Leaving for Warsaw on October 10th, I have more questions than I have had at any point in this research.

When Poland elected their new Law and Order government in 2015, crowds of thousands and thousands marched on Warsaw in defense of democracy.

Over the next few years, elected leaders stacked the courts, as Poland went on to ignore the rulings of the European Union, that backs it, funding roads and infrastructure. Between Poland and Hungary, people wondered about the “Illiberal” trend in Europe. We’d certainly seen it in the US. Poland followed with a full scale ban on abortions, echoed by the US, sending the policy back to the states.

Why the rightward tilt, I think. What will Warsaw be like? I know it was bombed during the war. What happened to Solidarity? Lech Walesa wondered himself, giving a speech to congress on the 30th anniversary of the Fall of the Wall, as well as an interview with Foreign Policy in 2019. In it he reflected on the shifting legacy of the revolution in which he took part as a union organizer.

“With the support of the United States and many others, we succeeded in eliminating this old division in the world. But then the question arose: What should happen next? How should the world develop? And this is my message today: We have not truly constructed anything new in the world. And there is a loss we have suffered.

FP: What is that loss?

LW: The loss is the leadership position of the United States. Which is a very bad situation for the world. There is no leadership. Previously, when we were involved in our struggle, we used to have the evil empire and the good empire. And the ultimate refuge for the world.

FP: You mean leadership in terms of values—political and human values?

LW: We defeated communism. And the organizations we had in place then somehow proved effective in that part of the world. But have we replaced any of those organizations since then? One era has come to an end, and another one has not fully emerged. And we are in between… The point is, we still don’t trust each other after the old era. And now we need to be constructing something completely different. The question is, what?”

That is the question. The US is not the bastion of freedom supporters might have imagined. And Europe is facing its own myriad of crises. And I’m wondering what the Poles think of this.

One of my interviewees suggested I try to understand a few dynamics, including what happened in Wołyń, the World War II era slaughter of Poles at the hands of Ukranians. Try to understand the Polish Ukrainian conflict from our perspective, he told me. Try to understand what happened in Wollynebeing? Look into Lviv - the Polish army coming to the city in 1920/21, the Lithuania - Wilno - conflict.

Today, Poland is also on the front lines of the Ukrainian Refugee Crisis. “If you look at a Ukrainian and a Pole, you won’t be able to tell who is who, and this undeniably contributes to the willingness of Poles to help,” said Professor Brian Porter-Szucs after the war broke out. “Sadly, racial categories have played an unconscious but very real role in facilitating assistance for Ukrainians, even as it has been denied to those coming from outside Europe. Moreover, much of Ukraine was once part of the Polish-Lithuanian Republic, so the regions have a very long and intertwined history.” And certainly this dynamic shapes the treatment of refugees here.

Refugees, it seems to be so much about refugees.

Five years ago we were in Krakow and Auschwitz. Yet, there was more to see and try to understand, particularly in the capital.

On the train moves from Berlin to Warsaw, woods and small train stations, passing by as the train moves. What's out there in the woods, I see outside my train window? What of the indignities suffered in Kosinski’s Painted Bird, his story of a young boy, Jewish, traveling in Eastern Europe, seeking refuge during World War II or Mr Gustave’s adventures on trains, journeys through the countryside in the Grand Budapest Hotel. “You filthy, godamn, pock-marked, fascist assholes! Take your hands off my lobby boy!” he screamed on a similar train, as the army sought to take away his traveling companion. Gustave was nowhere to be seen on my train. Why so many massacres, slaughters, I think writing in my journal, and the door to my train car opens. A tall, lanky gentleman walks in and greets me. He’s wearing a red and white sweatsuit with the word Poland on it. He invests in cryptocurrency.

“Where are you from?” he asks, amicably. We start chatting, as he flips through the papers.

“World War coming in Europe,” he says. He’s from Germany, although he lives in Poland. And worries about the Green Party in Germany, that pushed Germany off nukes, without investing in enough renewables, leaving Germany vulnerable and dependent on Russia.

“There are going to be blackouts in Berlin. No one can handle what's coming. There are a lot of immigrants there. You need a gun. And supplies for two weeks.”

“Does Poland like Germany?” I ask.

“Yes, but now they want reparations for the war.”

“First , the Germans. Then the Russians. That was a rough time,” I reply.

“Yea.”

“It took Germany like a week to take over.” We talk about wars and civil wars and conflicts. “Wealth taxes coming. War coming. Blackouts are coming,” he says. “Poles hate Zalenski. Two million Ukranians are in Poland now. Parts of Ukraine used to be Poland. We want to get parts of the Ukraine back.” He pauses. We take calls or doom scroll. “End days coming,” he follows. “The war is the US fault.”

“Why,” I ask.

“For aiding Maiden Revolution, of February 2014, and NATO. Ukraine is armed to the teeth. The US pushed NATO to the border with Moscow, Poland, Ukraine. Russia pushes back. NATO pushing too far, creating conflict. Still, Poland’s friend is US. Poland likes the US. It likes Europe.” Chatting away, a conductor walks in and asks for the man for his ticket. This isn’t your seat he says. He has to leave. We are an hour of Warsaw.

My train pulls into Warsaw at 740 PM. Same time Will was arriving from Sweden for our meeting. Our last trip included jaunts to Czech Republic, Praha, Pilsen, Regensberg, and Munich. We’d stay in Warsaw for a day and then travel out to Sulwaki. I find my way out of the train station, looking for signs for cars, in between the people, waiting, catching a ride to the Jabeerwocky Craft Beer Pub, on Nowogrodzka 12, walking past graffiti and porn shops along the way. First night is quiet, Polish food and catch up before a big day Tuesday.

We wake early on Tuesday and make our way to meet Gawel, our guide at Sigismund’s Column in Castle Square in the Old Town. Rebuilt in the 1950’s, there is a strange quality to being here to start our tour of WW2 in WARSAW + WARSAW GHETTO on Tuesday, October 11th at 11 AM. Buildings are looking a little dirty. Gawel, our guide, greets us, reveling in the warm weather.

“It's nice you got here now. It's going to be cold soon and the people here are going to burn their trash again this winter. We trade for coal with Russia, or we used to. But now everyone is afraid of Nukes. What do you think of it?” he asks rhetorically. “Chernobyl. We all do. But now it can be a clean, green source of energy. Now the price of coal went up because of Putin. How far are we from Russia?” he asks. “150 K to the Russian Belarussian border.”

“After 1945, Warsaw was reshaped. It had many wars in its 700 years. But with WWII, it lost 50% of its population, 85% of its buildings, bombed,” Gawel begins.

“September 1, 1939, at 4 AM, the Germans opened fire on the Polish fort at Westerplatte guarding Gdańsk, a port city on the Baltic. A tsunami of bullets flew through the sky. The Nazi’s marched in from the North and South, via the Czech Sudetenland. Those in Warsaw from the radio. Few were surprised. Some were pleased, assuming this would be the end of Hitler. School kids relished missing the first days of school. People rushed to the cafes to share a cup of coffee. Poland had signed a pact with France and England, that they would defend one another if any was attacked. All Poland had to do was hold the line for two weeks. Poland held for a month. Yet, few came to their defense. Everyone was wrong. The attage is generals always prepare for the last war. German tanks entered Warsaw on the 8th of September, 1939.

“Hitler was furious Poland fought back. Overseeing the operation, he called for Germans to bomb the castle. 17 September, at 11:15, bombs hit; the clock stopped in the castle. A symbol for Warsaw, it burned to the ground. Today, trumpets play every day at 11:15 recalling the invasion, from the Germans and then the Soviets, east and west. The commander of the Polish Army abandoned the country. Carpet bombing began September 25th, 600 tons on the city. Waterworks were destroyed, so people could not stop the fires. 27 September, Poland surrendered. Starving, people were eating dead horses.

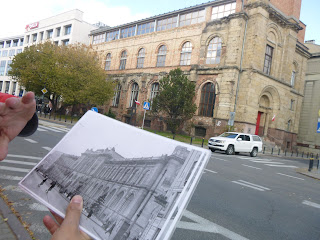

“Poland resisted one month. And then the occupation began. German soldiers entered October 1.” Gawel pulls out a black and white photo of German troops marching where we are standing. Poles were starving and freezing. Three million Jews lived in Poland at the time. Only 10% would survive. Among other things, the Germans suggested the Jews spread disease, harborred communism, supported capitalist exploitation, spread typhus and plague, mixing anti semitism, within an anti communist toxic stew..

The trumpet is playing in the castle. “It's 11:15 AM, 83 years since the castle was blown apart,” says Gawel Poland was invaded three times in the 20th century, he continues with dramatic flair. “Once by Germany, another two times by the Soviets. Hopefully Russia dissolves and the threat ends,” Gawel editorializes. “Today, refugees are going back to Ukraine from Poland. The end of Russia is near. Putin is weaker than he’s ever been. We support Ukraine if anything for our national interest, even if we have not always gotten along.

We walk to the President’s palace, looking at the statue of a poet, Adam Mickiewicz, national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. His poem the Tempest feels apt for the storm Poland endures:

“The sails in shreds, the helm all smashed, the roar

Of waves through blasting storm, and fearful cries

As pumps are manned. From sailors' hands last ropes

Have slipped. The sun in blood sinks down: hope's gone.

Triumphantly the tempest howls; from sea's

Abyss, on watery mountains, death's own genius

Hell bent on transforming Warsaw into a German city, the Nazis destroyed the statue of him. The head of the statue was later found in a trash heap in Hamburg. They demolished monuments to Polish cultural heros, such as Chopin, erasing as much history as they could. Intellectuals and artists, professors and writers were rounded up, taken to the forest and killed shortly after the Occupation began. “Each year, we go to the cemetery, outside town, with lit candles to remember them,” says Gawel.

“If you were a worker, you had to follow Nazi orders, that became almost impossible,” Gawel follows. “No poles could go to parks, or restaurants, or eat meat. That was for the Germans. People ignored the rules. You couldn’t avoid the roundups. Young people loaded into trains, sent to factories. Jews were forced to clean up the rubble from the bombings.

Germany paid compensation to Poland until 15 years ago.

Police are walking to and from as we stand in front of the President’s palace. He’s not too popular right now, says our guide. But if we unfold a banner saying he stinks they will take us in for questioning. Sure we have a constitution. But it doesn’t stop them from asking for identification for safety purposes and bringing opponents in for a day or two. Identification confiscated. Two police walk up and he continues his official tour. Let's not talk about that now, he says. There’s not much of a right to free speech now. The palace became Nazi offices, he follows, as if to throw them off. I’m wondering if Poland is still a democracy. Many are.

A few months before the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944, the Butcher of Warsaw, Franz Kutschera was killed in the streets, just outside where we are standing. Four days later, his fiance was married to his corpse in the same palace. He’d spent years executing Poles in the streets, hanging signs listing the deaths. When he stopped listing them, people worried what had become of their loved ones who’s disappeared. Some even asked for the lists back just so they’d know what happened. “If I had to put up a poster for all the Poles killed here, there wouldn’t be enough trees in the forest for all the names,” he replied, shortly before he was killed.

Poland has been invaded by all of its neighbors, except the Czechs. Even the Swedes invaded here at one point. Four hundred years ago, we invaded the Kremlin, Gawel chuckles. Too bad that didn’t last.

We stroll to Piłsudski Square, an empty park, with no benches, little else. Why do you think this is so empty? We don’t know the answer. A palace used to be here. See those two arches down there. That's all that's left of the Saxon Palace that is being rebuilt now. In 1933, scientists helped crack the Enigma code here, before it was bombed during the war. Today, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is here. The government is trying to rebuild the palace, to distract the world from their incompetence. But the old basements are still here, full of relics. “There is a whole city under the ground here,” says Gawel.

I think the president wants to take our minds off of 20% inflation, says Gawel. The Law & Justice Party came into power in 2015. A right wing party, favoring both nationalism, as well as socialism, if that isn’t scary enough. They rode to power on helicopter money, checks for everyone, essentially buying the election.

Walking to the old Jewish Quarter, we see plaque after plaque for the people killed here. One at the opera, 500 were killed, another at Wola, where some 50,000 were killed in three days in August 1944 as retaliation for the Warsaw uprising, the second largest uprising against the Nazis. THe first was the Jugoslav Uprising, with nearly a half million people. The Warsaw Uprising lasted some 63 days, 150,000 were killed, 90% civilians.

Walking we pass the Bank Polski, still littered in bullet holes from the war, its facade left damaged as a reminder; a monument to Polish Fighters out front.

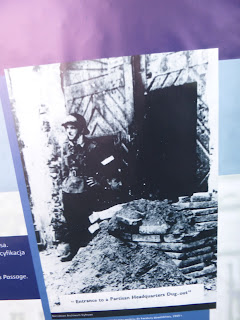

We enter the Muranow, the Jewish district. The Synagogue here was destroyed as a symbolic end to the Ghetto Uprising here of April and May 1943. Standing on the cobble stone street of Nalewki, Gawel tells us stories of the Battle of Muranow Square here, of April. Once this was the center of Jewish life in Warsaw, leading to the Ghetto, where people lived and built a culture. Today, it's the site of a relatively empty park, empty, nothing but trees. The enture district was razed, burned, and bombed, until there was nothing left, not even basements. It was a commercial street, where people sold ties, buttons, and suitcases. Gradually, the Germans discouraged other Poles from entering the district, putting up signs that the area was an infectious zone, setting up lines and checkpoints between Arian Warsaw and the epidemic area, the Jewish area. During the war, the Germans deported other Jews here. They lived in dense spaces, some 40 to an apartment. The plan was to isolate and starve them to death. 150,000 starved. At the Wannsee Conference of January 1942, the Nazis devised the Final Solution for the Jews and others. By July, they started departing them on trains to Triblinka, back and forth for two months, killing 300,000 in two months, 5,000 per day from Warsaw. 50,000 remained in the Ghetto. The Germans wanted to use them as slaves, stiching uniforms in the war effort. Those who remained had nothing to lose. They’d lost everyone. No more following orders, they they decided to fight. Smuggled in weapons through tunnels. Nazis enterring the the quarter to deport them were received with bullets and gun shots. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was perhaps the first large act of resistance in Europe. The goal was to die in the fight. They only had weapons for a thousand. It took Germany a month to crush the uprising. It had taken the some length of time to to take control of France. There were six hidden paths throughout the Ghetto, each laid with traps for the Germans. The basement at 18 Miwa street was thought to be the center of the resistance. The Ghetto was a maze, that the Jews knew. Trapped between burning vehicles, Germans who entered were left to search for one of the six exits, full of gates to other traps. SS soldiers withdrew. They they started burning the buildings, building by building. Those in 18 Miwa were thought to have committed mass suicide, to die on their own terms instead of at the hands of the Nazis. The building eventually collapsed on those inside. Today, the memorial there is also a tomb for the fighters who perished there. The fires ended some 700 years of Jewish life in Warsaw. Some 400,000 Jews lived here, one third of the population of Warsaw. One percent survived. After it was burned, they could not identify anything but the cobblestones. A sign reads: “Graves of the fight of the Warsaw Uprising… Here they rest, buried where they fell, to remind us that the whole earth is their grave.”

Gawel leads us forward to more ruins just discovered. “Ruins are always discovered here. There is another city under our feet,” he says.

We thank Gawel for his tour. He gives us directions to a good lunch spot. And we stop. I have to sit on top of the memorial, meditating on the last hours of those who suffered, who perished below me. It's a lot to take in. Lump on my throat. That was a lot.

We walk, stopping at the memorial for the uprising, the first building built here in 1948, signaling the rebuilding of Warsaw. It would take another quarter century to complete the job. The mental work is still being done. And what of the Ghetto?

We are in a daze. Take a train to lunch, to stroll through the rebuilt old city, struggling to hold on after a deep dive into stories of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and its brutal end, humbled by the horror. We stumbled over a bridge out of the old quarter, into goth night at at Klub Hybrydy, a music venue that reminds us of Berlin, with Avalanch Party, a Bauhaus sound by way of Austin USA. We find ourselves staying up half the night dancing in punk bars, chatting about the uprising, making new friends, learning about Elizabeth Battery, vampires and cannibals and lots and lots of history here, trying to shake it all off, devastated by the history; its hard to shake the horrors.

Next morning, I stroll to the National Museum, taking in centuries of art, images of Dead babies, looking anything but like the Northern Masters I saw in Amsterdam or Brussels, still a majestic collection on this distinct culture. Portraiture, dead babies and pouting buttocks to remind of us life's continuities. And meet Will at the bus stop for a five hour bus ride to Sulwaki, the story of the next blog. We have no idea where the buses leave. But we manage to find it, making our way from Warsaw, to Sulwaki, back to Warsaw, taking in a lot of history along the road. A final night on the road, a final night of music. Each night we were here, we tried to scratch into local music, food, beer, performance art, we found something. What a fascinating, tragic, resilient city....Final night at PERŁA I JEGO STARZY // HMK69 at Klubojadalnia Młodsza Siostra, a quirky music venue they told us about in Suwaki, just down the street from our hotel at Dobra 14/16 00-388 Warsaw, Poland. Lots of college students, great food, and oddball underground spoken word techno, imagining a new reality, rejecting both fascism and communism, looking at something better. Still, it’s hard to shake the scars and move beyond them, the invisible walls, that keep rising.

No comments:

Post a Comment