|

| A map of where we went, a kid, and a sign for Casa Gramsci. |

We woke up in Aleghro, the full haze of the day and the

night before making its way through our minds. I dreamed of taking Dad’s

old friend Fred on a boat. He’s been gone for over a quarter of a

century. But I knew him and so did Matteo. He wore a cowboy hat when

Matteo met him, shortly before Dad took Matteo to Big Bend National Park back

in 1987. But his memory lingers this morning, as does the day before, taking a

final stroll before continuing our journey South West, through Sardignia. We’ve

love Aleghro, the medieval winding streets, the water, the piazzas, the people,

the restaurants, our boat ride. So we meander through town again, looking at

the shops and streets, picking up a few souvenirs. And make our way onto the

wild road. Driving is never easy here. The streets are a tight, congested

game of chicken as drivers vie for space. Don’t panic, notes Caroline.

Its not panic as much as fear of making a one lane road work for two cars

careening in opposite directions. But eventually we make our way onto the

windy coastal roads. They remind me of Big Sur in California, the world

whirling in front of us, coasts of the bluest water to the right, trees and

nuraghe to the left.

The House

Its hard to imagine these mounds of rocks have been there

for thousands of years, megalithic edifices developed during a Nuragic Age

somewhere between 1900 and 730 BC. But there they are, just as you find such

mounds in Ireland and Mexico. The shape of time takes countless twists and

turns, just like the road here. I can’t look too long or I’ll drive the

car off the cliffs like in the movies. But this isn’t a movie.

Careening through the hills, we made our way towards the

Marina in the Bosa Province of Oristano Sardinia , stopping for a lovely

lunch. Caroline has eggplant parm. I go swimming.

And we keep on driving, snapping shots of nuraghe when we

can. So many more, disappeared without a shot. More and more trees, more

and more coasts, a few 2000 year old mounds here or there.

“Do you want to go to Grasci’s house?” Caroline asks. He’s

been a source of ridicule for Matteo, who hates the Communists

here. We have similar ambivalent feelings. But love the

Prison Notebooks and admire his thoughts on political praxis and

education.

“Yes. Is it here?”

“Yes… Its nearby.”

A useful reminder of what happens when fascists find their

way into power and intellectuals are jailed, we made our way to Ghilarza, where

the author of The Prison Notebooks, lived.

“Its like a Camino town,” noted the little one, as we

parked by the old church.

No one was on the streets. But a few cars were

parked. Storefronts closed. We walked into the old church and then walked

toward the museum.

Closed reads the sign.

It’ll be open in ten minutes.

So we walk around a bit, exploring the town.

“Aperto?” I ask a woman toward the museum.

“In ten minutes….”

Finally, she opens the doors and showed us around the

space, full of old newspapers, photos, drafts of all the prison notebooks that

he wrote as he passed his days for a decade before he died in 1937.

“odio gli indifferenti,” declared one t shirt, referring to his

old letter, meaning, “I

hate the indifferent. I believe that life

means taking sides. One who is really alive,can be

nothing if not citizen and partisan. Indifference is lethargy:

it is parasitism, not life. ...Indifference is the

dead weight of history. plays an important role in history.

It plays a passive role, but it does play a role. It is fatality; is is

something that can not be counted on; it is something that disrupts programs,

overturns the best made plans; it is that awful something that chokes

intelligence… What happens, the evil that touches everyone, happens

because the majority relinquish their will to it, allowing the enactment of

laws that only a revolution can revoke, letting men rise to power who, later,

only a mutiny can remove.

….”

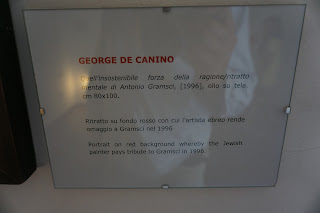

The museum displays portraits, as well as copies of the

author’s copy of the Divine Comedy. He wrote, he organized,

and he believed in our capacity to think, to believe in our own

intelligence. One of the

great joys of my life was reading the Prison Notebooks, Il

Quaderno, with Stanley Aronowitz, who wrote extensively about Gramsci in books

and essays including: “Gramsci’s Theory of Education: Schooling and Beyond”….

The last room of the museum was of the author writing in

prison.

It’s a chilling reminder that ideas are not always free.

There no happy endings here. But it less than a decade

after he perished, Gramsci’s tormentor, faced a similar fate.

In the history of movements, we fight, biker, anarchists

battle anarchists, fascists jail communists, who went onto jail countless

others after from 1945 till 1990. And the beat goes on as our president

meets with Putin. There are few happy endings here.

The House

The Antonio

Gramsci house is in the historic centre of Ghilarza, a city of about 4,500

residents in the mid-valley of the Tirso River in the Oristano Province, in the

historic and geographic sub-region of Guilcer.

Antonio Gramsci

lived here from the age of 7 to 20 years, 1898 to 1911. He was born in Ales, in

the Province of Cagliari, on 22 January 1891. After a few months, his family

moved to Sorgono and then to Ghilarza, the town his mother, Peppina Marcias,

was from. After elementary school, from 1905 to 1911, Antonio attended first

the junior secondary school at Santu Lussurgiu, then the senior secondary

school in Cagliari.

He would return

home often, from Santu Lussurgiu every Sunday and less frequently from Cagliari.

He always spent his summers at Ghilarza. At age 20, in the autumn of 1911, he

left for Turin, where he had been awarded a scholarship that allowed him to

attend the University, where he enrolled in the Faculty of Letters. He returned

again to Ghilarza during the summers of 1912 and 1913, and then for two short

visits in 1920 and 1924. From his move to Turin until the end of his life – he

died at 46 – he lived in furnished rooms, hotels, hospitals, pensions and jail

cells. This house in Ghilarza was the only real home he ever had.

The property was

then owned by Grazia Delogu, Antonio’s mother’s unmarried stepsister. During

his childhood and adolescence, ten people lived in this house: his aunt Grazia,

his father Francesco, his mother Peppina and the seven children: Gennaro,

Grazietta, Emma, Antonio, Mario, Teresina and Carlo.

The house was

built in the early years of the nineteenth century of basalt, a volcanic rock

often used in houses typical of central Sardinia. Of a simple and dignified

appearance, it consists of two storeys, with the only decorative element on the

front being the balcony and its wrought iron railings.

The interior,

which has been well preserved, has 6 bedrooms, 3 on the ground level and 3 on

the upper level, and is now used as a museum. The connection between the two

storeys is still a stairway in its initial position, and the series of rooms

remains almost entirely faithful to their original use as living quarters. In

the rear courtyard, which still has its cobblestones with flower beds marked

off with stones and tiles, there is a small building called the sa

‘omo ‘e su forru (the oven house).

Renovation

measures that were done over time did not much alter the structure of the

property, which as a whole has kept its original appearance.

The house, the

city of Ghilarza and the surrounding area were, for Antonio Gramsci, places

full of memory and affection to which he returned many times with notes of

aching homesickness. These environments were described in Letters from

Prison and Prison Notebooks or in the records by

his early biographers.

Sitting here in

Italy, where they have their own history of fascism, I see its always good to

be aware who your friends are. There are not always happy endings.

Leaving the

museum, we make our way to Agriturismo Casa Marmida outside of Guspini,

which will be our base for the next three nights. Full of sheep, pigs and farm

animals, a dog walking about, it’s provides some of the best food we’ve had

here. Our hosts are wonderful.

Spending our

nights eating on a country farm, our days boating between ancient cliffs and

grottoes, its not too bad here! We might want to stay here. We adore Sardinia!

No comments:

Post a Comment