Arriving and departing is always hard, a bit of chaos here or there, irate border guards, international disputes, tours, interviews, and security guards at old churches, conflicts dating back decades and millenia. I wanted to dig a little closer into the history of conflict, in the area of Southeast Europe often referred to as the Balkans. I’d been to Croatia and Bosnia, the central players in a civil war of the mid 1990s after the fall of the Kingdom of Southern Slaves, known as Yugoslavia. Walking through Sarajevo, two and a half years ago, hearing stories about the conflict, narratives of friends turning on friends, turning on each other, I found myself thinking about the US, the resentments and backlashes over struggles for equality, our Civil War and amnesia. I found myself thinking about Los Angeles and the riots three decades prior, the fear and anger, flames ascending into the sky. “Scream for me Sarajevo,” declared Bruce Dickinson of Iron Maiden, who played there during the siege. Who are your friends? And why do they sometimes turn or harm you, I wondered, an American reflecting on Sarajevo we all have inside of us, hope for connection and anger toward difference, tribal resentments and animosities and a longing to overcome them as people. Wherever we go we bring ourselves, our questions about the world, our external and internal struggles. The Sarajevo project would extend into years of research on what we could learn of the clashes, from Los Angeles to Hong Kong to Sarajevo, Berlin to Belgrade and back. My base would be Berlin, a once divided city, finding its footing, embracing refugees, supporting a thriving club culture.

Will and I started talking about the trip in Prague and Poland, where we traveled on the fall, formalizing our plans over beers at Cafe Kotti in Kreuzberg, on a rainy afternoon in Berlin.

Our first stop would be Bucharest, followed by the capital of Bulgaria on Kosovo and Belgrade.

Should we really try to go to Kosovo?

And if so, how?

What about Belgrade?

It's the Berlin wall of the East, said Manny, when I told him I was going.

Most beautiful city in the Balkans, said a friend at Freie Universitat.

Back and forth we debated, trying to figure our an itinerary, making arrangements for hotels and bus tickets. No trains were available, what days we’d travel and when, until finally we departed.

"The Balkans are the crucible of conflict," says Will, attributing the quote to Winston Churchill. "the Balkans produce more history than they can consume." Apparently, Churchill was speaking of Crete. But the point continues. Its otherring and marginalizing.Still, the history here, between empires and contested histories is ever shifting and dynamic.

Bulgaria is still considered to be a part of the Balkans, although it had nothing to do with the civil war of the 1990’s. It has its own story and conflicts worth learning from.

Feb 25

Will would leave from Stockholm and I’d make my way to the train from Berlin.

Still reeling from a crazy, emotional couple of days. The day before, a peace march for Ukraine ended at Brandenburg Tor, where they shined blue and yellow colors, in solidarity with Ukraine. Very moving gesture of support on a national shrine. Followed by my trip out of wintry beautiful Berlin, by train to the airport to Munich, to catch my flight to Sofia, the first stop of our journey. Snow on the plane, we heard the weather was going to be rough. Terrible winds, flight diverted to Belgrade, and then a jumpy, choppy flight to Sofia, people gasping, crying, praying, up, down, bump, windows shaking, wings jolting. The pilot tried to land, hit a current, swerved out on the way down, too dangerous. I thought of the kids and family I love. Wondered if this might be it. Jolt. Another try or we go back to Belgrade, said the pilot. Slowly we descended, lights of the city in the distance, gradually making our way down to this beautiful, age-old place. Had to walk around, take in the city on arrival,past graffiti, people out, laughing, alive. I'm alive and lucky to be seeing this place with my own two eyes. A week in Sofia, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Belgrade ahead.

Feb 26

Waking up that morning, I looked at my phone, doing a google search about where I found myself, looking at the trees outside my winder, what I was in for, in this capital of Bulgaria. “Balkan nation,” it says. “the second-oldest city in Europe” it goes on, a “confluence of so many cultural and historical influences. Those three elements, history and confluence mixing, thats wat I need to try to understand.

We’ve got a lot to learn.

After breakfast, we stroll to the historic district, taking in the graffiti and trees, the people selling newspapers, and the trams that look as if they’ve been here decades.

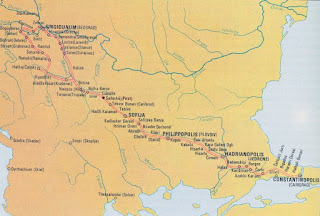

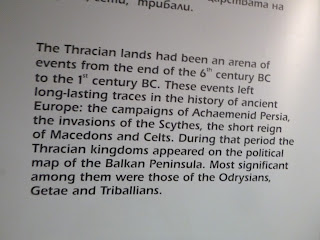

And the tour begins, from the National Gallery to the Archaeology Museum, a former mosque, and history of cultures, Thracian, to Roman, to Khan, Byzantine, Ottoman, into the present. I love this Peacock perched on a fountain, says Will, pointing to an early Christian mosaic, tiles depicting immortal souls, the fountain, life, the tree, rising from it.

“That's it isn’t it,” says Will.

On we read, through the objects, trying to make sense of the history of Serdica, the old name for Sofia, founded by a Thracian Tribe, founded in the 8th Century BC, before the Romans arrived, Marcus Aurelius, followed by Emperor Constantine, and the Edict of Toleration 311, from Roman Emperor Galerius, ending the persecution of Christianity. And the waves of ideas and people continued. 447 the Huns attacked, followed by Kahn in 809.

It's a different storyline, I say to Will, trying to take in the story of this place, becoming Bulgaria, a golden era from 896-927, followed by a dynasty, then taken over during the Byzantine Conquest in 1018, followed by the Ottoman Empire in 1396.

"The whole land has become Slavic and Barbaria," says Constantine the VII in the 10th Century. Waves ebb and flow, no clear line. Today it's a part of the European Community. It's also a part of the East.

“It feels like Europe being imposed on the Steps of Asia,” says Will.

We feel it walking through the Ethnography Museum and into a modern wing, taking in the surrealist paintings of George Papazoff, the Illuminator, movements moving from Paris to Prague to Sofia, ever finding their way. Onward, we walk to the National Archaeological Museum, full of Roman and Ottoman relics, in a former Ottoman mosque, once the Koca Mahmut Paşa Camii. Outside the old mosque, we stop for a coffee before our afternoon tour.

We meet at the Palace of Justice at 4 PM, where Stefan is greeting a group of us from Greece and Italy, for the history of Sofia’s pre communist, post communist days.

He asks everyone where they are from, eventually getting to Will and I.

“Stockholm and Berlin, Americans in socialist countries,” he says to Will and I, laughing.

An amicable fellow, he leads us through the afternoon.

“I love history, talking about history,” he says. Thank you for coming, for giving me a chance to talk about and do what I love. In Sofia, communism is still a controversial topic. Everyone had a job, but no one had freedom to choose. My grandad said it was an egalitarian system. He had a picture of Stalin on the wall. My old grandfather said they were thieves and they built their revolution on the backs of bodies. I’m going to build a story with both sides, he declares, with a grin, walking us through a history of Marxism, a critique of capitalism and a strange practice in applying notions of how to deliver for each according to ability, and need. As Marx put it, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs" Yet, the distribution of goods and services is never quite that sample, free or egalitarian. The system paying you what you need according to your efforts, that can a tricky equation. It certainly was for Bulgaria.

In Lenin / Stalin ideology, each communist country was to go through three stages:

Revolution, rising up, taking power from the capitalists.

Transition - socialism, laying the groundwork for the final step.

Communism.

No one got there, says Steffano. We never achieved it. Never had it. We had Socialism in 1989. We thought we’d achieved it. Some say it's not possible. Stalin ruined it, replaced private capitalism with state capitalism. The Bulgarian journey to Marxism and Soviet Style communism was certainly not a linear route in this, one of the oldest states in Europe, in between empires, exposed to a cross currents, between competing models of fascism and world war. They started the second world war on Germany’s side, attempting to switch sides, before the Soviets eventually invaded, ushering in decades of command economy and Bolshevism, forced into the Eastern Bloc, as they had been with Byzantine and Ottoman empires before them.

Our first stop is at the Church of St George, a rotunda, made of brick, one of the oldest churches in Sofia, a century around for a millennium, destroyed by the US and the communists, allowed to stand during the Soviet Years. Bombed, rebuilt, hidden, obscured, it feels lost. They tried to replace one belief with another. The only way to make communism work was to believe in it. God vs Communism, the kids were told to believe in Stalin not God. Don’t pray. 10% of the population is Muslim. Jews were not telling their kids they were Jewish. Poland was the only Christian communist country, and they overturned it. The only days you could watch American movies were Easter and Halloween. That was their solution to distracting people from going to church, then essentially prohibited, but not necessarily outright banned. Much of it felt that way, a version of communism that was more clumsy than oppressive.

Throughout the tour, Steffano tells us about different leaders, good and bad, forced to navigate the system. Two who stood out were George Dimitrov, followed by Todor Zhivkov, who was the leader of the communist international here for decades, stepping down voluntarily in 1989, avoiding Nicolae Ceaușescu’s fate in neighboring Romania, executed on Christmas day in 1989.

His fate, just a country away, looms large.

History is messy. I remember that period, the joy I had in the spring of 1989, watching revolutions in the air, before the massacre in Tiananmen Square, the Velvet Revolution to follow in Eastern Europe. All day, we navigate throughout this history.

There was something different in Bulgaria.

Following the Russian lead, the Bulgarian communists started shortly after their revolution.

In 1923, they tried to establish collective farms. The result was a disaster. No farmers wanted that. During Ottoman rule, people had owned their farms. They lost them under communism. People were killed, jailed, hung. The Russians had surfs till the 19th century, with no attachment to the land.

On the party lurched forward, navigating the country’s support for the Nazis in the early years of the second war, joining the Axis powers in 1940. 1941, Hitler goes East. Pushes Bulgaria to fight, declaring war on the US and England. The US bombs Bulgaria. Churchill says he wants to see Bulgaria as a potato farm. By September 1944, Bulgaria was trying to play it both ways, with two much much larger foes. With Soviet troops encroaching, it switches sides, before invasion, allowing the Soviet troops in. September 9th the 1944 Bulgarian coup d'état left the Bulgarian Communists in charge, where they’d stay until 1989. The wall fell on the 9th of November. Zhivkov stepped down the next day.

Bulgaria’s fate was determined on a napkin in Moscow, in a meeting between Stalin and Churchill, in what has come to be known as the percentages agreement, with Greece going to the West, Yugoslavia non aligned, 75% of Bulgaria going East. Such are politics.

In 1946, we became communist, said Steffano. Time to build communism. Secret police established with state security. Lots of surveillance, he tells us, showing us a door by a bar where people were interrogated. You didn’t want to be interrogated. The police made sure to know who was acting beyond official ideology, recruiting everyone to spy on everyone. Mass surveillance. Lots of espionage, look up the Bulgarian Umbrella, he says referring to a myriad of 1970’s era assassination attempts on activists, by the police, some with umbrellas that shot pellets like James Bond Movies.

The Russian model is still influential here, says Staffano. The Russian oligarchs are still supporting Russia, the invasion of Ukraine, opposing Europe, which most Bulgarians favor. When the new right wins seats, they celebrate at the Russian embassy here.

It's been complicated for a long time.

When the Germans burned the Reichstag in 1933, Hitler blamed the Communists. Our leader, Dimitrov, stood in Leipzig defending the communists. And gained a lifetime position, as head of the Communist Party. He dies in 1949 and is mummified, same doctor as Lennin. His mausoleum on Prince Alexander of Battenberg Square was built in six days, and destroyed in one, bombed in 1999, a relic of a repressive past we are still learning from.

In 1986, like every year, we had a May Manifestation. Yet, unlike other years, no leaders stood on the balcony across the street. No one was there waving to the parade. They knew something the crowd did not. Only a few days earlier on April 26th, the Chernobyl nuclear accident had left the air full of polluted rain, resulting in cancer, miscarriages, thousands sick, untold numbers dead. The Communists lost the trust of the people when they didn’t say anything. The officials knew it was happening. Information got to one level. People took iodine in Austria. No one knew here.

On the one hand, it was good, said Steffano. State funded education, state funded healthcare, zero unemployment, two years maternity leave.

The messy part is few seem to know how to reconcile the good and the bad of the era. There was no truth or reconciliation commission. We have public monuments, such as the mausoleum which was taken down. The nationalism which gripped other Balkan nations did not impact Bulgaria. The Russians are not seen as liberators here. We walked to the Soviet memorial to the liberation of Bulgaria from1954 celebrating the liberation ten years prior, when the Soviets rolled in. Few saw the Soviets as liberators then. And they do not see them as liberators of Ukraine now. On Feb 24, the anniversary of the war, people gathered and spoke out about the conflict. “Free Ukraine,” kids graffitied on the Soviet Memorial. In recent years, the memorial itself has become a canvas for various forms of dissent, rejecting notions of heroes or liberators. The kids were sent to jail. Thousands protested, bringing their own spray paint. How come we can, they asked the police. In 2014, when the conflict began between Russia and Ukraine the statue was painted with blue and yellow, the Ukraine colors. People express themselves here, says Steffano. He shows us photos of the graffiti used on the memorial through the years, pictures of the Soviet Star, now removed. There are many different paths. His grandparents came with flowers and saw them as liberators. Others protested and vandalized the monument. If there was just opposition, the statue would be gone, he concludes. Still the conversation over it grows:

“I would like to speak about life,” says Steffano, as our tour wraps up. Humans adapt to the systems around them. Many lived here, having normal lives, graduating from school. My mom graduated from school and was appointed to work in a small village as a teacher. They got a car and moved, when they had a baby. His grandfather loved it. It was limited and could be stifling. In 1989, his father went to West Berlin, got a TV and brought it back. He could have stayed, but he had a family and a life there. Still thousands disappeared, with executions. Muslims left. They felt unsafe, left for Turkey, averting a civil war.

Even after 1989, with free elections, the socialists still won. People still wanted jobs. They missed the good old days of bread and food and jobs. In 1997, we were on the verge of another revolution. We got together and made a plan, outlining a path to the future, joining NATO and the European Community.

Exhausted, Will and I thank Staffano and make our way for dinner.

I asked Wyatt for ideas.

“Haven’t been to Bulgaria in over 10 years but the Club of the Architect was a favorite secret spot” Wyatt wrote. “Drink rakia which is their moonshine, usually homemade and have a glass of ayran (yogurt, water and salt) next to it temper it. You’ll be super local with those two in hand.”

Well, he was right, a quiet reserved spot, it would be the best meal of the trip. And yes, the rakia was wonderful, so was the food in this quiet spot.

Paulina was our guide for the second day of the tour. She grew up in a ski resort in the Muslim town of Pomaki Bulgaria. She laughs when we tell her about the Communist Tour. Everyone yells at her if she says anything about that era.

‘Don’t say anything negative,’ they scream at me in the street.

Looking at conflict and history, it is useful to look back at bit. She starts with the Roman city here, established in the first century. They conquered the Thracian City, established after the Thracians first arrived in the peninsula, making their way toward what is now Bulgaria in the 6th century, BC. They migrated from Northern India to Europe, from Turkey, stopping along the way. This is the heart, the center of the Thracian Bulgarian Civilization. We have a Valley of Thracian kings, aristocrats and kings recognized by Ionesco. Romans came because of the abundance of springs, some 700 of them,

We are standing at St Nedelya, a church bombed by the Communists in April of 1925. 200 died, another 500 injured. A general had taken his granddaughter to church. They shot him. At his funeral at the church, they blew it up. It was rebuilt with a dome like the Hagia Sophia, in the Byzantine Style.

Beauty and violence, politics and vindication, building after building have similar stories to tell.

I’m trying to write as many of them as I can.

Paulina walks us toward the subway, to see the old ruins from Serdica, the Roman town from the first century. We know the amphitheater could hold 25,000 people. They were here for hundreds of years, at least 500 hundred, with the capital in Constantinople, instead of Sofia. It's still a sore subject that Sofia wasn’t picked. During the decline, things get complicated. One invasion after another, the Huns from 445-47, only here for a short time, before the Slaves. Bulgaria was founded in 681, by the Bulger and Slaves who arrived from Russia, with their own language, same origins. On we walk through the ruins of Serdica, in between the subway, built on the original Thracian town. One wave of people after another, the Ottomans arriving in 1386, starting with the Muslim influence, forbidding churches, transforming the country for the next 500 years. We stand at the East West main street of Serdica, says Paulina. By the 4th century, it was completely ruins, under the street.

At every turn, we zig and zag between histories. The communists closed the baths, says Paulina. She has lots to say about the communists. On we walk, talking about our tour and the city, past Roman ruins, to McDonalds, the subway. The city wasn’t liberated until 1878, by our brothers, the Russians, she says with sarcasm. On the 3rd of March, the Ottomans admitted defeat. Before, there were dozens of mosques. After liberation, they were mostly destroyed. Sofia became the capital. New infrastructure followed. Ottoman buildings removed. One of the two remaining mosques was right here, she says, looking at the market.

The topic turns to the current moment.

Is there tension?

Yes and no, says Paulina, standing in front of a Mosque from 1567. There are many refugees from Pakistan. We have a border with Turkey. Many refugees are coming every day. Smugglers bring immigrants every day. Some suffocated in a bus. The corruption at the border is too much. Europe said to us, deal with this. You can’t join the Shengen zone until you deal with it. They come from Syria through Turkey, to Bulgaria, to Serbia, Germany, and Austria. So, yes, there is tension. 12 or 13% of the population of Bulgaria is Muslim. Few are in Sofia.

The Romans built walls.

The Ottomans knocked them down.

Paulina starts down another controversy. There were 49,000 Jews here before World War II. Today, 2,000. Bulgaria did not send the Jew away, says Paulina (at least not from here. We hear another story in Macedonia). Our Jews will not leave, said our leaders. They will not be rounded up and sent to the police. They were asked to move to the country. Our king visited Hitler in 1943. Came home and died two weeks later. Apparently, he’d been poisoned. Sophia was bombed by the British in 1943. The Soviets took over in 1944 and started nationalizing everything; everyone lost everything. And in 1947, the remaining Jews left for Israel.

Walking, we make our way to the old Via Miliarius. @byzantinemporia explain: "Built by the Romans in the 1st c. AD to secure the Balkans, it ran from the Danube through Thrace to the future site of Constantinople. Many armies would march along it in both directions throughout Byzantine history." Today, the road leads from Venice to Srebrenica to Zabrag to Belgrad to Niche to Sophia Plodiv to Edine to Adriana, and Istanbol, 26 hours by car. It was a trading post from Dubrovnik to to Split to Sophia, says Paulina.

It's already been a few hours, we’ve been walking.

I ask about how she retells this history, the choices she takes.

History is history. I cannot change it, Paulina says. I smile. Well, sometimes I go in one direction, she confesses, emphasizing, Vasil Levski, a Bulgarian revolutionary. He was poor. He organized resistance. He gave the belief in liberation. One thing or another. We can talk about resistance fighters who helped us believe we could be independent. We could talk about poets, Ivan Vazov, Under the Yolk, who gave us richness, or Khristo Botev, close friend of Votilevsk, who wrote about soldiers, shot on the second of June. At noon sirens go off, we stop what we are doing, to remember. “To love with hate and passion,” said Botev, channeling a national revolutionary fervor. “I met each one of our national heroes and came to the conclusion that the big guys do small things, while the small people contribute to the biggest things.” Every tour is a different version of history, says Paulina. We can talk about Constantinople, residents of emperors, Constantine born in Nich, close to here. It was his motherland. He decided to cut the empire in half. East and West, a city on the Bosphorus, East side of the empire. He proclaimed this new capital, gave it a name. Constantanople, the West Rome. It hurt Sofia. It declined. Sofia is not Paris. 75% of the city was bombed during World War II. It would have looked like Praha.

Summer 1989, 350,000 muslims left for Turkey. June, the Communists opened the border. People left their jobs, fleeing to Turkey. By August, Turkey had had enough. The borders opened again in November 1989. Today, many of those who left still have duel citizenship.

By hour four of our conversation, we’re all over the place.

The topic turns to the Soviet Memorial.

“People are brain washed. The Russians liberated what?” asks Paulina, sarcastically. “The population is very pro Russian. They think what you see on TV is lies. That Russia liberated Ukraine.”

As it's gone all afternoon, we have to move backward to understand the current moment.

“In Bulgaria, they hoped it would be better in 1944 when the Soviets came. Yet, by 1946, the high society was shot. First of February shot, We have a memorial day for those who were shot.”

It's a cruel history here, Churchill dividing up our region. He hated Bulgaria, but he loved the wine.

Next stop, St Sophia, an Eastern Orthodox church, the site of several older churches, from the the 4th or 5th Century by the Romans, giving the name to the town.

Over the years, most were demolished by the invading armies of Goths and the Huns, Roman tombs from the second century below.

Outside a Memorial for Ivan Vazoff and the war dead, "Bulgaria, for you they died."

Across the street, we walk to our final stop, the Alexander Nevsky, a Neo Byzantine, Orthodox cathedral built on a Roman Church, for the Bulgarians who fought for independence, in 1877 -8.

It's a majestic space.

An old monk sneers at most of us inside.

And we keep on talking about the Balkan wars, one after another after liberation from the Ottomans. Paulina shows us where King Ferdinand sat with his son who saved the Jews here, and sister who fought for independence.

The myths are everywhere here.

Go to the National Museum, she advises. I’ll call you a cab, says Paulina, running off to meet her kids. We make our way to the 1973 Communist era building, turned museum in 2000.

All afternoon, stories of continue, but Will and I are slap happy, half able to process, the archaeology. An elder tour guide takes us through her tour of the pre Thracian people who disappeared, leaving spoons and objects. And Homer who told stories about the Thracian people who settled here in the Odyssey. She doesn’t take us through the images of the uprising after 1877, stopping at the statue of Vasil Levski, strategist of the movement for liberation, captured and hung. Successors finished his work in 1878, before still more Balkan wars, 1912-13, splits, conflicts, conquests, empires one after another.

Will and I find our way to a local brew pub. Everyone is happy to help us figure out the next steps of the journey to Belgrad, etc. Our heads are spinning, thinking about the Wonderful day touring through Sofia, for hours and hours. Through mosques, temples, empires, and thousands of years of histories and cultures. Walking home, I keep seeing the old trams moving through the city filled with trees and graffiti.

And think of those passing along along the way.

On the road, we had two losses, Uncle Mike, brother of Bruce, as well as Wayne Shorter.

Chris wrote about Mike:

“Lighting a candle tonight in honor of my Uncle Mike, who passed away in recent days from Parkinson's disease.

William Ireland Westcott - who went by Michael, was born in February 1937 and raised in Doylestown, PA. Uncle Mike was the identical twin of my father Bruce Westcott, and lived the majority of his years in San Francisco where he worked as a psychiatrist. Mike was a Vietnam War veteran, who moved to SF in the early 1970s where he came into his own in the city's "gay in the military" scene of the time. Mike was a lover of ballet, organ music, and the Paul Taylor dance company. He spent his vacation's scuba diving and exploring his love for the ocean. He grieved the loss of many of his dear ones during the AIDS epidemic that rocked SF in the 1980s, and was known for his candor, dry-humor, kindness, and love of wearing all things purple .

Uncle Mike played an important role in my life as a child, even though he lived at a distance. Mike was the first out gay person I encountered. I sensed that he was living his truth, even when the cloud of his grief was heavy and palpable. Uncle Mike opened his home to me, and helped me settle in San Francisco when I moved there from Thailand in my early 20s. It was during these years that I would hear more of his stories and know his kindness & hospitality from up close.

Holding you in the light tonight Uncle Mike! Thankful for the truthfulness you demonstrated to me and my family, grateful for the time we shared. May you rest in peace and dignity.”

Wayne Shorter followed.

Such a poet...

A poet of sound. Thank you for thousands of wonderful moments and feelings... Together ...

I correspond with Al about it all, about Wayne and Jaco and Weather Report.

“I met him when jaco first joined Weather Report in 1974. Jaco was staying with us at the time and playing in blood sweat and tears for a minute until he joined weather report.

Ben Maurer says: “Incredible....please check out the rolling stones how can I stop, he plays on that song.”

This blog is for them.

Its for everyone who shared of themselves, who shared their stories, and their complicated lives.

We are just one country in and the trip is only amping up.

No comments:

Post a Comment