|

| lucky to be here |

Yesterday at Judson, our 14-year-old read a poem at Kids day at Judson memorial church, where she has gone with me for a decade.

“Lucky” by Kirsten Dierking

All this time,

the life you were

supposed to live

has been rising all around you

like the walls of a house

designed with warm

harmonious lines.

As if you had actually

planned it that way.

As if you had

stacked up bricks

at random,

and built by mistake

a lucky star.

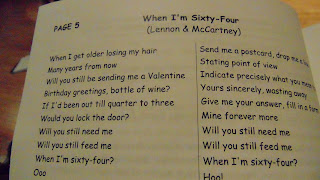

Andy, of Judson Sunday School, wanted her to read these words on the occasion of her graduation from Judson Sunday school. We read Eccliastes, the kids sang city of immigrants wearing Trump wigs reminding the world this is a city of immigrants. We all sang Turn, Turn, Turn and When I'm 64. And the service reminded us of passing time. Andy sermonized about the god in every story in this Naked City. And greeted our friends at Judson. And number two said goodbye to eighth grade. As i write she's finishing her last day of school, after a decade.

Caroline and I first started talking about writing a book about Brooklyn when we returned from California a decade ago, finding the borough in the process of a new set of transformations. Its been a wild decade. We'll miss Brooklyn while we are gone. But are excited to share her wonderful pictures and the stories we've traced about the borough with Mark Noonan and so many other friends as the waterfront has changed and shifted through time. Now our book Brooklyn Tides is scheduled for an October release.

Finishing the service we played in the grass in the park, went skateboarding and reveled in the passing of time. We've been here longer than anywhere else i've lived in my life, more than the South, more than Texas, more than anywhere. With all its problems, its home.

We'll be away much of the summer. But so far the summer has been grand, with dinner parties and lots of lots of glorious days out in the streets, the parks, and public spaces of NYC.

We're truly lucky to be here.

Postscript

After I finished the blog, Andy sent me a copy of his Kids Day sermon. Here it is in its entirety.

Andy, of Judson Sunday School, wanted her to read these words on the occasion of her graduation from Judson Sunday school. We read Eccliastes, the kids sang city of immigrants wearing Trump wigs reminding the world this is a city of immigrants. We all sang Turn, Turn, Turn and When I'm 64. And the service reminded us of passing time. Andy sermonized about the god in every story in this Naked City. And greeted our friends at Judson. And number two said goodbye to eighth grade. As i write she's finishing her last day of school, after a decade.

Caroline and I first started talking about writing a book about Brooklyn when we returned from California a decade ago, finding the borough in the process of a new set of transformations. Its been a wild decade. We'll miss Brooklyn while we are gone. But are excited to share her wonderful pictures and the stories we've traced about the borough with Mark Noonan and so many other friends as the waterfront has changed and shifted through time. Now our book Brooklyn Tides is scheduled for an October release.

Finishing the service we played in the grass in the park, went skateboarding and reveled in the passing of time. We've been here longer than anywhere else i've lived in my life, more than the South, more than Texas, more than anywhere. With all its problems, its home.

We'll be away much of the summer. But so far the summer has been grand, with dinner parties and lots of lots of glorious days out in the streets, the parks, and public spaces of NYC.

We're truly lucky to be here.

|

| The night before leaving. |

After I finished the blog, Andy sent me a copy of his Kids Day sermon. Here it is in its entirety.

From 0 to 60: A Reflection on the Measure of Time

by

Andrew Frantz

For Judson Memorial Church

June 11, 2017

In this short Life

That only lasts an hour

How much – how little – is

Within our power

Emily Dickinson

Last year I received an email

from an old college buddy of mine, Mark Biddle, proposing a reunion take place

in the summer of 2017. The email was

also addressed to four friends of ours – Jim Nogalski, Rich Lloyd, Ben Leslie

and Douglas Sullivan-Gonzalez. Other

than Doug, I haven’t seen these guys since we were all students together at

Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama, way back in 1979. However, more shocking than hearing from Mark

after all these years is the reason for our reunion: we’re all turning 60 this year.

That’s right, in my case, on

July 19th, a mere 38 days from today, I will say goodbye to the last of my

F-word birthdays. Now I know I don’t

look 60. I don’t mean to brag, but it’s

a medical fact. Recently, I had a doctor

assure me that I looked “nowhere near 60.”

Okay, so he wasn’t exactly a doctor; he was my acupuncturist’s college

intern, who, while filling out the required paperwork for my session asked for

my age, and when I said, “I’ll be 60 this summer,” he went off on me like

someone trying to talk a jumper down from the Brooklyn Bridge: “No way!

You don’t look 60! I swear you

don’t look anything like 60! Honestly,

I’m not just trying to be polite. You

look nowhere near 60!” Alright, alright,

I won’t jump.

But to paraphrase Gloria

Steinem, this is what 60 looks like.

It’s probably a lot hairier than any of us imagined it could be.

As for that reunion I

mentioned, it’s going to take place one month from today, July 11th. Mark and his wife have graciously invited us

to spend a few days at their place outside of Richmond, Virginia. The six of us are positively giddy at the

prospect of seeing one another again. Over

the past few months, the emails have been flying back and forth as we plan all the

necessary details: Who needs

transportation? Who has become a

vegetarian? Who drinks what? We’ve never sounded more like the geezers we’ve

apparently become – “Have you got a Keurig machine?”

When I reflect back on my college

days with those guys, I can’t help but think of a particular poem by Emily Dickinson,

and here is where I do mean to brag. This

past winter, I set a goal for myself to read all of the almost 1,800 poems of

Emily Dickinson. It took me into the

spring, but I did it. Miss Dickinson’s

poems are, of course, wonderful and I highly recommend you read them all, with

the caveat that you not wait until you are about to turn 60 to do so. There is an awful lot of death in those

poems. Some hope, too, here and there –

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers”; “Hope is a strange invention”; “Hope is a

subtle Glutton” – Emily’s idea of hope might have changed through the years.

The poem that comes to mind is

this:

We met as Sparks – Diverging

Flints

Sent various – scattered ways

–

We parted as the Central

Flint

Were cloven with an Adze –

Subsisting on the Light We

bore

Before We felt the Dark –

A Flint unto this Day –

perhaps –

But for that single Spark.[1]

We met as sparks. Actually, we met as ministerial students, the

six of us, preacher boys, if you will, each of us believing we had been called

by God for some purpose. We’d come to

Samford University, of all places, this little Southern Baptist school, to try

and better understand both our calling and the caller.

Sometimes when I picture

myself going off to college, a young ministerial student, I’m reminded of the

movie A Christmas Story, the 1983

holiday classic about nine-year-old Ralphie Parker who desperately wants a Red

Ryder 200-shot Range Model air rifle for Christmas, only to be told by his

mother, his teacher and a department store Santa, “You’ll shoot your eye

out.” Do you remember the scene in which

Ralphie’s little brother Randy is getting ready for school, his mother stuffing

him inside a gigantic snowsuit, complete with clip-on mittens, boots, a woolen

hat underneath his hood, and on top of everything, she wraps his entire head

inside a scarf that must be 20 feet long?

Randy cries, “I can’t put my arms down!” before waddling off to school.

That was me – Randy Parker –

wrapped up tight from head to toe in the faith instilled in me by my family and

my hometown church. A faith which,

however sincere, never asked me to think so much as it preferred I

believe. A faith in which I was never

challenged to question so much as I was persuaded to regurgitate, with the

implied penalty of hellfire and damnation for all those souls who strayed from

the path.

Enter the five reprobates

with whom I’ll be reuniting next month – Mark, Jim, Rich, Ben and Doug – and

there were others, of course.

We lived in the same dorm, we

took many of the same classes: homiletics

– how to preach; hermeneutics, how to exegete (still one of my favorite words)

or interpret the scriptures – which remains the $64,000 question, doesn’t it?

We learned Biblical

Languages, Hebrew and Greek. There is

nothing like the declension of nouns and adjectives in your “Baby Greek” class,

as we called it, to cause you to wonder if perhaps the concept of biblical

inerrancy would fare better if God had just spoken English.

We studied archaeology together

– what do you mean there is no historical evidence of Moses or the Exodus?

We read Bonhoeffer and

Niebuhr, we talked Kierkegaard and argued Tillich over midnight pancakes at

IHOP. We questioned and challenged one

another.

One day, one of the guys

handed me a book by the then-considered renegade, Episcopalian Bishop John

Shelby Spong, entitled This Hebrew Lord,

with its opening poem, “Christpower”:

Look at him!

Look not at his divinity,

but look, rather, at his freedom.

Look not at the exaggerated tales of his power,

but look, rather, at his infinite

capacity

to give himself away.[2]

You read a book like Spong’s

and you can feel the floor beneath your feet begin to shift as, for the first

time, there is the hint of a God who might be outside all of the entrance exams

and rules and regulations with which you’ve grown up. And one day, you happen to catch sight of

yourself in the mirror looking a lot like Randy Parker from A Christmas Story; you realize you can’t

move your arms, and you find yourself asking, “Why am I wearing this damn

scarf?”

If all of this sounds a tad earnest,

then I suppose I could tell you about the time Jim Nogalski decided to

celebrate his own birthday by making a chocolate cake filled with Ex-lax

laxative, and serving slices to everyone who would take one. Have you ever known a college student to refuse

a free slice of cake? My friend Rich

Lloyd had two pieces. It just wiped him

out.

Or I could tell you about a

day during our senior year when the guys were teasing me about something, and

much like the recent episode featuring the Mets mascot, Mr. Met, I responded by

giving them the finger. One of them took

a picture but I paid it no mind. Later

that semester, I was invited to preach before the university in convocation, a

nice honor. Come the day, I’m sitting up

on the podium, nervously waiting to speak, when I happened to notice the guys sitting

on the front pew of the chapel, all of them grinning like a bunch of fools. Slowly, they began to unbutton their shirts,

revealing t-shirts emblazoned with that picture of me giving them the finger.

There were road trips and

dormitory hall wars and . . . well, “time it was and what a time it was.”[3] Never in our wildest dreams could we have

imagined a day when we would all be turning 60 together, and yet, here we are

in the future, wondering where all the years have gone.

Today, I find myself asking,

how do we measure time? By the circled

date on a calendar, the concentric rings within our tree of life? Do we measure time by the accumulation of

aches and pains and scars or the wrinkles not visible in our photographs and memories? Do we measure time by the growth of our

children, by our changing landscape, or by society’s progress or lack thereof?

Alan Lightman’s 1993 novel, Einstein’s Dreams, from which this

morning’s New Testimony was taken, is set in Bern, Switzerland, in the spring

of 1905, as the then 26-year-old patent clerk, Albert Einstein, was preparing

to publish his theory of relativity. The

novel is a series of dreams in which Einstein measures time in various

ways. In one dream, time flows

backwards. In another, time is visible –

one can actually step into the future. In

yet another dream, time is more quality than quantity, measured not by clock or

calendar, but by the color of the sky or the feeling of happiness when a person

enters a room. It’s a rather strange

novel, but I liked it.

If there is one dream we all

may have in common it would be the dream, read earlier this morning, in which

time stands still.

Parents, let me ask you, what

would you give to be able to stop time at the moment of your child’s first step

or their first word or a time when your children were small enough to be able

to crawl up onto your lap and, that most magical of words, cuddle?

Or since we’re fantasizing,

let’s leave the kids at home!

Who among us hasn’t dreamed

of returning to that place where you were young and – how did Hoagy Carmichael

put it?

When our love was new

And each kiss an inspiration

But that was long ago

Now my consolation is in the

stardust of a song[4]

Maybe we can stop time.

In an essay entitled “The

Temporary Universe,” Alan Lightman wonders

why we long so for permanence, why the fleeting nature

of things so disturbs. . . . We visit and revisit the old neighborhood where we

grew up[.] We clutch our old photographs. In our churches and synagogues and mosques,

we pray to the everlasting and eternal.

Yet, in every nook and cranny, nature screams at the top of her lungs

that nothing lasts, that it is all passing away.[5]

Lightman says,

Suppose I ask a different kind of question: If against our wishes and hopes, we are stuck

with mortality, does mortality grant a beauty and grandeur all its own? Even though we struggle and howl against the

brief flash of our lives, might we find something majestic in that brevity?[6]

For the writer of the Book of

Ecclesiastes, time is measured in seasons and the responsibilities which make

up our days: “To every thing there is a

season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven.”[7]

All my life, whenever I’ve

read this passage of scripture, or listened to someone expound upon it, the

emphasis has always been on the word “time.”

And as beautiful as the passage may be, it has always struck me as having

something of a “Duh, thank you Captain Obvious” quality about it. Of course, there is a time in your life when

you are born or a time when you laugh or cry; how exactly does that qualify as

“Wisdom literature”?

But recently, I came across something

that just rocked my world, theologically speaking. In his book The Great Poems of the Bible, James Kugel, who for 21 years, was

the Starr Professor of Hebrew Literature at Harvard, informs us that “[t]he

word for ‘every’ or ‘all’ in Hebrew can, as a noun, mean either ‘everything’ or

‘everyone.’ Elsewhere in the Bible, the noun

usually means ‘everything,’ but in the Hebrew of Ecclesiastes, ‘everyone’ is

often what he means[.]”[8] Thus, the more accurate reading would be,

“For everyone, a season, and a time

of [doing] each thing under the

heavens[.]”[9]

Brothers and sisters, if you

will permit an old preacher boy a moment of exegesis, to my mind, Kugel’s

translation changes everything, no pun intended, broadening the meaning of the

passage, adding a touch of empathy.

For however different our

lives might appear to be, and I mean to take nothing away from anyone’s

individuality, what the writer of Ecclesiastes is telling me when he says, “For

everyone there is a season,” is that

our lives are a series of shared experiences:

birth and death, love and loss, laughter and tears. We are not alone. I may understand you and you may understand

me because each of us has stood where the other is standing. Given our present political climate, it would

seem to me a touch of empathy is needed now more than ever.

Perhaps time is measured by

the seasons of our lives, and perhaps those seasons are measured by how we

measure one another.

This July 19th, my mother, who turned 83 in March,

will call to wish me a happy birthday, God willing, as she does every year. Her phone calls always go something like

this. First, she’ll wish me a “Happy

Birthday!” and say, “I remember the day you were born, it seems like it was

just yesterday.” Next, she’ll compliment

me on what an easy birth I was. I’ve

never known how to respond to that: You’re

welcome? I try not to be a burden on

anyone? Then we’ll chit chat about how

old we’ve both become, before my mother will inevitably ask, “Well, do you have

any words of wisdom to offer now that you are” however many years old I am?

For most of my life these birthday phone calls

have come so early in the morning, I can’t even recall my name, let alone offer

any Ecclesiastes-like words of wisdom.

But this year I’ll be turning 60, so I should be wide awake because

that’s what we old people do – we wake up early. So what words of wisdom shall I offer her, or

my fellow reprobates when we gather together next month, or what shall I leave

you with this morning?

To be honest, I thought that Ecclesiastes-thing

was pretty good, it would be kind of hard to top that. How about this: Everything I have come to believe about God I

have learned from living in New York City.

The idea which first took root in me some forty years ago while hunched

over a dorm room desk in Birmingham, Alabama, that God could be greater than

all our limitations, has never been more real than it is right here and right

now.

And while there might be eight million stories

in the naked city –

City of black, city of white, city of every

shade in between.

City of gay and straight.

City of Hindu and Muslim, Christian and Jew.

And, yes, city of immigrants, the documented

and the undocumented –

I believe God is in every last one of our

stories. For in our great city’s

diversity lies the breadth and depth and mind and even pleasure of God.

These are difficult times in

which we find ourselves, of that there is no doubt, and yet, in the words of a

very hopeful Emily Dickinson, “In this short life that only lasts an hour, how much is within our power.”[10]

Amen?

Amen.

*****

Ancient Testimony: Ecclesiastes 3:1-8

New Testimony: from

Einstein’s Dreams by Alan Lightman

There is a place where time

stands still. Raindrops hang motionless

in air. Pendulums of clocks float

mid-swing. The aromas of dates, mangoes,

coriander are suspended in space.

Who would make pilgrimage to

the center of time? Parents with

children, and lovers.

And so, at the place where

time stands still, one sees parents clutching their children, in a frozen

embrace that will never let go. The

beautiful young daughter will never stop smiling the smile she smiles now, will

never lose this soft glow on her cheeks, will never grow wrinkled or tired,

will never get injured, will never unlearn what her parents have taught her,

will never know evil, will never tell her parents that she does not love them.

And at the place where time

stands still, one sees lovers kissing in the shadows of buildings, in a frozen

embrace that will never let go. The

loved one will never take his arms from where they are now, will never give

back the bracelet of memories, will never journey far from his lover, will

never fail to show his love, will never become jealous, will never fall in love

with someone else, will never lose the passion of this instant in time.

Some say it is best not to

go near the center of time. Life is a

vessel of sadness, but it is noble to live life, and without time there is no

life. Others disagree. They would rather have an eternity of

contentment, even if that eternity were fixed and frozen, like a butterfly mounted

in a case.

[1] Emily Dickinson, Edited by Thomas H. Johnson, The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson

(Boston: Little, Brown & Company,

1976), 448.

[2]

John Shelby Spong, This Hebrew Lord

(New York: The Seabury Press, 1974).

[3]

Paul Simon. “Bookends.” Bookends. Columbia Records, 1968.

[4]

Music by Hoagy Carmichael, lyrics by Mitchell Parish. “Stardust.”

Mills Music (Publisher), 1929.

[5] Alan Lightman, The

Accidental Universe: The World You

Thought You Knew (New York: Vintage

Books, 2013), 24.

[6]

Ibid., 35-36.

[7]

Ecclesiastes 3:1 (KJV).

[9]

Ibid.

[10] Emily Dickinson, The Complete

Poems of Emily Dickinson, 448.

No comments:

Post a Comment