the slopes of Vesuvius mysteriously wilted and died. Seismic activity, although not strong, increased dramatically in frequency. Something was clearly not right. Strangely, although some people left the town, the majority of the population seemed to still not be too worried about the events that were unfolding but little did they know that they were about to face an apocalypse.”

We spent all day exploring the ruins of this post-apocalyptic mess, where people were engulfed, covered in ash. Some left early. Others thought it was going to pass. By the time they chose to run, rocks and ash were pouring around them. Molding of bodies shows people dying as poison gas and piles of ash enveloped them, crushing their ceilings. Many thought it was a punishment from the gods. The mountain named for the ‘wine of Venus’ would erupt for a week, changing history.

For centuries, people thought Pompeii was a place to die. No one went there. It was not until the mid-17th century when workers began to bump into fragments of Pompeii and Herculaneum that they started going back.

We explored for hours, looking at old frescos and moldings, images of a life, eros, death, and a crumbled civilization. A theater stands empty. Images of sex on the old frescos, with a group of people watching.

“A momentary embrace,” noted a couple of British tourists.

The place is starkly beautiful.

Inevitably, we talk about various theories of the fall of Rome.

“The Romans would tolerate any religion,” noted our amiable tour guide, “except the Christians. In a world in which 40% were slaves, the other 40 were poor, and 20% owned everything, his message that everyone was equal was striking and revolutionary. So Christians hid. But their religion was the beginning of the end of Rome.”

Today, Vesuvius looks beautiful and ominous, exquisite in the clouds in the distance.

“Never has such a tragedy given so much happiness” our tour guide quoted Goethe about the scene. I couldn’t find the quote anywhere, but the sentiment seems to resonate through the ages.

Gradually, we make our way back, enjoying an Aperol Spritz in the afternoon, taking in more of the graffiti, looking out at the city.

“Housing for everyone,” declares a sign hanging from a squat.

The promise of Naples is everywhere, so is the violence, the motorcycles, the mob hits, deaths reported in the papers, the lovely food, people sitting out in the streets. A woman waves from her squat. We want to play and explore in the streets for hours, until everyone collapses.

We reflect on the graffiti and the stories we heard throughout the day, about tragedy and the history of Naples, where the Romans, Normans, French, Spanish, and eventually the country of Italy claimed and molded their streets and the very geography of their city.

Saturday, we explored the catacombs and unpack a few more of the layers. After a lovely breakfast together we wandered out through the heart of Naples’ historic district to explore the caves, architecture, and the culture of the dead throughout Il Rione Sanita, the Rione District.

We never quite found the catacombs. What we did find were majestic streets full of graffiti. Greg pointed out one anarchist sign covered by the communist symbol and still another symbol we could not recognize. Sadly, we also saw a handful of swastikas.

But mostly, we were in awe of the people and the aesthetics of these 18th century streets, part Spanish, part Neapolitan.

When I was last in Italy, a quarter century ago, all the talk was about the Lombard League proposing cutting Italy in two. While the south is fabled to rarely pay taxes, the public infrastructure seems neglected.

Walking a woman thanked us for coming to visit her city.

Another man smiled and asked to try on my glasses, laughing.

Later, we all ran to the beach, where we swam all afternoon, a bombed out building on one end of the beach, Vesuvius in the distance.

There is an undeniably romantic feeling of swimming within the shadow of Vesuvius, ever ready to explode again.

We explore and explore. Sunday we head out to make our way through the Napoli Sotterranea, the city’s 2500-year-old underground. The Romans turned many of the caves of the region into an aqueduct system of tunnels and cisterns that stayed active until the end of the empire. They gradually became a garbage dump, closed in the 20th century because of Cholera. Only with the bombings during WWII did the city open them up again, using them as air raid shelters where women, children, the old and feeble often stayed for days.

Gradually we make our way through these cold tunnels, connecting caves, navigating between the streets and an underground theater, a woman discovered when she was trying to create a wine cellar in her basement.

We eat some lunch and keep exploring through the relics of the Naples Archeological Museum.

“This is one of the most important collections of statues in Europe,” explains the tour guide.

“There are no replicas, but many copies,” he explained.

“The Romans copied the Greeks and created a renaissance, Michelangelo copied the Greeks. Good artists borrow, great artists steal,” I followed, echoing my old art history teacher.

He shows mosaics and frescos from Pompeii. “The frescos are an expression of light and color and status. Vesuvius destroyed a high point in civilization. We don’t know whose house this was, but he was obviously very rich” he explained, pointing to a majestic fresco of Alexander the Great. “These highly decorated houses were a peak of empire.”

Some of the frescos involve eros, many others Thanatos. The fresco of a skeleton with a bottle of wine was a reminder that we die. Images of penises are everywhere. “They are talismans to guard against evil spirits,” explains our guide, “not signs of death.”

He points at a fresco of a skull on a wheel. “We are all on the same level at death,” he continues.

He points to Jupiter transformed and then to an image of a Hermaphrodite, who according to legend was the offspring of Aphrodite and Hermes. “The Platonic ideal,” he explains, referring to the Symposium. We are all struggling to unify our male and female selves.

I look out the window and see a pile of columns on dirt in the back of the museum yard.

“Take a look at this,” I point out. “Any other museum in the world, this would be their prize. Here it is in back among the other ruins and trash.”

“Benjamin come here,” smiles the guide, pointing to the collection of porn frescos and murals and sculptures, images any number of sex acts, Venus in the shell, a marble sculpture of Pan and the Goat. “Look, it looks like they are making love.”

There are frescos of the menu of sex acts available in Pompeii, in one in Latin the words, “Pull slowly.”

Several offer images of a mix of superstition – the penis – and religion – the gods.

The message written in bronze in front of a large phallus presumably outside someone’s house, “Here lives happiness.”

“I know you could be here for hours Benjamin, but its time for the next room,” the guide smiles.

He shows us a mural of the Temple of the Diver, descending to death, moving from one condition, living in air, into water.

We wander out to make our flight to Palermo. Sitting in the piazza outside our hotel is a plate with a sign for Benedetto Croce, the Italian Sociologist who spent his life here. At first he railed against the Risorgimento and then against Fascism. He was seen as a moral leader. According to Enclopedia Britanica,

The image of the Italian which animated [his] work was severe and beautiful. Creative effort, a passion for freedom united with a profound sense of civic duty, a lifestyle purged of all rhetoric and sentimental romanticism, unambiguous norms of public and private truth, a sense of history united with an obligation to the future, unceasing but constructive self-criticism—those were its elements. That image strongly reflected the personal ideal Croce had gradually formed for himself. But history was preparing to put that ideal to the test.

Its been a joy to visit Naples. Sicily is next. But for now. Naples was a delight, just like the song.

No comments:

Post a Comment