On the Road with Dad, on a hero’s journey, infinite, still moving between books and poems, letters and memories meandering the cul de sacs of my mind, Eight Years Later #RIP POP

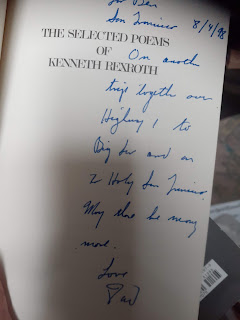

Looking through my books the other day, I found a dedication inside a volume of Kennth Rexroth poems from Dad:

“To Ben, on another road trip together over highway 1, to Big Sur and Holy San Francisco… May there be many more. Love Dad.”

That was from an August 1998 trip from Long Beach to San Francisco together.

Dad carried Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch by Henry Miller, reading me quotes:

“If we are always arriving and departing, it is also

true that we are eternally anchored. One's destination

is never a place but rather a new way of looking at things.”

Dad was always Pervical, the wanderer, always striving, always looking, reveling in the mystery of it all, looking like few else I’ve known, finally to retreat back to the South, back inside himself, seeing the universe with his eyes closed, returning to the the domain he’d looking for inside himself.

Still looking, Miller reminded:

“Surely every one realizes, at some point along the way, that he is capable of living a far better life than the one he has chosen.”

Now, I look at that beaten up old volume in my pile of books on the floor in my office.

These days, the road trips are memories, taking us down into oblivion, smoking a cigar on the road, listening to Tom Waits, with Jack and Dean, Carlo and Sal, heroes appearing and disappearing, making cameos, “roll[ing] through San Francisco…” again and again and again.

Dad and I were always on the road.

Driving across Texas, up and down the California Coast, to Mexico, or East to the farm in Bridgeborough Georgia; it was our happiest place together, a journey, not a destination.

We’d mark up volumes of poems, or gossip about mom, divorce, his parents, Kirk, his brother, my brothers Will and John, on and on, chatting about the beats, mind breaths, whose prose we liked, Jack K or Allen G’s, on and on.

We both liked Allen more.

But understood the myth of the road that Jack traced for all of us; it involved all of us.

Dad always reminded me he was in attendance at the Six Gallery reading of Howl, October 7, 1955, in San Francisco in attendance with Jack K and Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Or was this another embellished myth?

I wouldn’t put it past Dad.

Although he always loved TS Elliot and Robert Frost and Rumi, Papa Hemingway, the collective mythology of the Beats inspired more than any of the rest. Book after book of it, he read, jotting down notes, and drafted his own travel logs.

28 July 1968, he wrote his parents from the Raffles Hotel Singapore, after leaving Afghanistan:

“Dear Parents,

The Afghanistan leg of the trip is over. We toured the entire country, including the extraordinary rough Northern road up to the Soviet frontier. The country was extremely beautiful. Sort of like midway through Yellowstone Park day after day.. We came across a canyon to rival Grand Canyon, ie five miles across and two thousand feet from top to bottom…”

Stories of meeting refugees, a mother in need of help, with an injury they wrapped, a starving child, a cup of tea with a man selling a rug, an afternoon meeting a few friends, repairing the land rover, that was always breaking down.

He was on the road, creating his own mythology, with Mom and his college and army buddies, Fred and Tad and Richard, just as the beats had done, sucking the marrow out of life, learning from it, growing, moving, exploring a great unknown, a mysterious life worth living, worth experiencing, worth learning about each other, in a collective daydream.

When we drove, we talked about those adventures, drinking beers in parking lots, pulling daisies as Jack and Neil and Allen wrote:

“Pull my daisy

tip my cup

all my doors are open

Cut my thoughts

for coconuts

all my eggs are broken

Jack my Arden

gate my shades

woe my road is spoken

Silk my garden

rose my days

now my prayers awaken…”

Our prayers awoken, we talked about his family farm where he retreated, leaving it behind, the illusions of land ownership, the fallacies, poems and stories, the space between god and the sublime, that was the journey for him.

His 1961 journal, from his army days at Ft Benning, is full of musings about travel and books and feelings:

“Reading coming along well completed Notes from the Underground…” He seems to have regarded the underground man as a “fool” (although i can’t make out the handwriting for sure). Still, “the book put me in something of a tailspin for a few days,” says Dad, in his familiar lament. The tailspins were many for him. “Placed my thoughts back on the forbidden topic of

Life

Where

How

Why…”

More plans and thoughts about what to do before law school, nearly done with Harvard, having been kicked out a couple of times, flunked out, left town, gone west and trying to get back on his feet, sitting in an army barrack, ever searching, drafting lists of more books to be read:

“Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

Thorough, Walden

Emerson, Essays,

Aquinas, Introduction.

Trip

Having been considering travel plans I want to make….

Sentimental journey with Stan through entire US for six weeks

a)by gulf eating seafood

b) New Orleans for a good meal and bar

c) Houston buy a lot

d) Mexico City and whatever ocean.

e)Oklahoma

f) San Francisco by way of Albuquerque

g) Chicago

h)Pennsylvania

The trip with Stan I think would be necessary before I go back to school … camping, little things… thoughts…”

We never heard from Stan again, especially after Dad got back to law school and reconnected with Fred, his best friend from undergrad years there in the mid 1950’s.

And travel they did. Five years later, notes from an old law journal dated June 6th, without a date, “50 miles out of Zagreb.

When I was fifteen years old I announced that I would travel around the world twice; once east to west and once north to south, one day out of Vienna, the shoddy gateway to the east and once glorious window of Christendom. Dorothy came over two weeks early for the trip and I spent 9.5 days of that time preparing the land rover in Vienna complete with paper, spare parts, and trip equipment… weeks blurred the focus of the trip, but last night we sat late and discussed the trip. We have broken loose of Georgia, Cambridge, and recent accomplishments in order to enter a world which know nothing of me, to apply tools which are unfamiliar, to leave protected tools and techniques. We leave behind the known and familiar in order to grapple with the challenge of a new expanse… We will return to the challenge of Cambridge at the end of the summer… It would prove to be the best battle we ever fought…. Why did Marco Polo do as he did? Or did Odysseus leave Ithaca, sailing the Mediterranean.. We left Vienna at eight this morning after the usual grapple with Fred and Tad about sleeping late. Traveled to the Yugoslav border. The countryside was picturesque, mountains and power which never fail to delight…”

Trip after trip, two to the Middle East in the 1960’s, before and after law school, Dad corresponded with his parents the entire time, trying to find something and make sense of who he was. You always take yourself, as they say. Fred, Dad’s roommates and one of the traveling companions who slept late, finally gave up on trying to impress his parents. A quarter century later in Dallas, Dad was still reconciling his life and travels, the practice of law, his professional ups and downs as a college professor and corporate lawyer, a stroke which nearly killed him, with memories of his father’s screams and demands that he could never quite shake. A poem in his collection speaks to that sentiment:

“He picked me up from the crib.

And his smile was all the joy I ever sought to know.

Always

Eternal

Potent

Forever

Then it broke with the bomb of Pearl Harbor.

Death broke open me

With the death moral

And a father who grew up in Georgia.

And then went away to the deprivation of a triage

In a lone hospital

When he returned

he brought with him the horror

Of his

And all our parts

And very soon

He reached out at me with madness in his eyes.

Eden was gone

Dad was

And I was left

And finally alone to live in the world of men.”

The road had not always been kind to grandpa, although he loved driving from Thomasville to Louisiana, and staying in Florence, Italy, where he spent years with Grandma after he retired in the 1960’s. It was his years in that old triage hospital that left him lost and violent, beating Dad’s love of him when he returned from the war.

Grandad finally shuffled off in 1985.

Fred drove us from Dallas through Louisiana back to Georgia, through the woods my grandparents in Moultrie, Georgia.

Six years later, Fred shuffled off, from complications of HIV/AIDS, losing his mind.

Dad would spend the rest of his days reeling from the experience of knowing these two men, scared by his father, and charmed by his experience with his thirty five years of friendship with Fred.

Shortly after Fred’s death, his one brother died prematurely, after quitting drinking.

Dad’s tailspin left him reeling.

He retreated back to the family farm he inherited from his father.

And had a breakdown.

When he came out of it, he was committed to taking his life in a new direction, making good on the graveside conversion he’d experienced after nearly dying of a heart aneurysm almost two decades prior, a commitment to give his life to god if survived, signing up to join the seminary in Chicago and becoming an ordained priest.

Doing so, he was forced to reconcile a few of the parts of himself he tended to compartmentalize. There, he hoped to finally come a little closer to answering the question about the relationship between poetry and the sublime, god and the unconscious he’d been asking for the previous five decades. At Chicago Theological Seminary, he looked at the world and wondered where he fit in this place. The road was a central theme of his “Cultural Autobiography” written in the mid-1990’s in Hyde Park, across the street from the University of Chicago. It is perhaps my favorite of Dad’s reflective essays:

Beginning with the familiar Tennyson epitaph, “I am a part of all that I have met,” it reveals something of his thinking about his father, his faith, and the culture of his childhood:

“Much of my cultural formation is a result of the accidents of geography and time,” Dad begins, in perhaps my favorite of his essays and poems. “I am a white male southerner in early old age. I was raised in a Puritan Calvinist tradition which extends back to the Midway Church, a Presbytian congregation that immigrated to Georgia from Massachusetts Bay in 1754. My people have always been primarily agrarian, with a sprinkling of preachers and doctors, who have lived for the last two hundred years in three counties in southwest Georgia. The road which passes in front of the family farm is known locally as High Ridge Road, but finally its name is the Thigpen Trail. It was cut by Col. Thigpen in the early seventeen hundreds as a military road into Spanish Florida. My great grandfather marched off on this road in 1864 at the age of 16 to fight Yankees. His primary memory of the campaign was that of hunger.”

Dad always talked about the Thigpen Trail, a hot road in front of our farm.

Dad loved his heritage; he also hated it. He detested his father, and seemed to appreciate what he brought him. Fifteen years after arriving home from the Great War, Grandad advised his son to complete his military service in a timely fashion and stay as far away from Viet Nam as possible. The US had no business there, he told his son in officer’s candidate school in Ft Benning. His ecumenical sophistication, this pluralism is highlighted in Dad’s Cultural Autobiography:

“This narrow orientation was broadened by life in a free-thinking and broadly cultured family. My father and five uncles, with the exception of two, were educated at Harvard. They were all widely traveled and had a great respect for classical culture. This broadness of viewpoint was carried over into religious training. My father, though a deacon in the Presbyterian Church, and careful of our formal training in that church, refused to allow us to be confirmed until we had demonstrated to his satisfaction a rudimentary grasp of Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism. He was careful to emphasize to us that our Christian faith was only one in a world of legitimate faiths.”

Dad had seem hero with a thousand faces, a buddha in San Francisco, a Mayan ruin Mexico, A Hindu turned Buddhist temple in northern Cambodia, along the road, a meditation on the mystery of them all. “Interest in foreign cultures and study and travel to different regions became a serious avocation,” Dad concludes. “As a wistful agnostic and searcher, this travel took on much of the auro of religious pilgrimages. As I traveled and studied, I came to realize as a firmly grounded personal truth, the precepts my father taught me: we are all finally, though different and glorying in our differences, one species. All communities are at root religious. All religions are worshiping the same God, and religions share the same authenticity. I finally realized that God was not to be found in Luristan or any of other distant place, but within my own and all our hearts.”

That does not sound like a man who resents his father, although he does concede his family experienced as much trauma, division and strife as the next. The wounds were many when the belt found its way onto dad’s backside, the screams, and confused rage, between love and anger, confusion and confoundedness followed.

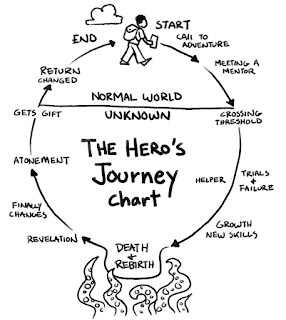

Dad left home only to return like the hero on a journey that Joseph Cambell sketched in Hero of a Thousand Faces: “It would not be too much to say that myth is the secret opening through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into the human cultural manifestation. Religions, philosophies, arts, the social forms of primitive and historic man, prime discoveries in science and technology, the very dreams that blister sleep, boil up from the basic, magic ring of myth.”

Still Dad searched the world over, sharing a kindred spirit with the Beats and their tales of cosmic road trips through Holy America.

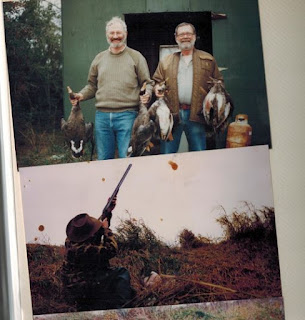

When I was in high school, we went to see a one person play about Jack Kerouac, as he traced his story about his buddies, the buddies we see pictures of, we hear about in the novels, wondering about Dean, running into Carlo, getting in trouble, knowing any trip could be their last. Dad always knew that as we drove through Louisiana or Texas.

It was our version of on the road, where Jack wrote about seeing Denver in the distance:

“Like a promised land, way out there beneath the stars, across the prairie of Iowa and the plans of Nebraska and I could see the greater vision of San Francisco beyond, like jewels in the night…”

The road was a space between this life and that, this world and that, these responsibilities back home the open road ahead. A letter to his parents from Cambridge, Mass, October 1956 spoke to these sentiments:

“The life is so complex and there are so many demands made on a person. People want me to do things…” he says, seemingly thinking out loud on Columbus Day, Columbus Day 1956. “Well, back to the salt mines, I guess. Must read some of the Plato that I read this summer, and oh, quiet a bit more.”

Letter after letter I dig about, correspondence from those old college roommates decades later, old girlfriends, letters from students and friends, countless to and from his parents, trying to find himself as he wrote.

No wonder the obsession of the Beats and Jack’s writing:

“I was just somebody else, some stranger, and my whole life was a haunted life, the life of a ghost. I was half way across America….”

I guess we all are; Dad certainly was.

We were on trip after trip, never imagining our last trip to Breaux Bridge, a small city in St. Martin Parish, Louisiana, a dozen years ago would be our last. We talked about life and sweet death, my friend who had just died of an overdose; got lost on the way home, stopped for gumbo at a road house, and listened to Loretta Lynn, chatting away all the way back to Texas. There wouldn’t be any more, although I wish there were. He gradually stopped coming to New York.

Travel was too hard. He stayed at and looked at the light pour in through the window.

And eight years ago, we talked about poems before he went to sleep, never waking. Will and I brought a few of his ashed sprinkling them along the road from the Sam Houston forest to New Orleans, and into the Mississippi river, where he joined Huck and Jim and the other gods and heroes, ashes to ashes.

“‘That's Dean, he’s always around,’” writes Jack toward the end of On the Road.

“‘Someday Deans going to go on one of these trips and never come back….’”

Writing here in Brooklyn, I look down at the pile of letters and journals, stories of a lifetime, correspondence about theology and friendship, poems and plans, trying to make sense of it all, first drafts of my novels and books, he was reading, unending poems on bar napkins.

Now, they are in the stories in my mind, reading about it all, merging his myths with my own, with the gods, still on the road.

March 27th, 2022, the family and I sat the old El Quixote restaurant, next to the Chelsea Hotel where Dad used to stay, a home away from home, where we listened to Bud Powell records and read poems, and talked about that rendezvous between Janis and Leonard. Dad smoked cigars and drank whisky, reading until I got there and we went out for dinner next door or to the Village Vanguard, only to return to the Chelsea Hotel, where we talked even more. RIP Jack Shepard... eight years later... still with us in stories and memories and inscriptions from Kenneth Kexroth poetry volumes and road trips... and nights out at El Quixote on 23rd street, remembering sitting up all night talking. The conversation continues.

No comments:

Post a Comment