“’Tell you what,’ she said, looking at him. ‘You’re like Frankenstein but cute.’”

Rob Magnuson Smith,

“All Americans are lonely and lost. That’s why some of them come to England in

the first place,”

Rob Magnuson Smith, Scorper.

Rob and I were going to talk writing and life and the porous

line between lived experiences and words over the weekend. At least that was the plan as I made my way

out to Waterloo Station.

Ray Davies words’ echoed through my mind as I walked out from

the tube into the station to grab my train on my way south. Years and years of watching the video, I feel

like I am returning to a place I’ve seen before. Asking questions, “like why or

how or what am I doing it for?... will I reach my destination?”

Rob, our old friend from our San Francisco days, has always

been a part of this conversation. I

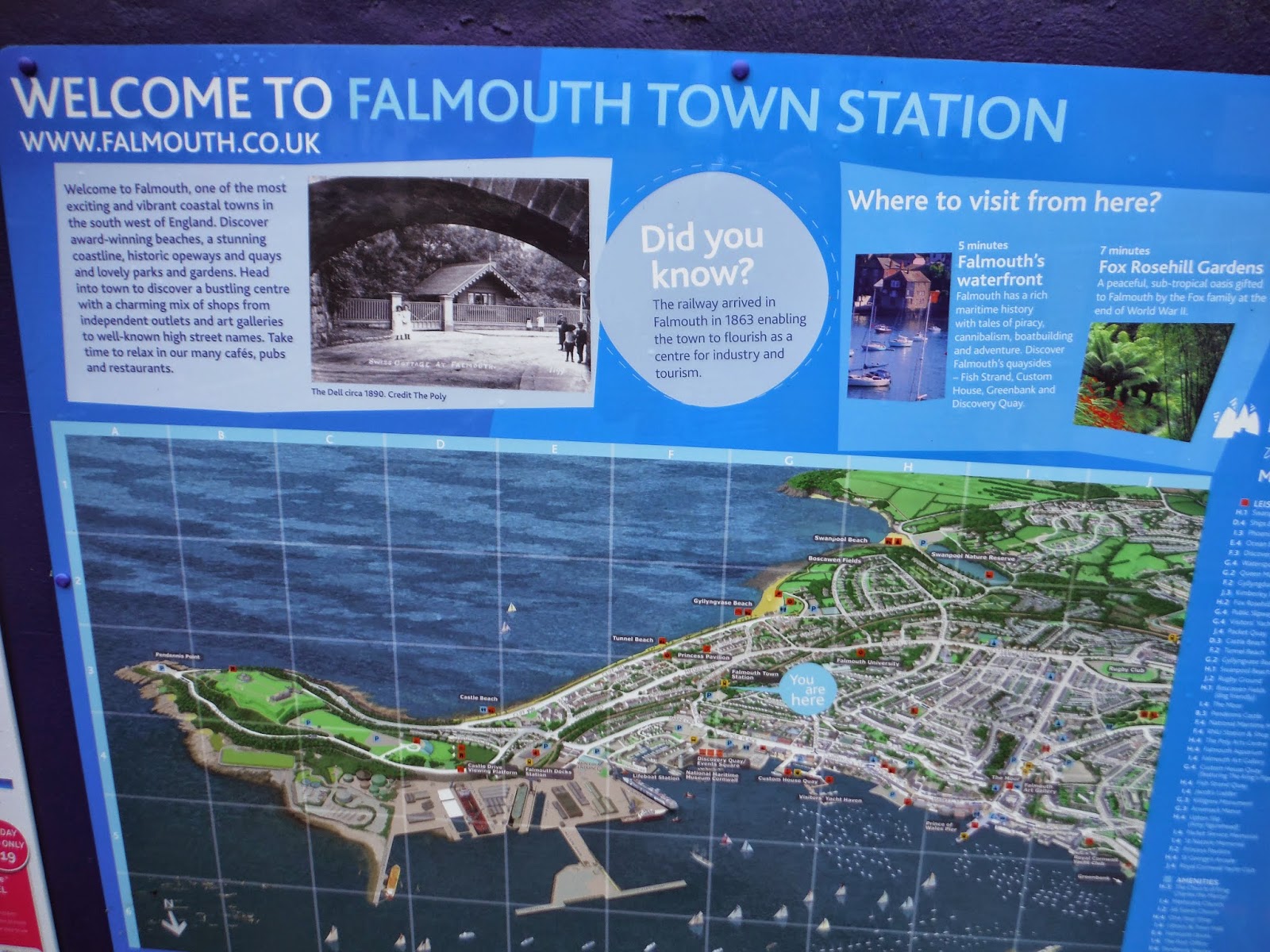

would journey most of the day to make my way to his new home in Falmouth, looking

out the window at the lush, increasingly bucolic landscape as our train made

its way. The outward journey from London

to Falmouth departed London Waterloo Station at 10:59. I would not make it there for another six

hours, arriving in Falmouth Town at 17:12 pm.

Passing the time, I chatted

with the woman sitting next to me as we made our way South for the bank holiday. We talked about New York and London, friends

and music. Her plan was to go surfing in Croyde, a surfing village where my new

friend planned to spend her next three months, in between with her apartments

in New York and London spoken for, rented, her life out of her mind. She drank wine, checked her messages, and chatted,

sharing restaurant tips and gossip about some of the musicians she works

for. And we both looked out the

window. Our minds somewhere far away.

By four PM, I made my connection in Truro, feeling the cold

mist in the air. It reminded me of the fog in San Francisco. This is always the case on the way to

Falmouth, on the sea in Cornwall, where so much of the lush vegetation, palm

trees, remind me of the California Rob and I both left behind. Those So Cal and San Francisco days were on my

mind all weekend long. Rob used to drive up his car from his beloved Los

Angeles multiple weekends a month when we both lived there two decades

prior. He’d arrive with Madonna

blasting from the tape player, quite often singing along. A light, easy going-ness

on his face, which age seems to have diminished on all of us today. Even then we had history. We had gotten out of school at Pitzer, in

Claremont, Ca, where we shared years of rambunctious goings on, bantered about

philosophy, romance, reproductive rights, affairs, monogamy, non monogamy, the

uses of literature, psychology and the movies.

Even then Rob was a fan of the classics, Russian novels and philosophy. He wasn’t a fan of the Rocky Horror Show, then

my favorite movie. Yet, today I show his favorite movie, One Flew over the Co

Co’s Next in my classes. I loved Rugby, history, and the links between pop

culture and my budding interest in writing and activism.

Through the years, we’d corresponded about his experiences

in the UK during his study abroad, alcohol and romance, women and the

aesthetics of the North East vs Southern California colleges, Pitzer vs Vassar college. A former girlfriend had lured me there,

leaving Rob to finish school out West at Pitzer. (Little did we imagine that he might teach

there, decades later). We didn’t set

foot on the campus again together. But the letters continued. After a

particularly nasty fight, I wrote him sitting on the patio at our farm in

Georgia. Rob’s stories about England and

some of those friends and enemies from those days, would find themselves into

his two novels The Gravedigger and Scorper.

As he told the BBC in an interview, it is impossible for a writer to

keep himself out completely. Novels are

about everything and nothing of who we are, simultaneously.

“Where is the oldest one in Falmouth?” I asked.

“Sadly, its gone. Someone poisoned it,” Rob informed me. “They wanted a better view.”

Falmouth is always a great place to reflect on the trees and

the messages they divine upon us, even in their absence.

What was the plan for the weekend? Nothing really. We could go to Penzance, where the pirates once cavorted, or visit friends of do nothing.

“Were you in Dorchester?” asked Rob, referring to the town

in Southern England where the Shepards are rumored to have hailed.

“Not this trip. There just wasn’t or time. We were too busy

being lost in London and Sheffield.”

Americans coming here “tracing…ancestors” would be a theme

of both our trips and stories, as well as his new novel.

“What in the world were you doing?...” notes the reflective,

second person narrator in Scorper. “This trip to England may be futile.”

But maybe not? I contend. The trip, the process is as important

as the outcome. That’s what counts. The reflection on the Kafkaesque new novel,

its narrative seeming to remind me of our trips to Prague and the Kafka museum

where neither of us felt quite well after a night of Absinthe as we

contemplated the master’s life out of balance in his limited radius there, the

bureaucratic rules entwining him, and the surrealist daydreams he used to elude

these social controls. That was until he

took himself out and the genius best friend disobeyed his request to throw his

manuscripts in the fire. Jorge Luis

Borges would describe his friend’s rejection of his ill-advised request as

perhaps the most heroic literary gesture of the 20th century. Yet, what do we do when our wounds are

self-inflicted, as Kafka’s were? What

happens when the trial of modern living, the rules of the castle are just too

much to bear?

Over the next two days, Rob and I retraced the steps and stories, trials and tributaries, between the pubs we’d visited the years before and the ways our lives had changed in the year to follow.

We sat in a local looking out at the town, watching the sun go down, enjoying a few pints, as the sea gulls danced in the distance. I was glad to be back to share the time and redemptive tragicominc story of his life, career, mine, and the line between our days in Southern California as undergraduate students almost three decades ago and our experiences today as academics, writing books and teaching and making sense of where life has taken us.

He showed me his new lovely home. We ate and made our way back out strolling down the hill.

“Its like the old walk back in LA,” I noted, reflecting on his old home in Silverlake, where we used to walk out into the Southern California night.

“There’s a California novel in you Rob. I just know it.”

Last year, we’d talked about my Dad and Rebel Friends, then

a work in progress. This year, we talked

how to finish the story.

“Every story grows out of a conflict,” he explained,

referring to Romeo and Juliet.

So what would this one be?

What would propel this story? Where

could the dialectic take this narrative?

And what would we become. Every

relationship takes a dialectical shape from formation, to conflict, to some

sort of resolution, at least hopefully. Of course, Rob is one of my age old

Rebel Friends, so this question resonates in countless ways.

Part of the fun of romping about Falmouth is meeting the

assorted cast of characters who drop by to say hello to Rob, as we visit his

locals. Abby, a local legend, plopped

herself down at our table. She’s been friends with most everyone here at one

point or another, still at it, making trouble for decades here.

We keep on walking to the Hand, where by this point, the

pubs take a groaning, ill-advised feeling.

We’ve all been out too long. And it’s starting to show.

Back at home, Rod and I gossip. The Morrissey Autobiography sitting at the table, he explains that the book

really was deserving of the title of Penguin Classic. I suggest it looks like someone is taking

care of Morrissey as he grins on the cover.

“Ben Shepard!” Rob declares the next morning, greeting the

day, as he mimics my old answering machine greeting.

He shows me his latest story in Playboy, posing in his

office for a shot. The austere office,

surrounded by books, looks just like the old one in LA where he first drafted

the Gravedigger.

“Maybe your Hollywood novel can be a variation on a

Narcissus and Goldman theme, with dopple gangers in Hollywood and England?"

Little do I know his new novel will take on a similar lost and found feeling, between here and there, and you really do not know in between.

Little do I know his new novel will take on a similar lost and found feeling, between here and there, and you really do not know in between.

We spend the day strolling.

Rob greets Nick, the proprietor from the Boat House.

“Good morning Nick!

You look so nice and clean shaven.”

“Well, 48 is the new 30,” Nick retorts thanking Rob for his

support.

“We’ll see you later tonight.”

Rob tells me about the Ethyl, the ghost who lives inside,

who hates the men who preside there.

She’s been haunting the men here, providing a for a swath of hard to

explain injuries since the 19th century, when she was thought to

have infected the men with a particularly virulent strain of the pox,

syphilis. So the angry sailors walled

her in, building bricks around her until she starved, buried alive. It was a common torture at the time noted

Rob.

An antique store is closing. So I drop in for a glimpse,

taking in the relics and junk.

“We had to make some decisions,” explained one of the

workers.

“This one is really good,” he notes, nodding at the old

picture I’ve picked up, giving me a deal, a couple of postcards and buttons

from a long ago time on the water here. This old world space is about to disappear, dispersed into space.

I thank him and take in more of the town, imagining what it

would be like to live here and taking in a few more shots.

Rob is in the Salvation Army. We walk out to find our own salvation at St

Anselmes Nude beach a few kilometers away.

A sea gull holds forth and we look at the ships, where

exploited, unregulated laborers still lingers just off the shore, beyond reach

of most everyone, hidden plane sight.

Getting closer and close to the beach, we talk about writing

and transcendentalists, the water and the landscape, and its odd resemblance to

the California coast of our college days.

I am so glad I was able to be a small part of that cavalcade

of left coast creative thought, extending stories from the Beats to the Hippies, the Merry Pranksters,

to the punks, the deadheads to the Janes Addiction dread locked groupies of my college days in Southern California.

“Sometimes I look back at my life, as if I were one of the those characters in one of David Hockney’s sunny LA portraits, a neighbor or Isherwood or Joni Mitchell in Laurel Canyon…. Just as Neil Cassidy died and Bob Weir’s daughter Cassidy was born on the same day, there they were, here I am, looking at the story of Dad and Fred, whose death inspired me to be something larger outside myself, connecting my life with a story of activism extending to movements stretching back from Dada and the beats to the movements that have inspired me over the quarter century that he’s been gone….”

“Sometimes I look back at my life, as if I were one of the those characters in one of David Hockney’s sunny LA portraits, a neighbor or Isherwood or Joni Mitchell in Laurel Canyon…. Just as Neil Cassidy died and Bob Weir’s daughter Cassidy was born on the same day, there they were, here I am, looking at the story of Dad and Fred, whose death inspired me to be something larger outside myself, connecting my life with a story of activism extending to movements stretching back from Dada and the beats to the movements that have inspired me over the quarter century that he’s been gone….”

So we rambled on about faith and friends, Dads and

authenticity, schools we could have or never have gone to and roads less

traveled, others well worn. Our path

began to erode as we came closer to the hidden cove where we’d jump into the

freezing water.

The water felt wonderful, cutting my legs like knives, much

colder than the new years polar bear swims of the last couple of years. But we

were alive. Breathing, skipping stones, and talking about our college friend Alice,

who loved Freddy and River Phoenix so many years ago. Its good to know she is still around.

We remembered New Orleans, a road trip through Sewanee,

triumphs, pleasures and some regrets.

Stories coming and going, finding light and receding into the darkness,

not quite ready for the violent brightness of our current moment. Sometimes the light sends us back further into

the cave. Icarus crashes into the sea in all of our lives. Its lovely to chase the sunshine. But it can

be hot when the wings begin to melt. And

how we fall? Yet, what do we do when we fall?

It can be a blessing. We should toast our failures, Carline reminded

Dodi, Scarlett and me so many years ago when Dodi lost her blue belt in

karate. She’d pulled out the

martinelli’s sparking cider and we all toasted to the first of many such

moments, which we hope will not pull us down.

“You have to toast your failures.”

“Look, there is the light house that inspired To the Light

House,” noted Rob, referring to Wolf’s grief after her mother’s passing. The

solitary moment and silence exquisite, the sun shining on the water, as the day

began to warm.

“I think you out coffeed me,” noted Rob, looking at the

lovely café latte sitting in front of me.

It was getting close to 5 pm. So we wandered back, gossiped and laughed.

“You are so lucky to live here,” I nodded, looking at the

sea.

Round after round, we talked and laughed about the past,

reveling in the transformations which bring us to the present, years after we

left our beloved California behind, even when we made mistakes. All of this how we got here is who we are.

“You must always warm a butt plug,” explained Nick, during

the evening’s last round at the Boat House, helping me understand the many

meanings for the term a “Prince Albert.”

Sometime we all hope to slow things down a little, while warming them

up. He loves the stories people share in

bars, shared through face to face memories and tales, not twitter or facebook.

“My friend’s daughter told me about her research in the

urban dictionary. Do you know what a

strawberry cheesecake is?”

“No, but what about felching?” I asked trying to keep up

with the bowdy Irish banter.

A London transplant, he has spent his life working in pub

after pub.

“We ran one that had been inadvertedly dubbed the Felcher

and the philosopher,” noted Nick, referring to a series of pubs with variations on names beginning with F and P. “I had to

call the owner and disabuse him of that one.”

We thanked Nick and everyone. And Rob and I meandered back home by midnight.

A cab came to pick me up for my 24 plus hour journey home at

5 AM, driving me to Newquay, where I’d fly to Gatwick, where I hoped to catch

the 11:30 for Orlando and then possibly make it back to New York by ten or so,

if luck is with me, and we don’t stumble too bad along the way.

God speed Rob. C u

soon. A copy of his new book in

hand. I’d read it all day long.

The car meandered through the woods, between the curves in

the road, dropping me off at 5:40 am, almost two hours before my flight for

London. The full moon is still out. Once

up in the air, the young bartender sitting next to me pulls out the Bell Jar by

Sylvia Plath. I hope her life is happier

than the protagonist I think.

“I love sad stories,” she explains as we chat.

“Those characters seem so familiar to me,” I explain. “I wonder what I would do or would have done

if I had known her.”

I pick up the Scorper and start to read. These characters

feel so familiar. Their lostness, their eerie

encounter with a lost highway of memories of the self and an encounter with an

estranged other, who might have been who you always were or might have

been. We all dance with Oedipus at some

point in our lives. The stranger stares at you and tells you stories about

people you might have known, the rambunctious silly feeling of a literary quiz

our protagonist feels like he’s spent his entire life preparing for, and the

soul emptying loneliness of the everyday.

Narratives of redemption and the petty humiliations of lost connection

feel like stories among old friends. The cavalcade of past girlfriends

remembered remind you. Our protagonist

is invited for a liaison with a new friend.

Yet, unexpected, unwanted visitors join.

“Its not enough to traumatize your memories – your

girlfriends want your stories told in the company of the dead.

‘A fresh start’ you beg as you try to escape. They jab you

with their elbows until you submit to being revisited under the lime trees

gnarled branches and naked trunks.

“You met Natalie in Introduction to Shakespeare, first year

in college. She had come from an

exclusive Prep School in Maralynd, an institution with puritanical Quaker roots

that had evolved into a bohemian experimental laboratory for sex. At eighteen, she’d already had flights with a

dozen other men, including her math teacher. She had shoulder length blond

hair, brown eyes, long swimmer’s legs.

What she saw in you, God knows…. [B]ut you were not about to protest and

soon you would be walking the campus together holding hands.”

Our protagonist eventually meets Natalie’s dad, who sees him

as impotent and the lesson becomes internalized. And soon, he is not able to

perform. And the sad reality of early

lost love sets in. “When you went to parties together, she would gaze over her

shoulder at other men. She started to

hum out loud when you spoke.”

“One night you went to her room and found it locked. On the

other side of the door were noises – noises that stopped when you knocked. The

next morning she had a new friend, a Russian exchange student named Dminitri, a

chain smoker and self-proclaimed nihilist who liked to crush his cigarette butts

into the open pages of books. Soon they

were walking the campus together holding hands.

From her friends you heard that she took the nihilist to lunch with her

famous father. And because Natalie kept

on seeing Dmitri, you suspected the father found the nihilist to his liking.

“The impact of these events lingered. The more you tried to meet other women, the

more you suffered from psychic aftershocks… There passed years of

embarrassingly incompetent flirtations and failed one night stands….”

So the cavalcade of stories and memories meanders

forever. It feels like we all might have

known a Dmitri and a Natelie? Maybe some

of us have? Theres so much to wonder about in this life beyond confines. Italy Calvino reminds us theres no limit to such a story. There are many ways of looking at texts and narratives, memories and friendships, experiences and journeys into nether reality.

They were with me all the way, as were the lessons of

England, the cruelties inflicted, and friends who survive. Didn’t get home till

midnight on Easter, the Scorper read from cover to cover.

No comments:

Post a Comment