In Occupy This Book, my friend Mickey Z suggests we spend more time thinking about trees. With gardens threatened from Harlem to Bed Stuy, this is a worth while endeavor.

DeBlasio's tale of

two cities is to allow the Lower East Side gardens to become permanent while

those in Harlem and Bed Stuy face the bulldozers to make way for luxury condos. Yet, there is another way to build a city. Green housing is not build on

green gardens. There

are countless other vacant lots to build upon. We need to push back against

this arrangement. Tuesday meet us at city hall at 9 am to fight to defend all the gardens.

Save all the gardens. SAVE OUR COMMUNITY GARDENS!

Join the New York City Community Garden Coalition &

Concerned New Yorkers for a Rally and Press Conference

On the Steps of City Hall (Manhattan) – Tuesday, February 10 at 9 a.m.

We are demanding that the mayor stop HPD from selling

17 active community gardens for development when

there are dozens of vacant lots that can be sold instead.

On the Steps of City Hall (Manhattan) – Tuesday, February 10 at 9 a.m.

We are demanding that the mayor stop HPD from selling

17 active community gardens for development when

there are dozens of vacant lots that can be sold instead.

UNITE WITH YOUR NEIGHBORS IN MAKING

ALL OUR COMMUNITY GARDENS PERMANENT!

ALL OUR COMMUNITY GARDENS PERMANENT!

Call Aziz: 973-222-5413 or email: eighty20group@gmail.com

THE NEXT LOT TO BE SOLD

MAY BE YOUR COMMUNITY GARDEN!

www.nyccgc.org

MAY BE YOUR COMMUNITY GARDEN!

www.nyccgc.org

We need to fight to protect all community gardens, while

making sure our distinct neighborhoods retain their character, their quicky selves, intact

for all to enjoy, not just the super rich.

Many are profoundly concerned that new development plans will

colonize their neighborhoods, with out of place buildings, furthering displacement and gentrification.

As my friend Apple Gray notes, quoting from a New

York Times report on the hyper

development plans for east new york:

“We see

what’s going on around in the city,” said Joyce Scott-Brayboy, 58, a community

board member and retired city worker in East New York. “No to that in East New

York. No. No.”

Hers is the first neighborhood Mayor Bill de Blasio’s

administration has chosen to grow under his affordable housing strategy, which

he has made one of his signature policy initiatives, and which he made the

centerpiece of his State of the City address on Tuesday. But Ms. Scott-Brayboy

is hardly alone in challenging his vision. Around the city, people who have

watched luxury buildings and wealthy newcomers remake their streets are balking

at the growth Mr. de Blasio envisions, saying that the influx of market-rate

apartments called for in the city’s plans could gut neighborhoods — not

preserve them.

Many have started to suggest that gentrification

is the new colonialism.

|

| Lois+Stavsky/Flickr |

There has to be another, more sustainable way of building

cities. Thinking about this challenge, trees offer us a clue.

Trees somehow remind us of another way of being and seeing, of honoring our history and its deep roots

in the earth. If we lose gardens, we lose spaces for new trees or age old ones,

trees that gave us shelter and fun, that helped us find solace in this concrete

jungle.

Over the last few months, this blog has more and more entries

about trees, more and more homage. In the fall of 2014, we grieved for the loss of the Bendy Tree in Tompkins Square park, connecting its story with the efforts of the People's Climate March to help us fashion a more sustainable urbanism.

|

| homage and memorial to the tompkins square park bendy tree. bottom two photos by Eric McGregor |

As Reverend Billy writes:

I drop of Lena at school at 5th and B and walk to the East Village’s heart, Tompkins Square Park, and walk to where Bendy lived for 130 years. She is the tree that bowed to the east horizontally, about a human head’s height from the ground before rising with her leaves waving in the wind. Through some bribe or something the beloved tree was chain-sawed last fall. The Parks Dept claimed falsely that she would fall on someone soon. But her branches were full of leaves, not a dead branch anywhere. In fact her bent jog in the air was her genius, her claim on our community self. Charley Parker and Allen Ginsberg and other very odd greats lived nearby. Anyway, the only possible autopsy was the murder of Bendy, which they did, and sure enough she was not rotten inside at all. Read more at: http://www.revbilly.com/bendy_trees_ear

Trees open a way of contending with a dialectic of modern living forcing us to contend with tensions between nature and urban space, trees and cities, gardens and private spaces, public commons and neoliberal encroachments.

I drop of Lena at school at 5th and B and walk to the East Village’s heart, Tompkins Square Park, and walk to where Bendy lived for 130 years. She is the tree that bowed to the east horizontally, about a human head’s height from the ground before rising with her leaves waving in the wind. Through some bribe or something the beloved tree was chain-sawed last fall. The Parks Dept claimed falsely that she would fall on someone soon. But her branches were full of leaves, not a dead branch anywhere. In fact her bent jog in the air was her genius, her claim on our community self. Charley Parker and Allen Ginsberg and other very odd greats lived nearby. Anyway, the only possible autopsy was the murder of Bendy, which they did, and sure enough she was not rotten inside at all. Read more at: http://www.revbilly.com/bendy_trees_ear

Trees open a way of contending with a dialectic of modern living forcing us to contend with tensions between nature and urban space, trees and cities, gardens and private spaces, public commons and neoliberal encroachments.

And sometimes these

things clash. When a tree was in the way

of a potential highway in Claremont Road, in

East London, a group of people organized to defend the 350 year old chestnut tree slated to be destroyed to make

way for a freeway.

John Jordan recalled the

tree and the courageous people who started a movement:

And for me, it was an

absolute moment made of up stories and beautiful acts. The whole campaign began

with an absolutely beautiful act. There was a tree on the common, and it was a

350-year-old chestnut tree. And we were told it wasn’t going to be knocked

down. And of course, as it turns out it was going to be knocked down. And the

parks department boarded it up. One day we decided to have a tree-enclosing

ceremony. And we opened up the space. And all these kids went down and pulled

the boards off and reoccupied the tree. And they actually built a tree house.

This was a first here. And of course this had been happening on the West Coast of

America with Earth First! but it had never happened here. And the papers wrote

about the tree house. And lots of people wrote letters. When the postman

arrived with letters, they had marked the address to the ‘tree house.’ And the

postman [treated] ‘tree house’ as an official address. And lawyers on hand

realized that once the place had a letter box and an address, then it become an

official dwelling place and could therefore be categorized as a squat. Then the

whole process of evicting it would have to go through court. So there was a

beautiful combination of collective creativity, with group creativity, with

people writing letters, lawyer creativity. We then created this model of tree

house that grew throughout several years. I really got involved as we got into

the way of machinery; people got into the way of the cranes. For me it was

actually very performative. For months and months and months, the arts and

crafts and performances really held off the construction of the road. And it

cost them hundreds and hundred of thousands of more pounds then they would have

spent before the tree was actually bulldozed.

|

| scenes from claremond road |

The

following campaign involved a struggle against the encroachment of the

state. 45 houses, from which a whole

neighborhood had been evicted, were to be bulldozed. In All

That Is Solid Melts into Air, Marshall Berman (1982) writes about watching

his entire neighborhood in the Bronx razed. The chapter that is not included in

this monumental story is what might have happened if the neighborhood members

had imagined ways to stay and defy the bulldozers. Yet this is what the

citizens of Claremont Road did when they squatted 45 houses there. People from around the world were drawn to

the campaign.

Lesley J. Wood, a Canadian activist who for many years was part of New York City’s Direct Action Network, witnessed the Claremont Road blockade.

Lesley J. Wood, a Canadian activist who for many years was part of New York City’s Direct Action Network, witnessed the Claremont Road blockade.

I went to England in

1993-94... There was a road blockade in the far East End of London. A whole row

of houses had been taken over in order to protest this new highway going

through a poor area. And some of the original residents stayed in their homes

on Claremont Road. It was a place which was friggin’ magical. They had nets

strung over the trees and across the houses.

The English have been cutting down trees for a long

time. They colonized Ireland by cutting

trees, deforesting Ireland. extracting resources while separating people from communities. “At that time the English occupiers cut down most of Ireland's

oak to use in shipbuilding and barrel making.”

The Druids worshiped under

those trees. So the attack on the trees was an attack on their culture.

The story of trees and cultures extends around the globe. People the world over find inspiration from them. They always have.

The story of trees and cultures extends around the globe. People the world over find inspiration from them. They always have.

Anne Frank saw the tree outside her window a source

of nourishment and connection to something larger than herself, connecting her small life to nature and

love, beauty and the divine, courage and care.

Trees can be symbols of generativity, care and support, as we see in Shel Silverstein's The Giving Tree. The tree gives the boy everything in the story. And in the end is the only thing the boy ever has or knows or can lean on.

Trees can be symbols of generativity, care and support, as we see in Shel Silverstein's The Giving Tree. The tree gives the boy everything in the story. And in the end is the only thing the boy ever has or knows or can lean on.

For Silverstein, the trees are an allegory of what happens when we take more than we give back.

They are also symbols of what happens when something horrible, such as the Nazis, grows out of control. That was the lesson the Little Prince saw in the baobab trees, growing from bad seeds on his little planet.

Yet, there are any number of ways to see them.

Over the years, trees became emblematic of the

tension between development and nature, between an integrated urbanism and

blandified space. They can also symbolize the resilience of cities.

The end of Betty Smith’s A Tree grows n Brooklyn suggests that we are more capable

of adapting to the urban environment than any of us could imagine. We can find ways of surviving and sharing

space as the tree and its supporters do in Williamsburg, reflecting in awe, as kids grow up along with an old tree:

“She

looked across the yards and saw that Florry was still staring at her through

the bars of the fire escape. Francie

waved and called:

“Hello,

Francie.”

“My

name ain’t Francie,” the little girl yelled back. “Its florry, and you know it too.”

“I

know,” said Francie.

She

looked down into the yard. The tree

whose leaf umbrellas had curled around, under and over her fire escape had been

cut down because the housewives complained that wash on the lines got entangled

in its branches. The landlord had sent

two men and they had chopped it down.

But

the tree hadn’t died … it hadn’t died.

A

new tree had grown from the stump and its trunk had grown along the ground

until it reached a place where there were no wash lines above it. Then it had

started to grow toward the sky again.

Annie,

the fire tree that the Nolands had cherished with watering and manurings, had

long sickened and died. But this tree in the yard- this tree that men chopped

down…. This tree that they build a bonfire around, trying to burn up its stump

– this tree lived!

It

lived! And nothing could destroy

it.

Once

more she looked at Florry Wendy reading on the fire escape.

“Goodbye,

Francie,” she whispered.

She

closed the window.” (Smith, P. 430).

Hopefully, more and more trees can grown, expand,

take root, teach and support people here in Brooklyn. But for that to happen, we have to support places for them to grow and breathe.

When

I got involved with the global justice movement, I was inspired by the

connections people made between the Earth First struggle to preserve old growth

forests on the West Coast with East Coast struggles

to preserve community gardens.

Groups such as Lower East Side Collective and More Gardens and Times Up!

helped take the lead to fight for the gardens.

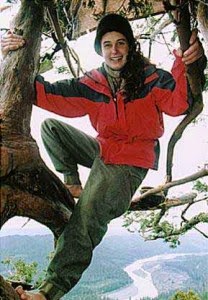

Many of us were blown away by Julia Butterfly Hill’s gesture

of courage.

For 738 days Julia Butterfly Hill lived in the canopy of an

ancient redwood tree, called Luna, to help make the world aware of the plight

of ancient forests. Her courageous act of civil disobedience gained

international attention for the redwoods as well as other environmental and

social justice issues and is chronicled in her book The Legacy of Luna: The

Story of a Tree, a Woman, and the Struggle to Save the Redwoods.

Julia, with the great help of steelworkers and environmentalists, successfully negotiated to permanently protect the 1,000 year-old tree and a nearly three- acre buffer zone. Her two-year vigil informed the public that only 3% of the ancient redwood forests remain and that the Headwaters Forest Agreement, brokered by state and federal agencies and Pacific Lumber/Maxxam Corporation, will not adequately protect forests and species.

On December 18, 1999 Julia Butterfly Hill, then 26, came down to a world that recognized her as a heroine and powerful voice for the environment. Her courage, commitment and profound clarity in articulating a message of hope, empowerment, and love and respect for all life has inspired millions of people worldwide.

“By standing together in unity, solidarity and love we will heal the wounds in the earth and in each other. We can make a positive difference through our actions"

Julia Hill chose the name Butterfly while in her childhood years and like her namesake she has undergone a great metamorphosis. She grew up in a deeply religious family as the daughter of a traveling, evangelical minister that later settled in Arkansas. In 1996 she suffered nearly fatal injuries in an auto accident. During close to a year of medical treatment and recovery, she had time to reassess her purpose in life. Two weeks after being released by her doctors, she headed west on a journey of self-discovery. She had no particular destination, but her first sight of the ancient redwoods overwhelmed her with awe.

“When I entered the majestic cathedral of the redwood forest for the first time, my spirit knew it had found what it was searching for. I dropped to my knees and began to cry because I was so overwhelmed by the wisdom, energy and spirituality housed in this holiest of temples"

Julia's brave and inspiring action brought international attention to the plight of our dwindling ancient redwoods. For many years after she returned to the ground, Julia toured the world speaking abour her experience in the media and to audiences large and small and about the many lessons she learned. She wrote a bestselling book, The Legacy of Luna, which is available in 11 languages, followed by her environmental "handbook", One Makes the Difference. Her story has inspired millions around the globe to take action in their own communities.

Julia, with the great help of steelworkers and environmentalists, successfully negotiated to permanently protect the 1,000 year-old tree and a nearly three- acre buffer zone. Her two-year vigil informed the public that only 3% of the ancient redwood forests remain and that the Headwaters Forest Agreement, brokered by state and federal agencies and Pacific Lumber/Maxxam Corporation, will not adequately protect forests and species.

On December 18, 1999 Julia Butterfly Hill, then 26, came down to a world that recognized her as a heroine and powerful voice for the environment. Her courage, commitment and profound clarity in articulating a message of hope, empowerment, and love and respect for all life has inspired millions of people worldwide.

“By standing together in unity, solidarity and love we will heal the wounds in the earth and in each other. We can make a positive difference through our actions"

Julia Hill chose the name Butterfly while in her childhood years and like her namesake she has undergone a great metamorphosis. She grew up in a deeply religious family as the daughter of a traveling, evangelical minister that later settled in Arkansas. In 1996 she suffered nearly fatal injuries in an auto accident. During close to a year of medical treatment and recovery, she had time to reassess her purpose in life. Two weeks after being released by her doctors, she headed west on a journey of self-discovery. She had no particular destination, but her first sight of the ancient redwoods overwhelmed her with awe.

“When I entered the majestic cathedral of the redwood forest for the first time, my spirit knew it had found what it was searching for. I dropped to my knees and began to cry because I was so overwhelmed by the wisdom, energy and spirituality housed in this holiest of temples"

Julia's brave and inspiring action brought international attention to the plight of our dwindling ancient redwoods. For many years after she returned to the ground, Julia toured the world speaking abour her experience in the media and to audiences large and small and about the many lessons she learned. She wrote a bestselling book, The Legacy of Luna, which is available in 11 languages, followed by her environmental "handbook", One Makes the Difference. Her story has inspired millions around the globe to take action in their own communities.

For years now, we’ve fought to preserve green spaces

in the urban environment, supporting Trees and Gardens, housing and open space

simultaneously. This is not a zero sum

argument.

Yet, we’ve lost a lot. Countless trees were lost after Sandy. And globally, we’ve lost so many giving

trees, and forests from the Amazon to the Pacific Northwest. When we lose a garden, we lose nature’s most

simple irrigation system, a place for water to drain and for oxygen to grow. A city facing the ravages of flooding could

do well to remember this.

Fortunately, today a tree planting culture is

growing in Canada and here in New York.

These are spaces where we see the world, enjoy nature,

they make us healthier people, more connected with ourselves and the

world.

"Warber and

co-author Kate Irvine, senior researcher of the Social, Economic, and

Geographical Sciences Research Group at the James Hutton Institute, in

Aberdeen, UK, recommend walking outside in nature at least three times a week

to experience benefits. Short, frequent jaunts are more beneficial…..”

Fortunately, New York has a few of its own cathedrals.

Fortunately, New York has a few of its own cathedrals.

I went to enjoy a few last Saturday, after a morning at a Bat Mitzvah at the Portuguese Spanish Synagogue, wondering

between the trees and majestic snow filled walking trails through Central Park,

winding East the Met, up to 96th street and back down to the Waldorf where my comrades

in ACT UP were busy zapping the HRC.

The trees of New York are

many; they are gyms. And we need more of

them. They are worth thinking about

and preserving.

|

| Scenes from a walk through the park, East to the Met, and back to join my friends in ACT UP for a street action. |

The best way to do so,

remind the city to make all the gardens permanent.

Join us Tuesday at

City Hall at 9 AM.

No comments:

Post a Comment