“In Spain, the dead are more alive than the dead of any other country in the world,” said Federico Garcia Lorca. I felt them hiking past burial grounds for the civil war dead, along the Camino de Santiago, talking with other hikers about the conflicts. Some of the hikers I meet remember the end of Franco, the lost uncle, the brother tortured for a weekend, the grandfather detained, the brother disappeared during that clash of ideologies, Nationalists favoring Catholic traditions and Republicans in favor of liberal democracy, separation of church and state, and women’s rights. It's a cruel moment when neighbors turn on neighbors. Yet, it happens again and again. I always wondered what happened as we walked past little town after little town. Old ladies sat quietly, looking into the distance. But few I met wanted to talk about it. All the while the country was unearthing remains of those killed, the disappeared, the mysteries of their departures extending back decades, those unofficial casualties of history. The Lost Generation of Children, robbed from their parents, in jail or on the run, kidnapped, separated, placed with Nationalist families as a tool of assimilation, still remained a mystery.

“It's quite a trauma,” said Will, our guide, standing in front of the Plaza de España, a square in central Madrid, Quixote looking at us in the distance. I told him about the conversations I'd had on the road. He told me about a man he met, whose father had been killed by Franco’s Falangists. It was a small town. He had to grow up there. And live with them, without being able to ever saying a word.

Will explained: “The Spanish Civil War is considered the darkest period in the modern history of the country.” We would be learning about the people who fought in it. We’d start at the location of the assault on the Montaña barracks, the siege that marked the beginning of the war on the democratically elected republic, in the iconic Temple of Debod, strolling to the Parque del Oeste, where the Battle of Ciudad Universitaria, raged in July 1936. From there, Will would lead us “see monuments that show evidence of the battle and commemorate the soldiers, artists, and writers who left an eternal impact on Spain's heritage.”

It all started for Will in the East End of London. He found himself fixated with a mural declaring, “No pasarán” depicting a riot between fascists and antifascists during the Battle of Cable Street of 4 October 1936. Who shall not pass, Will wondered. What was it that was happening?

“Fascism is always rising,” said the man to my left.

My cousin thinks the US will become a banana republic in the next five years.

What can we learn from Spain? The stories are worth exploring here. Rattled with conflict, it's a story that reminds of what might become of us.

It all started with the elections in February 1936, yet some say even earlier, perhaps 1934, says Will, with a deep British accent. The Republicans were elected and ready to govern the new republic, with women in the health ministry, one reform after another, legalizing abortions, education, banning marriage and sex work, advancing education, and generally modernizing a country that still felt very much like a feudal landscape unchanged. Led by Franco, the Nationalists were not so happy about the state of affairs. They favored Catholic doctrine and military hierarchy, not this secular state, not armies run by civil government.

This clash escalated quickly, with assassinations, uprisings crushed, round ups, executions. Franco led with a fury of White Terror, instilling fear, learned in his years leading the Spanish protectorate in Morocco, crushing the will of the people there. White Terror vs Red, Will does not apologize for what the Republicans did. No one is innocent in war, even the good wars, WWII, etc. Still the White, Franco’s mass killings, were terrifying and brutal.

The Republicans maintained their popular front with the socialists, trade unionists, syndicalists, Bolsheviks, communists, and even anarchists, with the US and UK staying officially neutral in the conflict. Still, Will points out, the British bankers had no problem financially supporting the Nationalists. Roosevelt gave the nod to Texaco to do business with the Nationalists, who already enjoyed the support of Ford and IBM, as well as the Nazis. IBM, of course, denies they aided the Nazis. Yet, they never sued any of the historians who made these claims.

George Orwell called his country of Britain’s neutrality “pro fascist”. He also put his friends' names on lists for the government, I quip. Will nods. He called out others for the righteous fist waving, Will adds, ever doing it himself. Still everyone was playing their angles, international support rolling in. Hemingway says the Nationalists have taken over, in a bit of propagandist prose. He was a bit of a diva, says Will, mythmaking about the conflict.

On we walk from site to site, tracing the defense of Madrid from Franco’s onslaught. In May of ‘37, Guernica was bombed. Franco bragged he’d rather see Madrid destroyed than controlled by the Socialists. Airstrikes were constant. Yet, they strengthen the resolve of the troops. And Madrid becomes a sort of rallying point around Europe, with supporters coming to join the Popular Front. The anarchists want revolution. The Socialists just want to win. Stalin maintains his support, his purges beginning to the East. The Abe Lincoln Brigade, a desegregated US brigade, sees a parallel in their cause. Paul Robeson sings for the troops. Supporters arrive, writers and poets; John Des Passos and Hemingway witness it first hand, sending in their dispatches.

The Durutti Column were an anarchist military unit named after Buenaventura Durruti, who’d robbed banks for the poor, organized the Barcelona underground with Los Solidarios. The Anarcho Syndicalists were a little confused about how to support free love, says Will, noting the marriage ban was not received well. Active from 18 July 1936 to 28 April 1937, the Durruti Column, came to be a symbol of the movement and its efforts to fashion an egalitarian society. Still the socialists organized to win. They often clashed with the revolutionary anarchists in their own sort of brewing civil civil war. A master organizer, Durutti was eventually shot, some say by the Anarchist Republicans, others charge the Communists. And some think he shot himself. No one really knows.

On we walk, stopping at a statue of Simon Bolivar.

The words “Traiter, liar,” are painted below.

Spain was demoralized after the Spanish American War, Will reminds us. And the US is only beginning its imperial ambitions.

Observing the debacle, Mark Twain quipped, "We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. . . It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.”

With the Civil War only escalating. Refugees made their way north, across the Pyrenees, to France.

The battle raged, each side vying for Madrid. The Italians supported the Nationalists sending in tanks in the rain, clashing with the Garibaldi Brigade of Italian Socialists, in the distance, one raid after another. The Nationalists and Republicans dug in trenches, throwing food, taunting each other, about who had more supplies.

All the while, Hemingway was meeting troops and other journalists at La Vinicia, his favorite bar, where even now, there are signs saying no photographs of recordings are permitted. Still spies were rounded up there.

General Mola, the Nationalist general in charge of the north, suggested four columns of troops would take Madrid. They’d be joined by a Fifth Column, of traitors lurking inside the movement, those with sympathies to the Nationalist cause.

Cracks were beginning to show in the Popular Front, anarchists battling anarchists, internal civil war within the civil war. Lack of leadership was the death knell of the Republic, says Will, with irreconcilable differences by May of 1937.

Hitler annexed the Sudetenland, with Chamberlain’s “peace in our time” the 30th of September 1938. Stalin’s troops eventually left, disengaging from the Civil War. And Franco moved forward. The will to fight was crumbling among Republicans. The National Defence Committee eventually folded. The next year, Franco could declare victory.

The partisans joined battlefronts elsewhere in the war, Enrique Lister as far as Stalingrad.

Fleeing repercussions, some half a million Spanish refugees traveled North to France, over the Pyrenees, in 1939 where they were detained and eventually rounded up by the Nazis, perishing. No one is exactly sure how many. But possibly half a million made the crossing. Some joined the war effort. Many more were sent to internment camps. The French got amnesty. There’s not much historic memory in this regard, says Will. It's usually blocked. There's a lack of nuance on this stuff. But the Democratic Memory Law finally passed in 2007. Graves are being excavated, including the mass graves here, where the dead are being identified. This fight to remember extends from grave to grave, town to town, lost family member after lost family member. There is still much to figure out. What happened with the stolen generation, Will wonders, the Lost Children of Francoism. What of the hospitals, who said the kids were dead, when they were passed from Republican Families to Nationalist Families, while parents languished in prisons or interrogation. And all progressive Francis can do is offer an apology, says Will, referring to the pope, who has his own history in Argentina to attend to.

Juan Carlos appointed a plebiscite in 1978, favoring a constitutional democracy, with decisions made by an elected Prime Minister, like the UK. Amnesty follows; memories are buried.

It's not easy to figure out how to reconcile these civil wars or their lessons. We certainly did not in the US. Well, Ulysses Grant did send in the troops against the Klan, says Will. But the Klan is still alive and the Black Panthers were decimated.

The Nazi’s learned a lot from the US racism and apartheid, says Will. The Nazi Lebensraum, or Living Space, was inspired by the US concept of Manifest Destiny, used to justify slaughtering the indigenous population. There wasn’t much apologizing in the US. German companies are still paying reparations for their role in the war. The US has its prison industrial complex and if any one says anything, they are called woke. Reconstruction was a mixed legacy, says Will. There were seven states that had forced sterilization until the 1970’s.

Other refugees took boats from Spain after the war, some as far as Latin America, many landing in Chile, where they settled. A generation later, they were forced to contend with Pinochet. Many fled back, where because of Amnesty, they were welcomed. Many got asylum. Isabel Allende's novel "A Long Petal of the Sea" traces their voyage.

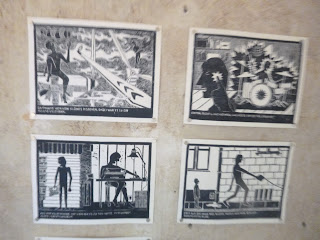

The Republic left a long legacy, says Will concluding things. The priority was education, an emphasis on the arts, on poetry, to build a better society.

Standing in front of the memorial for Miguel Hernandez, Will reads:

“This is a city not placated with fire

This laurel is not cut with rancor,

This rose bush without fortune.

This lavender exhales jubilation.”

It wasn’t for naught, says Will. Back through the the Parque del Oeste, I find myself walking, looking at the beautiful city, strolling through its history. A woman sits typing under the statue of Quixote, the master, down the street from the Prado. Kids are meeting for dinner, paella and tapas, sangria and beer pouring.

My friend Allan Moore and I catch up to talk about Spain where he now lives. “I”m totally an outsider,” he confessed. “But the Civil War, it leaves a massive wound. There was amnesty for the fascists. No one had to pay restitution for properties taken, for lives lost. In the US nobody forgot who was robbed or killed. There has to be a general recognition of this for the betrayals,” says Allan, referring to the long history of friends turning on friends, dating back to Plymouth rock and the first Pilgrim Thanksgiving, when indigenous people are said to have helped the Pilgrims plant. In return, an epidemic and betrayal after betrayal.

“In Spain, the right are coming back and saying Cortez was a hero for bringing Christianity,” said Moore. “For a long time, nothing was said. That came from fascism, when those who spoke up were jailed or watched their kids kicked out of school. So people didn’t talk. That hasn’t been a problem in the US, well not since the 1950’s. In Spain, it's slowly changing. There is more of a reckoning in South America.”

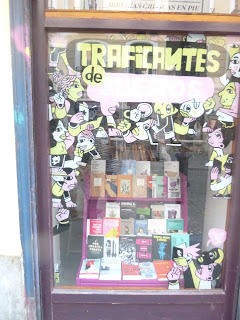

His words echo through my mind as I walk through the hot afternoon, after the tour, first back to the Prado, and then to Tirso de Molina to see Traficantes bookstore, following his instructions to go to Mercado San Fernando. Said Allan: “ if you go to Tirso you are in Lavapies. That's the "alternative" neighborhood. Drift down to Plaza Nelson Mandela (watch out for drug dealer muggers; it's a thing now). And continue to Mercado San Fernando. That's the coolest public market.”

People are going to the theater, and book readings, or sitting outside, enjoying the sun, meeting at cafes. Sitting having a beer, I hear some music. Kids are going to and from what looks like an old social center called La Tabacalera Madrid, an art center in the old tobacco factory with installations, street art, exhibitions. Inside, walls are filled with murals and graffiti. Marching bands are rehearsing. Some guys are playing reggae music. Others are painting murals. A band is playing drums.They sell me a beer for nothing. And we all hang out, dancing through the early evening, before I find my way back to my hostel. Hot sexy Madrid is always in motion, well into the evening.

Memories of our old Madrid trips dance in my mind. I think about hiking on the way here, staying with the family here, all those years ago, stopping in Madrid after a week in magic time on the trail, ever wondering, dreaming, and then back to the mad modern world of Madrid, where we ate sushi and chocolate. The kids are now grown, Caroline on a boat in the UK, Dodi in LA, getting ready to come to Berlin, Bear in the Czech Republic. Another friend from New York is sending me dispatches about what to eat here. My Sangria and paella are wonderful.

“The civil war is a deep social issue that for many people there is still unresolved,” says another old friend from New York. “I have too much to say about Madrid.” He mentioned Almovedar referring to the taboo subject in his new film Parallel Mothers.

“Janis is around 40, lives in Madrid and is a successful commercial photographer. She was named after Janis Joplin by her hippie mother . When she photographs forensic anthropologist Arturo for a magazine, she asks him for help with a family matter. Her great-grandfather was murdered by Falangists during the Spanish Civil War and buried in a mass grave near her family's home village. Arturo works for a foundation dedicated to investigating the crimes of the Franco regime , run by the conservative government in Madrid under Mariano Rajoy but doesn't get any funding for it. Arturo reports to Janis a few days later that regional authorities are likely to step in as donors. If permission is granted for the exhumation , he will direct the work. Janis' family and other villagers have collected a lot of information about the village's fate during the civil war and in the years since. They hope that the remains can be identified so that they can be buried with dignity in the family graves in the village cemetery…. Months later, the exhumation of the victims of the Franco regime begins in a field not far from Janis' home village… The last shot shows those who were shot lying in the mass grave before it was filled up.”

Parallel Mothers ends with this quote: "There is no silent history. However much they burn it, however much they smash it, however much they lie about it, human history refuses to shut up.”

Back in Berlin, the stories of international solidarity extend in countless directions.

I correspond with my old college roommate, telling him about my trip to Madrid.

“The civil war is still all around us here,” says Hank, who now lives in Catalonia. “On a future trip you should check out Portbou, the last (or first, depending on your perspective) town in Spain, near the french border. It's where Walter Benjamin commited suicide after being refused entry. It's a beautiful spot and still filled with the energy of that period.”

“He’s a huge influence for us all, even today,” I reply.

“He keeps coming up in our lives too. Lots of threads, and so tragic that he ended it so soon, when he probably could have crossed. Our town snitch died last year. He was almost 100. He had been an antique dealer and had several warehouses full of decaying furniture. When we first moved here we'd visit him every so often to get more furnishings for our house. On the 3rd or 4th visit he asked us if we wanted to see he his "barroom." We said sure. He lead is into another space, behind several locks and padlocks. Inside was a bar decorated with fascists regalia and memorabilia, including several portraits of Franco and a photograph of Franco and the old King, Juan Carlos. "This is how things were in the good old days." He said to us, smiling. As we got to know more people we learned that Zepo, his nickname, had been the guy that would inform on his neighbors, if he heard them saying critical things about the regime. By this time, the 50's or 60's, people weren't being disappeared anymore, but you might get passed over for that promotion if you were thought of as unsympathetic to the government. Every house in our town has a secret room where people would hide if they need to. At the top of our town, in a neighborhood known as The Castle (because there had been a Moorish and then Templar castle until the 18th century), there was a plaque commemorating the quartering of Italian troops. I'm not sure when the plaque had been put up, but obviously sometime before Franco's death. At some point in the last decade the Spanish and Catalan governments passed laws allowing for the removal of Franco-era monuments. A few months after we moved here, with no ceremony, the plaque was finally removed.”

Some stories can’t go on the record, as some divides are still left here, he tells me.

“Another funny story is that there is an imposing women here. She's physically big and all the foreigners are scared of her. She's bossy and shouts a lot. She's nicknamed "the Colonel." Nicknames here are inherited. Our electrician is called "Chispa" which means "Sparky." His father and grandfather were also electricians and and also known as "Chispa." The story goes that the Colonel's grandmother had had an affair with a Colonel in Franco's army, hence the nickname.”

Back at school, some days our discussions involve colonial legacies and divided cities, Audre Lorde in Berlin , transnational friendships, movements, grabbing a coffee after class at my favorite coffee shop, seeing a sign that reminded us we have had presidents who connected with other places, inspiring. Kennedy seems to follow us, from Dallas to Berlin.

Later, we find ourselves people walking around Koti, and seeing electronic noise at Loophole. And then off to silver future, a cool queer bar, talking about it all...pride from Berlin to Brooklyn and back.

All the while, the teenagers were making their way back to town. With mermaids rising and dreamscapes moving, living theaters converging in Paris and Bloomsbury day ending, one club closed, another popping, I found myself at Kater Blau dancing away the afternoon with new buddies from Mexico, and countless places in between, feeling grateful to be here, the sun making its way through the crowd, with house pumping, one kid in Czech Republic, another in Los Angeles, Caroline in Belfast, while I danced in Berlin. There are few better ways to spend an afternoon.

That night, the teenager arrived from the Czech Republic. The next day, the older one made a drop by, fresh from the city of angels, via a three hour layover at JFK, ready for a summer in Berlin. The next day Caroline arrived. We spend days exploring the neighborhood, checking out the demos and show coming up, enjoying the summer.

“In Spain, the dead are more alive than the dead of any other country in the world,” said Federico Garcia Lorca. I felt them hiking past burial grounds for the civil war dead, along the Camino de Santiago, talking with other hikers about the conflicts. Some of the hikers I meet remember the end of Franco, the lost uncle, the brother tortured for a weekend, the grandfather detained, the brother disappeared during that clash of ideologies, Nationalists favoring Catholic traditions and Republicans in favor of liberal democracy, separation of church and state, and women’s rights. It's a cruel moment when neighbors turn on neighbors. Yet, it happens again and again. I always wondered what happened as we walked past little town after little town. Old ladies sat quietly, looking into the distance. But few I met wanted to talk about it. All the while the country was unearthing remains of those killed, the disappeared, the mysteries of their departures extending back decades, those unofficial casualties of history. The Lost Generation of Children, robbed from their parents, in jail or on the run, kidnapped, separated, placed with Nationalist families as a tool of assimilation, still remained a mystery.

“It's quite a trauma,” said Will, our guide, standing in front of the Plaza de España, a square in central Madrid, Quixote looking at us in the distance. I told him about the conversations I'd had on the road. He told me about a man he met, whose father had been killed by Franco’s Falangists. It was a small town. He had to grow up there. And live with them, without being able to ever saying a word.

Will explained: “The Spanish Civil War is considered the darkest period in the modern history of the country.” We would be learning about the people who fought in it. We’d start at the location of the assault on the Montaña barracks, the siege that marked the beginning of the war on the democratically elected republic, in the iconic Temple of Debod, strolling to the Parque del Oeste, where the Battle of Ciudad Universitaria, raged in July 1936. From there, Will would lead us “see monuments that show evidence of the battle and commemorate the soldiers, artists, and writers who left an eternal impact on Spain's heritage.”

It all started for Will in the East End of London. He found himself fixated with a mural declaring, “No pasarán” depicting a riot between fascists and antifascists during the Battle of Cable Street of 4 October 1936. Who shall not pass, Will wondered. What was it that was happening?

“Fascism is always rising,” said the man to my left.

My cousin thinks the US will become a banana republic in the next five years.

What can we learn from Spain? The stories are worth exploring here. Rattled with conflict, it's a story that reminds of what might become of us.

It all started with the elections in February 1936, yet some say even earlier, perhaps 1934, says Will, with a deep British accent. The Republicans were elected and ready to govern the new republic, with women in the health ministry, one reform after another, legalizing abortions, education, banning marriage and sex work, advancing education, and generally modernizing a country that still felt very much like a feudal landscape unchanged. Led by Franco, the Nationalists were not so happy about the state of affairs. They favored Catholic doctrine and military hierarchy, not this secular state, not armies run by civil government.

This clash escalated quickly, with assassinations, uprisings crushed, round ups, executions. Franco led with a fury of White Terror, instilling fear, learned in his years leading the Spanish protectorate in Morocco, crushing the will of the people there. White Terror vs Red, Will does not apologize for what the Republicans did. No one is innocent in war, even the good wars, WWII, etc. Still the White, Franco’s mass killings, were terrifying and brutal.

The Republicans maintained their popular front with the socialists, trade unionists, syndicalists, Bolsheviks, communists, and even anarchists, with the US and UK staying officially neutral in the conflict. Still, Will points out, the British bankers had no problem financially supporting the Nationalists. Roosevelt gave the nod to Texaco to do business with the Nationalists, who already enjoyed the support of Ford and IBM, as well as the Nazis. IBM, of course, denies they aided the Nazis. Yet, they never sued any of the historians who made these claims.

George Orwell called his country of Britain’s neutrality “pro fascist”. He also put his friends' names on lists for the government, I quip. Will nods. He called out others for the righteous fist waving, Will adds, ever doing it himself. Still everyone was playing their angles, international support rolling in. Hemingway says the Nationalists have taken over, in a bit of propagandist prose. He was a bit of a diva, says Will, mythmaking about the conflict.

On we walk from site to site, tracing the defense of Madrid from Franco’s onslaught. In May of ‘37, Guernica was bombed. Franco bragged he’d rather see Madrid destroyed than controlled by the Socialists. Airstrikes were constant. Yet, they strengthen the resolve of the troops. And Madrid becomes a sort of rallying point around Europe, with supporters coming to join the Popular Front. The anarchists want revolution. The Socialists just want to win. Stalin maintains his support, his purges beginning to the East. The Abe Lincoln Brigade, a desegregated US brigade, sees a parallel in their cause. Paul Robeson sings for the troops. Supporters arrive, writers and poets; John Des Passos and Hemingway witness it first hand, sending in their dispatches.

The Durutti Column were an anarchist military unit named after Buenaventura Durruti, who’d robbed banks for the poor, organized the Barcelona underground with Los Solidarios. The Anarcho Syndicalists were a little confused about how to support free love, says Will, noting the marriage ban was not received well. Active from 18 July 1936 to 28 April 1937, the Durruti Column, came to be a symbol of the movement and its efforts to fashion an egalitarian society. Still the socialists organized to win. They often clashed with the revolutionary anarchists in their own sort of brewing civil civil war. A master organizer, Durutti was eventually shot, some say by the Anarchist Republicans, others charge the Communists. And some think he shot himself. No one really knows.

On we walk, stopping at a statue of Simon Bolivar.

The words “Traiter, liar,” are painted below.

Spain was demoralized after the Spanish American War, Will reminds us. And the US is only beginning its imperial ambitions.

Observing the debacle, Mark Twain quipped, "We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. . . It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.”

With the Civil War only escalating. Refugees made their way north, across the Pyrenees, to France.

The battle raged, each side vying for Madrid. The Italians supported the Nationalists sending in tanks in the rain, clashing with the Garibaldi Brigade of Italian Socialists, in the distance, one raid after another. The Nationalists and Republicans dug in trenches, throwing food, taunting each other, about who had more supplies.

All the while, Hemingway was meeting troops and other journalists at La Vinicia, his favorite bar, where even now, there are signs saying no photographs of recordings are permitted. Still spies were rounded up there.

General Mola, the Nationalist general in charge of the north, suggested four columns of troops would take Madrid. They’d be joined by a Fifth Column, of traitors lurking inside the movement, those with sympathies to the Nationalist cause.

Cracks were beginning to show in the Popular Front, anarchists battling anarchists, internal civil war within the civil war. Lack of leadership was the death knell of the Republic, says Will, with irreconcilable differences by May of 1937.

Hitler annexed the Sudetenland, with Chamberlain’s “peace in our time” the 30th of September 1938. Stalin’s troops eventually left, disengaging from the Civil War. And Franco moved forward. The will to fight was crumbling among Republicans. The National Defence Committee eventually folded. The next year, Franco could declare victory.

The partisans joined battlefronts elsewhere in the war, Enrique Lister as far as Stalingrad.

Fleeing repercussions, some half a million Spanish refugees traveled North to France, over the Pyrenees, in 1939 where they were detained and eventually rounded up by the Nazis, perishing. No one is exactly sure how many. But possibly half a million made the crossing. Some joined the war effort. Many more were sent to internment camps. The French got amnesty. There’s not much historic memory in this regard, says Will. It's usually blocked. There's a lack of nuance on this stuff. But the Democratic Memory Law finally passed in 2007. Graves are being excavated, including the mass graves here, where the dead are being identified. This fight to remember extends from grave to grave, town to town, lost family member after lost family member. There is still much to figure out. What happened with the stolen generation, Will wonders, the Lost Children of Francoism. What of the hospitals, who said the kids were dead, when they were passed from Republican Families to Nationalist Families, while parents languished in prisons or interrogation. And all progressive Francis can do is offer an apology, says Will, referring to the pope, who has his own history in Argentina to attend to.

Juan Carlos appointed a plebiscite in 1978, favoring a constitutional democracy, with decisions made by an elected Prime Minister, like the UK. Amnesty follows; memories are buried.

It's not easy to figure out how to reconcile these civil wars or their lessons. We certainly did not in the US. Well, Ulysses Grant did send in the troops against the Klan, says Will. But the Klan is still alive and the Black Panthers were decimated.

The Nazi’s learned a lot from the US racism and apartheid, says Will. The Nazi Lebensraum, or Living Space, was inspired by the US concept of Manifest Destiny, used to justify slaughtering the indigenous population. There wasn’t much apologizing in the US. German companies are still paying reparations for their role in the war. The US has its prison industrial complex and if any one says anything, they are called woke. Reconstruction was a mixed legacy, says Will. There were seven states that had forced sterilization until the 1970’s.

Other refugees took boats from Spain after the war, some as far as Latin America, many landing in Chile, where they settled. A generation later, they were forced to contend with Pinochet. Many fled back, where because of Amnesty, they were welcomed. Many got asylum. Isabel Allende's novel "A Long Petal of the Sea" traces their voyage.

The Republic left a long legacy, says Will concluding things. The priority was education, an emphasis on the arts, on poetry, to build a better society.

Standing in front of the memorial for Miguel Hernandez, Will reads:

“This is a city not placated with fire

This laurel is not cut with rancor,

This rose bush without fortune.

This lavender exhales jubilation.”

It wasn’t for naught, says Will. Back through the the Parque del Oeste, I find myself walking, looking at the beautiful city, strolling through its history. A woman sits typing under the statue of Quixote, the master, down the street from the Prado. Kids are meeting for dinner, paella and tapas, sangria and beer pouring.

My friend Allan Moore and I catch up to talk about Spain where he now lives. “I”m totally an outsider,” he confessed. “But the Civil War, it leaves a massive wound. There was amnesty for the fascists. No one had to pay restitution for properties taken, for lives lost. In the US nobody forgot who was robbed or killed. There has to be a general recognition of this for the betrayals,” says Allan, referring to the long history of friends turning on friends, dating back to Plymouth rock and the first Pilgrim Thanksgiving, when indigenous people are said to have helped the Pilgrims plant. In return, an epidemic and betrayal after betrayal.

“In Spain, the right are coming back and saying Cortez was a hero for bringing Christianity,” said Moore. “For a long time, nothing was said. That came from fascism, when those who spoke up were jailed or watched their kids kicked out of school. So people didn’t talk. That hasn’t been a problem in the US, well not since the 1950’s. In Spain, it's slowly changing. There is more of a reckoning in South America.”

His words echo through my mind as I walk through the hot afternoon, after the tour, first back to the Prado, and then to Tirso de Molina to see Traficantes bookstore, following his instructions to go to Mercado San Fernando. Said Allan: “ if you go to Tirso you are in Lavapies. That's the "alternative" neighborhood. Drift down to Plaza Nelson Mandela (watch out for drug dealer muggers; it's a thing now). And continue to Mercado San Fernando. That's the coolest public market.”

People are going to the theater, and book readings, or sitting outside, enjoying the sun, meeting at cafes. Sitting having a beer, I hear some music. Kids are going to and from what looks like an old social center called La Tabacalera Madrid, an art center in the old tobacco factory with installations, street art, exhibitions. Inside, walls are filled with murals and graffiti. Marching bands are rehearsing. Some guys are playing reggae music. Others are painting murals. A band is playing drums.They sell me a beer for nothing. And we all hang out, dancing through the early evening, before I find my way back to my hostel. Hot sexy Madrid is always in motion, well into the evening.

Memories of our old Madrid trips dance in my mind. I think about hiking on the way here, staying with the family here, all those years ago, stopping in Madrid after a week in magic time on the trail, ever wondering, dreaming, and then back to the mad modern world of Madrid, where we ate sushi and chocolate. The kids are now grown, Caroline on a boat in the UK, Dodi in LA, getting ready to come to Berlin, Bear in the Czech Republic. Another friend from New York is sending me dispatches about what to eat here. My Sangria and paella are wonderful.

“The civil war is a deep social issue that for many people there is still unresolved,” says another old friend from New York. “I have too much to say about Madrid.” He mentioned Almovedar referring to the taboo subject in his new film Parallel Mothers.

“Janis is around 40, lives in Madrid and is a successful commercial photographer. She was named after Janis Joplin by her hippie mother . When she photographs forensic anthropologist Arturo for a magazine, she asks him for help with a family matter. Her great-grandfather was murdered by Falangists during the Spanish Civil War and buried in a mass grave near her family's home village. Arturo works for a foundation dedicated to investigating the crimes of the Franco regime , run by the conservative government in Madrid under Mariano Rajoy but doesn't get any funding for it. Arturo reports to Janis a few days later that regional authorities are likely to step in as donors. If permission is granted for the exhumation , he will direct the work. Janis' family and other villagers have collected a lot of information about the village's fate during the civil war and in the years since. They hope that the remains can be identified so that they can be buried with dignity in the family graves in the village cemetery…. Months later, the exhumation of the victims of the Franco regime begins in a field not far from Janis' home village… The last shot shows those who were shot lying in the mass grave before it was filled up.”

Parallel Mothers ends with this quote: "There is no silent history. However much they burn it, however much they smash it, however much they lie about it, human history refuses to shut up.”

Back in Berlin, the stories of international solidarity extend in countless directions.

I correspond with my old college roommate, telling him about my trip to Madrid.

“The civil war is still all around us here,” says Hank, who now lives in Catalonia. “On a future trip you should check out Portbou, the last (or first, depending on your perspective) town in Spain, near the french border. It's where Walter Benjamin commited suicide after being refused entry. It's a beautiful spot and still filled with the energy of that period.”

“He’s a huge influence for us all, even today,” I reply.

“He keeps coming up in our lives too. Lots of threads, and so tragic that he ended it so soon, when he probably could have crossed. Our town snitch died last year. He was almost 100. He had been an antique dealer and had several warehouses full of decaying furniture. When we first moved here we'd visit him every so often to get more furnishings for our house. On the 3rd or 4th visit he asked us if we wanted to see he his "barroom." We said sure. He lead is into another space, behind several locks and padlocks. Inside was a bar decorated with fascists regalia and memorabilia, including several portraits of Franco and a photograph of Franco and the old King, Juan Carlos. "This is how things were in the good old days." He said to us, smiling. As we got to know more people we learned that Zepo, his nickname, had been the guy that would inform on his neighbors, if he heard them saying critical things about the regime. By this time, the 50's or 60's, people weren't being disappeared anymore, but you might get passed over for that promotion if you were thought of as unsympathetic to the government. Every house in our town has a secret room where people would hide if they need to. At the top of our town, in a neighborhood known as The Castle (because there had been a Moorish and then Templar castle until the 18th century), there was a plaque commemorating the quartering of Italian troops. I'm not sure when the plaque had been put up, but obviously sometime before Franco's death. At some point in the last decade the Spanish and Catalan governments passed laws allowing for the removal of Franco-era monuments. A few months after we moved here, with no ceremony, the plaque was finally removed.”

Some stories can’t go on the record, as some divides are still left here, he tells me.

“Another funny story is that there is an imposing women here. She's physically big and all the foreigners are scared of her. She's bossy and shouts a lot. She's nicknamed "the Colonel." Nicknames here are inherited. Our electrician is called "Chispa" which means "Sparky." His father and grandfather were also electricians and and also known as "Chispa." The story goes that the Colonel's grandmother had had an affair with a Colonel in Franco's army, hence the nickname.”

Back at school, some days our discussions involve colonial legacies and divided cities, Audre Lorde in Berlin , transnational friendships, movements, grabbing a coffee after class at my favorite coffee shop, seeing a sign that reminded us we have had presidents who connected with other places, inspiring. Kennedy seems to follow us, from Dallas to Berlin.

Later, we find ourselves people walking around Koti, and seeing electronic noise at Loophole. And then off to silver future, a cool queer bar, talking about it all...pride from Berlin to Brooklyn and back.

All the while, the teenagers were making their way back to town. With mermaids rising and dreamscapes moving, living theaters converging in Paris and Bloomsbury day ending, one club closed, another popping, I found myself at Kater Blau dancing away the afternoon with new buddies from Mexico, and countless places in between, feeling grateful to be here, the sun making its way through the crowd, with house pumping, one kid in Czech Republic, another in Los Angeles, Caroline in Belfast, while I danced in Berlin. There are few better ways to spend an afternoon.

That night, the teenager arrived from the Czech Republic. The next day, the older one made a drop by, fresh from the city of angels, via a three hour layover at JFK, ready for a summer in Berlin. The next day Caroline arrived. We spend days exploring the neighborhood, checking out the demos and show coming up, enjoying the summer.

No comments:

Post a Comment