|

| Nina Simone and Stolen Kisses |

|

| Collage by Nicolas Lampert by mlk. |

“Bowie is promiscuous - religiously” – these were the words on the bulletin

at Judson on Sunday.

The whole congregation sang, “Ch ch changes…” all of us channeling Bowie together. And it felt great. We sang and wondered all morning, finishing with “We Shall

Overcome…” Thinking about Pete and MLK and our struggles with ourselves and the climate, the

words hit me in a striking way.

Later, we listened to Nina.

She speaks to all us struggling and hoping.

I Wish I Knew How It

Would Feel to Be Free

I wish I knew how

It would feel to be free

I wish I could break

All the chains holdin' me

I wish I could say

All the things that I should say

Say 'em loud say 'em clear

For the whole 'round world to hear

It would feel to be free

I wish I could break

All the chains holdin' me

I wish I could say

All the things that I should say

Say 'em loud say 'em clear

For the whole 'round world to hear

I wish I could share

All the love that's in my heart

Remove all the bars

That keep us apart

I wish you could know

What it means to be me

Then you'd see and agree

That every man should be free

All the love that's in my heart

Remove all the bars

That keep us apart

I wish you could know

What it means to be me

Then you'd see and agree

That every man should be free

I wish I could give

All I'm longin' to give

I wish I could live like I'm longing to live

I wish I could do all the things that I can do

And though I'm way over due

I'd be startin' a new

All I'm longin' to give

I wish I could live like I'm longing to live

I wish I could do all the things that I can do

And though I'm way over due

I'd be startin' a new

Well I wish I could be

Like a bird in the sky

How sweet it would be

If I found I could fly

Oh I'd soar to the sun

And look down at the sea

Like a bird in the sky

How sweet it would be

If I found I could fly

Oh I'd soar to the sun

And look down at the sea

I told Aaron at the video

store about watching Jean Genet au chant d amour at the house.

“Did you know that ‘Gene

Genie’ was Jean Genet? We’re gonna keep unpacking Bowie's gift for years to

come.

So true. Good friends stay with us as we meander

through these memories and cultural artifacts.

I spend the week,

finishing Sustainable Urbanism, my new book, due in a week. Its been an amazing

inner journey to recall all the stories and finish it, really amazing.

The history of

dialectical materialism takes us in amazing places. I've re read Rilke and Hardt and Negri, old Constituent Imagination book all week.

So I wrote all week,

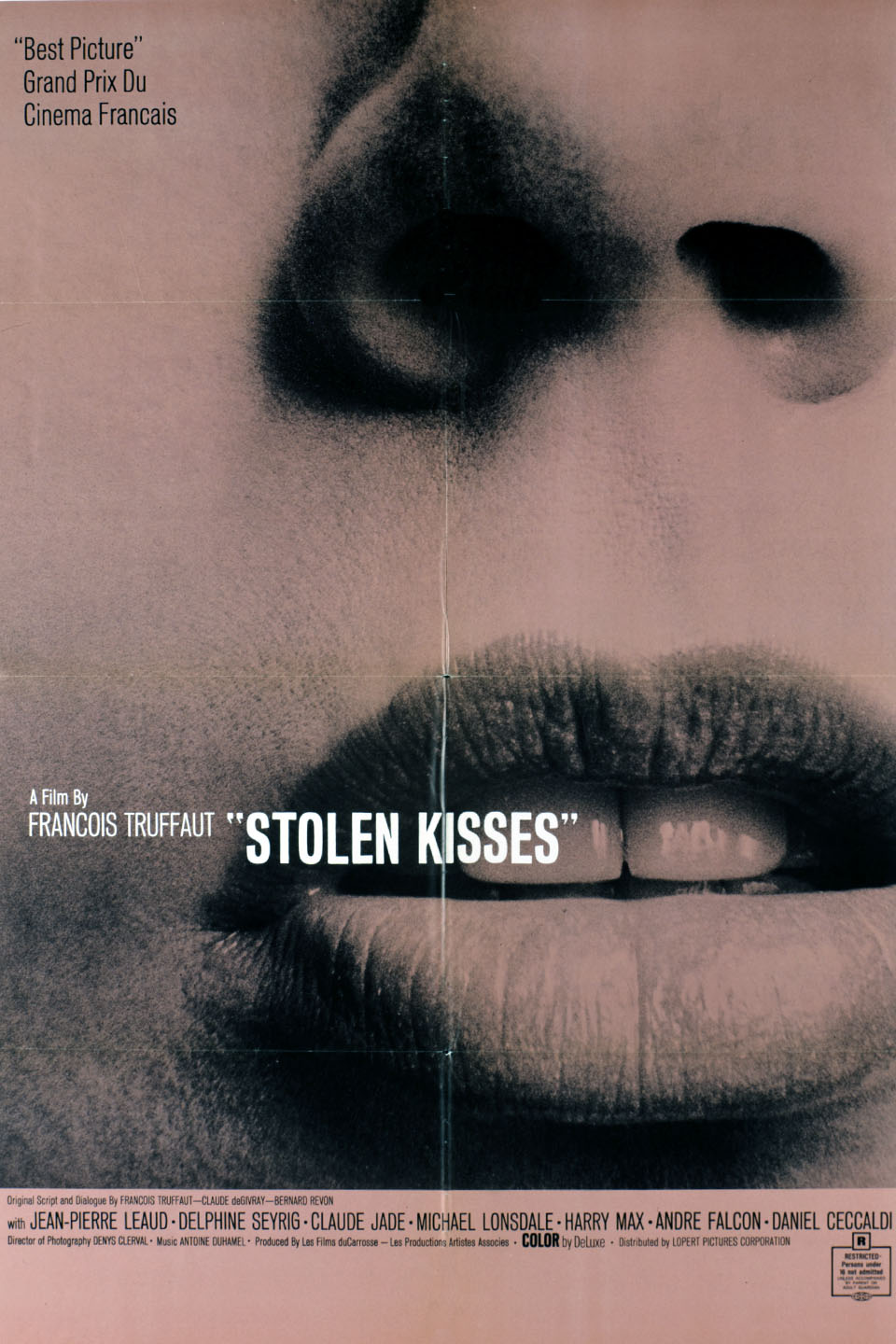

watched the girls roller derby, ran around Washington Square and East Harlem and rode home, where we watched old movies and stolen kisses by Truffaut, Stolen Kisses and the debate. I snapped a few shots. "She awoke in us the spring of luminous sexuality," the adolescent boys recall.

Later we watched the debate. I'm still sure if i should #feeltheburn or jump on the Clinton bandwagon. Ghosts of McGovern haunt me.

We need good people to nominate good judges. Last week, a friend told me about Judy helping push back the DA hellbent on going after him, hell bent on releasing all his old arrest records. Her story shines. "Those arrests she didn't happen," she declared, unwilling to open the old records.

Later, we visited Garrison, where we listened to Nina. Judy’s candle is still burning there. It will be for a long time.

A blog asked me to

send them something about Rebel Friendships and arrange for another reading at

the Commons on March 14th.

On Rebel Friendships by

Benjamin Shepard

“We need rebel friendships, not Facebook friends” noted long time activist John Jordan during a Facebook discussion about the internet and activism. His point, of course, was that authentic friends help us connect in ways social networks rarely can. The intersections between individual and community, the ways we experiment, explore, create, fight back alienation, and reduce the harms of modern living, this is the stuff of social movements (Nardi, 1999). Yet, does it help or hinder democratic living and civil society? This question is a little messier.

Political friendship requires we engage a messy space between our public and private selves, pulling those we care about into an engagement with the larger world (Rawlins, 2009). This is part of what Aristotle might have been wondering when he suggested that true friends must enjoy more than mutual pleasure or benefit; they must also be engaged in larger efforts for the society, with friendship supporting civil society and democratic living (Bellah and company, 1985, Doyle and Smith, 2002). This is not a dynamic one finds in institutions or governments. So, people are turning to friendships which support a wide variety of range of experiments in living. The question is how? How do friendships help us change the world and what happens when they break down? These are the questions which run through this small book.

Today,

cohorts of people the world over are striving to create a better life through

the process of collective engagement. From

bike rides to community gardening, groups of friends are disrobing alienating

social relations in favor of gestures of affect, care, and connection. Each forms a sort of “pocket of resistance” suggests

Sub Commondante Marcos. And they are

multiplying. “Each has its own history,

its specificalities, its similarities, its demands, its struggles, its

successes. If humanity wants to survive

and improve, its only hope resides in these pockets made up of the excluded, of

those left for dead, of the disposable,” argues Marcos (Merrified,

2011,xvi). Through this collective

striving, regular people the world over are reframing of the politics of

everyday living, electing themselves and their friends into their own own

imaginary parties. Here collective action,

affective bonds and convivial social relations are favored over institutional

social arrangements, as collectives of friends strive for a common path to

realize dreams beyond the state, social class or party affiliation (Merrifield,

p. 2011, xvi, p. 64-5). Instead of

looking to elected officials, they aspire to a “blurrry, still unrealized realm

of global friendship,” viewed as an asset and extension of their efforts (Merrifield

2011, p. 132). Through these rebel

friendships, regular people support social relations disencumbered from

competition (invisible committee, 2009). Such

friendship help regular people to realize non antagonistic social relations

outside of capitalism or arrangements in which one party benefits at the

expense of others, as some improve their lot by stepping on others. The practice of rebel friendship reminds us

of other ways of living and being (Holt, 2015).

This is not to

suggest that the politics of friendship is

simple or represents some sort of substitution for effort or organization.

“[M]aking friends equally requires perseverance and certain patience, taking

time to get to know each other, to enter genuine dialogue, talking as well as

listening,”

notes Merrifield (2011, p. 133). Like

family, these engagements contain their own messy, often contradictory

approaches to love, care and egalitarian social relations. Here the blurry

links between love, friendship,

and social movements animating efforts aimed toward social change. Friendship informs social movements, infusing them with the social

capital necessary to move bodies of ideas.

Such innovation is rarely witnessed in formalized social arrangements,

few of which today’s social movement participants seem interested in joining

anyway.

At their core, Gerald Suttles (1970) suggests friendships are social relations that can exist with various social strata or social groups. By their very nature, they lend themselves toward deviance. “The logic of friendship is a simple social transformation of the rules of public propriety to their opposite,” explains Suttles (1970, p.96). Friends can touch each other where others cannot. Friends can swear or become exceptionally pious around one another. Friends can entertain certain utopian notions that would be laughed at in public circumstances,” (Suttles, 1970, p.96).

As the nexus between individual and community, friendship glues the social capital necessary for organizing (Nardi 1999). Yet when people think of friendships and their links with social movements, theories regarding social networks, weak ties, collective identity, and fluidarity tend to come to mind (Juris, 2008; McDonald, 2002). The problem with these theories, of course, is they leave us flat, rarely coming close to the feeling of working with a group of friends—the trust and solidarity, care, tensions and joy of connection with a group of people one comes to know and spend time with as if they were a surrogate family.

Throughout the social movements from anarchist autonomous movements to Gay Liberation, the Settlement Houses Movement to the Beats, ACT UP to Occupy, public space to environmental justice, one can trace a story of friendships coming together, supporting bountiful mages of beauty and justice, as well as a few quarrels

After

all, friendships impact social movements in multiple ways. A review of the meanings of friendship helps

us trace a means for individuals to connect their lives and feelings with

social forces which impact their lives.

It helps scholars of social movements come to grips with both means for

supporting civil society and social capital, as well as a generational turn

away from political parties toward affinity groups of friends which has rarely

been part of discussions social

movements. Here, a consideration of

friendship helps us expand on the very nature of what is political and how that

connects individuals with questions about participation. It adds an affective dimension to discussions

of social networks and movement participation, as well as understandings of

“emotions” in politics (Gould, 2002, Goodwin et al, 2001). A politics of friendship builds on the

recognition that that “interpersonal emotional realities” are part of

organizing; they are “directly, simultaneously connected to the community work

being carried out” (Burghardt 1982, p. 26). Here, rambunctious engagement between

friends opens up new spaces and scripts for individuals and groups, allowing

those involved to find new thngs about themselves along the way. We grow and evolve in relationship with

others after all (Mead, 1963). People

must be allowed to grow personally and emotionally if they are to succeed in

organizing (much anything else in life).

Such scholarship moves away from cold calculations of resources and

analysis of costs and benefits, favoring the meanings, practices, and lived

experience of those involved within the of efforts to create change (Jasper

1998, p. 26). Movements are built on

countless meanings few of which are adequately explained within

institutionalist perspectives. By the

1960s, this attitude began to shift. Movement scholars and activists began to

rethink when and why and how activists got involved and to what end. Many of the newer approaches to movement

scholarship stand in stark contrast to dominant approaches to social movement

scholarship which emphasize rational choices, collective behavior, and

allocation of resources (Gould, 2002).

Still efforts to consider the politics of friendships have felt

neglected by social movement scholars.

Yet, this may be changing.

Perhaps just perhaps the time has come to take friendship seriously.

To create a new world

“Come, my friends,

It is not too late to seek a newer

world,” Alfred Tennyson writes in “Ulysses.”

Rebel friendships take us there, conjuring new worlds, taking hold in difficult times, when courage is

high and sometimes low.

Benjamin Shepard is leading a friendship on rebel

friendships and affinity groups at the Brooklyn Commons on March 14 at 730.

The Commons

388 Atlantic Avenue

Brooklyn, 11217

United States

388 Atlantic Avenue

Brooklyn, 11217

United States

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete