"Join us for the launch of Benjamin Heim Shepard’s Illuminations on Market Street: a story about sex and estrangement, AIDS and loss, and other preoccupations in San Francisco. Shepard will be joined by novelist Wayne Hoffman. See you at 4 pm @bgsqd (at Bureau of General Services-Queer Division)

https://www.instagram.com/bgsqd/p/Bv9iMUVlJvn/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1rri6w3kb0pm9"

Photos by Barbara Ross

a full weekend of readings with my friends.

photos courtesy of @thedonniejochum

It was a weekend of readings and

conversations. Dion who recalled Carson

McCullers in Georgia, and Caroline told a story about Renate in Staten Island.

Wayne talked about Allan and Eric and Moe, and Dream Jordan traced a story

about turning hardship into brilliance!!!

“I live with the people I create and it has always

made my essential loneliness less keen,” Carson reminded us in the Heart is a Lonely Hunter.

Be a good vagabond and travel,

preached Donna.

Stories grow such spaces.

“We

are homesick most for the places we have never known,” lamented Carson

At BK9, Caroline read from excerpts

from her magnum opus, The Many

Misfortunes of Renate O’Malley, a story that grew from

the road, across Europe and time, beginning with a few notebooks she found in

her mother’s basement.

And then there was my story on the

third weekend of readings from Illuminations

on Market Street.

When I first moved to New York, everyone was talking about

public sex and public space. The coolest, smartest book out on the topic was by

a group of prevention activists. I always wanted to write a book like them, to

be an activist like them. Sunday at 4 PM, I’d join one of them, Wayne Hoffman,

in a conversation about editing Policing

Public Sex, his volume of pulsing ethnography, before becoming a novelist.

Hoffman wrote about sex wars and hopes, AIDS politics and

struggles for safer promiscuity, through the struggles of activists and their tricks, porn

stars and journalists, trying to navigate an ever transforming in New York City

(see my review below).

To mark the 25th anniversary of Kurt Cobain's death,Wayne Hoffman and I would be reading about Cobain and San

Francisco on Sunday 4/7 at 4:00 at BGSQD, the bookstore at the Center, as part

of an event about my novel Illuminations

on Market Street,

reading from our books, and having a conversation about sex, loss, activism,

writing fiction vs. nonfiction, and more.

Replying to the announcement for the reading with Wayne,

activist Michael Petrelis posted,

“Its time for a new anthology titled, Policing Private Sex, all about HIV transmissions, denying women

reproduction choices and other

intrusions by the state into our bedrooms.”

His story still inspiring.

But before our talk, I would

have to get through a crazy

weekend, a reading with friends on Saturday in Brooklyn, out to my

mom’s house in Princeton, back to Judson, off to Brooklyn, and back.

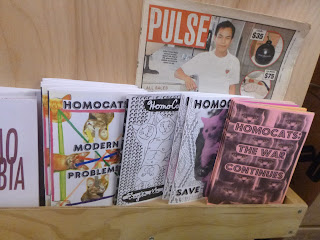

At the Bureau on west 13th street, Hoffman

and I began the panel, reading short

excerpts from our books.

Hoffman read from Sweet

Like Sugar, recalling connecting with a new friend after the death of Kurt

Cobain.

My rock and roll suicides began Ian Curtis and Darby, still

stinging all these years later, I replied as our conversation began as an extended

reflection on HIV, loss, ,and sex

wars in San Francisco and New York.

Mutual friendships with Eric Rofes and Allan

Berube, experiences with

SexPanic! and shared losses connect our stories of heroes and

historians, too many dead before their time.

We’ve talked about that over and over through the last twenty

years, he recalled.

Hoffman asked me about Illuminations:

What kinds of notes were you taking about your own dating life

when you were young and single? A journal? Written scenes? Did you have

“primary source” material from your own life to look back on when you were

writing the book? Or just memories?

It was a daily journal that I began in 1989, I replied,

tracing losses and hopes,

sex and possibilities, anniversaries and pollical awakenings. What started

off somewhat like the Rachel Papers

by Martin Amis, notes about each person, as markers of time,

girls, guys, deaths, gradually

evolving into a story of politics and social movements, as Tiananmen Square

turned to the Velvet Revolution, and the

LA Riots.

And then there were the losses.

Going so badly, I had to reconcile it all.

Back and forth we chatted.

Hoffman asked,

At the end of your book, you write about having the idea to write

this story but being unable to do it for more than 20 years. How would this

book have been different if you’d written it 20 years ago? How different do

your 20s look from the vantage point of…your 40s?

-

At the point when the

notebooks began, I was integrating my

life in everyone else’s stories, collecting oral histories for my first

book.

-

And not sure if I had a

story.

-

After I closed the notebooks in 1995, I moved to Chicago and then New York,

wrote ten other books about ACT UP dovetailing into the Global Justice

Movement, into public space battles and occupy and rebel friendships, and

stories of our kinship networks, coming

closer and closer

together, morphing into my story,

however little plot there was.

-

Twenty years ago, there

would be little literary structure, or voice or aesthetic scaffolding I needed

to mold these notes into something, into a structure, however tenuous. And then on a trip to

Austin, I looked at the sky, had a moment and started writing and writing and

writing and writing and the story from those old notebooks fell into place.

Hoffman noted:

We both made the transition from nonfiction to fiction. What’s the

difference between writing fiction and nonfiction for you? Your book is framed

as a memoir, so you’re leaning into the blurred lines…

It’s a roman a clef, I replied,

a novel about real life. The key

is the space between the fiction and

the nonfiction, the blurry space between the two.

Its better to imagine… as studs said about Blanche DuBois, it

wasn’t that she did not necessarily tell the truth, she told what should have

happened. Objective reality is

boring. Narrative truths are more open

to crisscrossed storylines, between what was and what might have been.

Sometimes it's better to embellish.

Hoffman followed:

I was always slightly frustrated by people assuming Moe Pearlman

was me, even though we have a lot in common, just because it seems a little

insulting to me as a writer, like I can’t create anything other than my own

story. Do you find that people assume you are Cab? How do you respond?

Well, it’s my life but its fiction, I replied.

-

I adore Moe, the

protagonist from Hard.

-

Can I have that slice of

pizza he asked.

-

He’s the most compelling

of characters.

-

And it makes me love you

to see you birthed him.

-

Even if you are not Moe,

I’m sure you asked someone

-

for the pizza crust at

some point.

-

Reading your books it’s

still like I’m watching you have sex and date and walk around ruminating about

it.

-

There is a lot of sex

people say.

-

Yes, that’s the root of

all our stories, from our parents meeting, conception, Freudian family romance,

our separation from that into communities and families of choice, where we try to connect again.

-

I loved watching you

integrate the real sex wars into your fictional

narrative.

Wayne asked:

Have any people you know who you turned into characters read the

book, and recognized themselves? What did they say?

Some have some have not.

Well, most of the people

know.

Some do not acknowledge it

Others have not opened a page.

Wayne followed with the best

question of the day:

What’s your philosophy on writing about sex? I notice that you

avoid a lot of things that men usually include when they write about sex with

women. I don’t really even know what most of the women Cab sleeps with look

like.

Not sure about what other men write about sex.

But I don’t want to describe

the act.

Its more interesting to let

the lights fade.

I don’t want it to be like slimy porn letters.

Its more about the world around the sex, the relationships,

the failures that we have

to cope with.

The kinds of stories

Stephen Zizinczey traces in In

Praise of Elder Women, of war and

exile, goodbyes and hellos.

He writes about women being happy not to be with

him or happy to see him go,

About sex workers who he negotiates for in a time of war, the

conflict being the main subject, not the sex per sex. Most

sex is basically friction Foucault says.

That’s not that interesting, its more about the people creating the friction, but it really is the genesis of

our stories, the sex. Rejecting the

prohibitions and phobias around the

topic is important.

But there is a point when its too much. I’m not sure where we find

that line.

Wayne followed:

You’re not afraid to write about sex that isn’t great – either the

sex itself, or the things that sex involves. You include STDs, abortions, and

stories about rape, in addition to sex that simply doesn’t go well.

Through STH or Straight

to Hell, an x-rated zine, Boyd McDonald fashioned a hybrid of

pornography and political philosophy, writing about going out with guys not

being able to get it up. Same thing with David Feinberg’s stories

in Diseased

Pariah News. Inviting a trick over and not being able to stop bleeding

because of his status or hooking up with someone in act up and then not wanting

more. But the trick moves on to bigger

and brighter pastures.

Kirk

Read writes about sucking and sucking until his john wants him to leave, but he

begs him to let him keep going, even

though he can’t come. Or Moe finally

getting head in the arcade and then the sex cops barge in in Hard.

Isn’t

that what life is all about, the sex police real and imagined bargaining

in and getting in the way. There is

plenty of good sex, but that’s less interesting. It’s the messy stuff that

drives the story.

Yet,

there is something about the way

McDonald wrote about sex, which he thought was extraordinary, gay sex in particular. It was an avatar for freedom of the

body. He felt all men wanted these

sexual encounters. He hated

respectability, wanted us to be raw and authentic. ‘"The truth is the

biggest turn-on" he confessed.

Wayne asked:

Your story takes place before protease inhibitors, and way before

PrEP, when condoms were the only really effective method of having safer sex –

and Cab was enmeshed in a community where HIV was a reality every day. And yet,

during Cab’s sex scenes, it’s remarkably easy for women to give him permission

to toss the condom away, and he’s perfectly eager to do so. Does that reflect

your own experiences with condoms?

Condoms are always the source of narrative tension. They represent possibility to reject

repression that Freud prescribed. But you have to get the damned things on and

keep them on. They are like fucking a

fire hose my Zoe says in the story. To

wear a condom or not to wear a condom, protecting from disease and erections; it’s

the Hamlet question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them? Panics, std’s and pregnancies happen without

them in the stories. But so does fun, so does disease protection. That’s the

mystery the characters must endure over and over.

While Cab remains negative, the shadow of HIV impinges on all his

romances, negotiating sexuality with his partners.

The epidemic created an environment of shame that stigmatized and

froze relationships, caused them to implode.

No one knew what to do, what was safe.

There was always panic.

Maybe this is an unsafe behavior?

Maybe this is safe?

The guidelines for safe sex

changing all the time.

Bleeding gum, it was a world where HIV had created a culture of

shame and fear around sexuality and people absorbed that.

It was a sex negative time.

Even if people were negative, they were frightened of intimacy.

And that changed connection would be, forcing it to forever dance

with separation, as Cab negotiates sexuality, reflecting on an atmosphere of

fear and shame, contending with that.

Wayne wondered:

We’re about the same age, and music seems to play a huge role in

how we think about time and memory. Why is music such a primary way to evoke a

particular time for you?

It’s

everything, connecting Cab with the richness of the culture, while dancing on

the edge of a volcano, Cab living in the most frightening wonderful time of the

era, as Cab is dealing with a maelstrom.

Ironically, he never felt more alive, at the residence, going to shows,

listening to stories, cruising in the Tenderloin, listening to stories.

Music

connects all the feelings – the aspirations, burning ambitions, Cab seeing

Janes Addiction, Hole, and the Husker Du.

Music

was the first social movement I was ever

a part of.

Over

time, punk dovetailed with ACT UP and poetry.

Dad’s

Beat movement, overlapped into music and counterculture and still more

movements ebbing and flowing,

Between

rebel friends and cohorts of activists.

-Its the Madeline in

remembrance-of-things-past: Swanns Way… “Whence could

it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I was conscious that it was

connected with the taste of tea and cake, but that it infinitely transcended

those savours, could not, indeed, be of the same nature as theirs.”

Over the

hour, we talked about the losses and the friends we remember, transcribing

their stories from old tape recordings.

And

the funny sex stories,

And

the sex panics

Over

the last two decades.

And people started to rumble.

We thanked

everyone for coming,

Those

who were characters who found their way into the stories,

Past

and future activist comrades.

Stories

all afternoon long, before we took a final stroll through the Bureau,

Snapped

a few shots in Keith’s bathroom and wandered into the sunny afternoon.

Thanks

for yacking with me Wayne.

I

wrote a review for Hard over a decade ago,

recalling those days.

Skipping the life fantastic in a

hard city.

Hard: A Novel. By Wayne Hoffman. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006, 345 pages. Softcover, $14.95.

On September 7, 1995, in the midst of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's crackdown on sexual commerce in New York City, the AIDS Prevention Action League (APAL) held an event called the "Save Our Sex Party." The gay men's sex wars were just heating up. "APAL decided that the generation of pleasure in the name of community would be a worthy end in itself," APAL member and ACT UP veteran Jim Eigo (2002), one of the event's organizers, recalled. For Eigo, the event was a form of prevention activism. "The fucking onstage, in defiance of a health code, was an education, and it spread its energy to the party-at-large: 450 men of different races, shapes, ages, and classes coming together in a model of supportive, safer public sex" (p.189).

The first scene in Wayne Hoffman's new novel, Hard, begins with a similar sex party cum civil disobedience situated within a crackdown on public sexual culture. The parallels between fiction and New York City cultural history in Hard are many. And Hoffman should know. The year after APAL's Save Our Sex Party, he was one of a group of scholar-activists from New York University's American Studies program who published a volume of critical essays, ethnographies, and historical pieces entitled Policing Public Sex: Queer Politics and the Future of AIDS Activism (South End Press, 1996). The volume included "The History of Gay Bathhouses" as well as Hoffman's "Skipping the Life Fantastic: Coming of Age in the Sexual Devolution."

Policing Public Sex infused an ongoing debate about gay men's sexuality and HIV prevention with a much-needed dose of critical activist perspective. The work immediately found a place between Michael Warner's Fear of Queer Planet and Eve Sedgwick's Epistemology of the Closet as a seminal contribution to the field of queer theory. In much the same ways as ACT UP's cultural activism helped inform Douglas Crimp's queer theory, Policing Public Sex embodied a critical theoretical perspective on AIDS prevention activism.

In the midst of this debate, a number of gay writers with a history of activism suggested that gay men had brought on the second wave of AIDS with their promiscuity, and therefore deserved to have their spaces for public congregation, such as sex clubs, shut down.

The result was a culture war over the meaning of queer sexuality at a time when effective treatments for HIV/AIDS were just beginning to really take hold. The debate would last for the remainder of the decade and well into the next. (1) Yet unlike the feminist sex wars of the 1980s and early 1990's, which resolved themselves with a series of court decisions (see Duggan and Hunter, 1995), this round of the gay men's Sex wars never quite reached a resolution. With no single court ruling to pin down a declarative decision, there are instead many perspectives on the period's implications. Reflecting on the debate, Hoffman (Personal Communication, 29 January 2007) recently noted:

Hard: A Novel. By Wayne Hoffman. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006, 345 pages. Softcover, $14.95.

On September 7, 1995, in the midst of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's crackdown on sexual commerce in New York City, the AIDS Prevention Action League (APAL) held an event called the "Save Our Sex Party." The gay men's sex wars were just heating up. "APAL decided that the generation of pleasure in the name of community would be a worthy end in itself," APAL member and ACT UP veteran Jim Eigo (2002), one of the event's organizers, recalled. For Eigo, the event was a form of prevention activism. "The fucking onstage, in defiance of a health code, was an education, and it spread its energy to the party-at-large: 450 men of different races, shapes, ages, and classes coming together in a model of supportive, safer public sex" (p.189).

The first scene in Wayne Hoffman's new novel, Hard, begins with a similar sex party cum civil disobedience situated within a crackdown on public sexual culture. The parallels between fiction and New York City cultural history in Hard are many. And Hoffman should know. The year after APAL's Save Our Sex Party, he was one of a group of scholar-activists from New York University's American Studies program who published a volume of critical essays, ethnographies, and historical pieces entitled Policing Public Sex: Queer Politics and the Future of AIDS Activism (South End Press, 1996). The volume included "The History of Gay Bathhouses" as well as Hoffman's "Skipping the Life Fantastic: Coming of Age in the Sexual Devolution."

Policing Public Sex infused an ongoing debate about gay men's sexuality and HIV prevention with a much-needed dose of critical activist perspective. The work immediately found a place between Michael Warner's Fear of Queer Planet and Eve Sedgwick's Epistemology of the Closet as a seminal contribution to the field of queer theory. In much the same ways as ACT UP's cultural activism helped inform Douglas Crimp's queer theory, Policing Public Sex embodied a critical theoretical perspective on AIDS prevention activism.

In the midst of this debate, a number of gay writers with a history of activism suggested that gay men had brought on the second wave of AIDS with their promiscuity, and therefore deserved to have their spaces for public congregation, such as sex clubs, shut down.

The result was a culture war over the meaning of queer sexuality at a time when effective treatments for HIV/AIDS were just beginning to really take hold. The debate would last for the remainder of the decade and well into the next. (1) Yet unlike the feminist sex wars of the 1980s and early 1990's, which resolved themselves with a series of court decisions (see Duggan and Hunter, 1995), this round of the gay men's Sex wars never quite reached a resolution. With no single court ruling to pin down a declarative decision, there are instead many perspectives on the period's implications. Reflecting on the debate, Hoffman (Personal Communication, 29 January 2007) recently noted:

I like to think that there wasn't a clear winner in the sex

wars, too, but in most ways there were winners. We still

have monitors in our sex clubs, most of them are gone

and will never return, the zoning laws are still on the

books, and a whole generation of gay men will grow

up not even knowing what might be possible. Yes, we

still have some things open to us, and yes, are inventive

enough to create new spaces under the radar and keep

things from shutting down completely. But the anti-sex

activists were mostly successful in their ridiculous quest.

Of course, the fact that their quest had nothing really to

do with HIV prevention doesn't matter at this point;

some of us knew all along.

There was no follow-up to the critically acclaimed Policing Public Sex. To my knowledge, none of the members the collective who edited Policing Public Sex finished at NYU. For his part, Hoffman went on to edit a gay newspaper in New York City. And, finally, a decade after "Skipping the Life Fantastic," he once again delves into the sex wars. Yet instead of another nonfiction anthology or a critical essay, this time he has situated the moral questions at the center of the sex wars within a novel.

The protagonist of Hard, which reads like a roman de clef, is Moe, a young graduate student in and out of NYU studying queer theory, who goes on to edit a gay newspaper in New York City. Like Matt Bernstein Sycamore's 2003 novel Pulling Taffy, Hard blurs the lines between fiction and history as it details the subterranean struggles to survive and thrive in the face of the homogenization steamroller represented by the New York sex crackdown.

Hoffman traces Moe's adventures through boyfriends, safer promiscuity, the sex clubs, tearooms, and the ups and downs of life during the Giuliani crackdown of the 1990s. As noted above, the story begins with a sex party, a fundraiser for the Association to Save Sex (ASS). Like "Justice"--a fictional trope for ACT UP in Sara Schulman's novel People in Trouble--ASS offers a fictionalized representation of a group that sounds not unlike the short-lived APAL or SexPanic, a spin-off from APAL and ACT UP that turned bickering into a fine art. While Hoffman makes use of humor to detail the struggles of these sexual civil liberties activists, the issues they face are real.

The party that opens the book is lots of fun. Characters meet, talk, hook up, and--like many moments of public sexual contact in Giuliani's New York--it is not long before the party is broken up by the sex police: "More than fifty men filed out the back door and into the snow," Hoffman writes, highlighting the banal administrative detail suggestive of Michel Foucault's prophesy that sex eventually would become a police matter. "The police had cleared out the basement club in a matter of minutes," Hoffman writes. "They didn't have to rush people too much.... The cops let everyone retrieve their bags from the coat check, but didn't give anyone ... time to put their clothes on before ushering them ... to the sidewalk" (p. 9).

As Moe mills around in the West Village that night, just outside the meatpacking district, he feels a tap on his shoulder. "Hello, Mr. Pearlman," Frank Desoto, the editor of Outrageous, a gay vanity rag, greets him. "I understand you were one of the organizers of tonight's soirre" (p. 10). Frank is a reactionary, generally cantankerous, increasingly conservative writer with a long history of gay activism, much like's today's Larry Kramer. He happened to be around ready to report just as the club crackdown began, with pen in hand to document the event. Frank interviews Moe about the party:

"Tell me, were there condoms provided at your party?"

"No Frank, it was a jack-off party. There were no condoms" (p.10).

Frank grills Moe about the event's intentions, suggesting safer sex, "is dangerous, that promiscuity is inherently unhealthy in the age of AIDS," (p. 10). Moe responds:

Sex venues can be great places to promote safe sex, and

that the more exciting safe sex is, the less people will be

driven to have unsafe sex. HIV doesn't have to fundamentally

change your sex life. Our desires don't have to go unsatisfied.

Hot sex can endure both this epidemic and the mayor's ongoing

campaign to close sex spaces. (p. 10)

Seeing Frank writing down every word, Moe realizes he probably should not have said so much, especially without permission from ASS. After the interview, Moe runs into Aaron: "I saw you talking with your reporter pal," Aaron said. "He got here awfully fast, if you know what I mean. What did he want?" (p. 12). Moe explains. "We'll see what he writes," they both agree. "This could be big news. With all the cops out here, it looks like Stonewall" (p. 11).

The Stonewall reference immediately opens up a new set of questions. During the Stonewall Riots of June 1969, queers fought back against police harassment, as they had on several previous occasions including at Compton's Cafeteria in San Francisco and Cooper's Donuts in Los Angeles during the decade before gay liberation. The message of these altercations was that queers would fight back when the state cracked down on their gathering spaces. The politics of gay liberation involved freedom of thought, expression, association, and sexuality. So, Moe wonders, why weren't queers fighting the crackdowns on public sexual culture in the 1990s?

When he finally sees Frank's sensationalistic report about the raid in Outrageous, Moe regrets having agreed to the interview. In years past, gay activists had fought the likes of Anita Bryant and Pat Buchanan over their anti-liberation rhetoric. But with the gay men's sex wars, gay men were now being attacked with similar bile by other gay men. This, of course, is Hoffman's point. After so many years of loss, let-downs, changes, and the ravages of AIDS, whatever solidarity might have been left over from the Gay liberation years during which Frank came of age as an activist was long diminished. "Sure he had friends today, but everyone was on guard, afraid to get too close for fear of losing another loved one," Hoffman writes. "Frank had changed too, and he knew it. He felt hard" (p. 122). The party does not last long, yet the aftermath between the introduced characters trickles through the volume.

The week after the party, at a regular meeting of the Alliance, Moe has some explaining to do, as he was not authorized to serve as a media spokesman. Yet even after going over the article, the group is unable to see the forest for the trees and get over its internal rivalries. Moe finds little support from within the group to actually fight back. The more the neoliberal and progrowth mayor pushes to clean up public space--with gay journalists like Frank DeSoto cheering and supporting the crackdown--the more timid the Alliance becomes. And this in the town that brought the world the Gay Liberation Front and ACT UP!

On the way out of the futile meeting, Moe goes to his favorite tearoom to let off a little steam. Instead of his usual position on his knees, a horny, pissed-off Moe opts instead to stand and let someone else deliver. Having found a taker, Moe starts to relax, but a knock on the door disturbs the scene: "Hey you in there! Open up! One guy per booth! One person per booth. You want to get us shut down?" While Moe insists he's been coming to the space for years, complaints are to no avail. "That was then, this is now, buddy," the monitor told him, wagging a finger at the new poster: One per Booth. No Exceptions. "Now get out of here" (p. 44). Throughout the novel, we witness the public sexual geography of Moe's Manhattan diminish.

Without these spaces, the city was becoming harder. The double entendre is never quite explained, yet it drives the story. On the one hand, queers are left with fewer places for contact, pleasure, and release; thus, they are left harder. Wilhelm Reich suggested that the seeds of fascism are planted within such a lack of connection between mind and body, between desire and realization. Within this void of actualization, suppression of feeling supersedes empathy and gives rise to the drive to control one's self and others. The result in literature is characters like the closeted fascist general longing for contact in Alberto Moravia's novel about Mussolini's Italy, The Conformist. These roots also manifest themselves within the politics of the Christian Right.

While Hoffman thankfully avoids psychobabble, he does make the point that Frank DeSoto is loveless. All the while, the democratic, highly accessible public spaces in New York--which author Samuel R. Delany famously celebrated in his 1999 memoir Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, for providing an arena for cross-class contact--are steadily diminishing. "There wasn't much truly public sex left in New York by the time Moe arrived in the mid-1990s," Hoffman writes, listing the losses, space by space.

As public sexual spaces become more and more sparse, Moe finds a class-bound virtual world of Internet hook-ups in private bedrooms. Of course, the limitation of this scenario is that there is little of Delany's vaunted intermingling between people of different worlds. On the Internet, only those with the resources to afford a computer, a connection, and their own bedroom can play; those without are often left out. Nevertheless, Moe thrives: "Moe got into online sex. Not cybersex, but real sex arranged over the Internet. The fact that he didn't have to leave the comfort of his own apartment was particularly appealing to Moe" (p. 64). Hoffman treats the reader to some funny, Woody Allen-like moments through Moe's exploits, successes, and failures in his ongoing love affair with no small portion of the gay men within walking distance from his West Village apartment.

Some of Hoffman's richest words are left for his unlikely gay critics, such as one of his professors at NYU. Early in the novel, we are treated to the life of a graduate student as Moe traces the ins and outs of the undemocratic world of graduate school at NYU. Moe, like Hoffman, is deeply involved in activist struggles to preserve the city's public sexual culture and his own practice of safer promiscuity. Yet his critical praxis takes him in directions that challenge the theoretical doctrine of his queer theory professor at NYU, where some of the most prominent scholars of queer theory have made names for themselves. On one occasion, Moe questions the assumption that the term "gay" is simply a bygone historical category, and is roundly chastised by his professor. "Moe, I'm very disappointed in this presentation. It seems that after three months in this class, you're still heavily invested in the so-called 'gay community, '" his professor bemoans. "We've discussed at great length how this notion of gayness has been socially constructed, as well as the concept of community in general. These aren't naturally occurring categories--they're strategic, politically useful shorthand perhaps, but they're not real." She concludes, "You haven't learned anything from this class" (p. 90).

Moe is stunned. No student had received this sort of treatment all semester. Instead of the respectful, engaged discussion he had expected in graduate school, he finds that even in the realm of queer theory, there is little room for differing points of view or spirited dialogue among opposing viewpoints; there are only right and wrong answers. Unwilling to be belittled, Mac drops out of the NYU American Studies program and decides to write about queer New York full time for the gay press. Implicit within this story is the idea that there is more honest exchange of thought within the marketplace of ideas in journalism than there is in the academy.

What emerges in Hard is the image of an academic field in need of an infusion of authenticity, some of the praxis born of its early interplay between the scholarship and activist engagement. Yet instead of an image of queer theorists borrowing from the lessons of ACT UP to help queer theory function as an embodiment of AIDS activism, Mac's conflict is a snapshot of a field growing stale within its hallowed confines. In the years since the peak of the gay men's sex wars--during which academics sought to influence the tone of the debate, only to find that many queer activists did not agree with or even understand their analysis--the divide between the academy and street activism has become increasingly pronounced. Hoffman traces the fictional parallel between academic engagement and disengagement with activism in a thoughtful and telling fashion.

While much of the book's plot is driven by the workings of activism, politics, media, and career concerns, the moments that move the story forward are the randy exploits of Hoffman's alter ego. Moe makes his way through the world like a gay Alexander Portnoy from the 1969 Philip Roth novel, Portnoy's Complaint, with a twisted queer Jewish sensibility. Mac is a resilient, playful character, and he needs as much humor as he can get, especially as the sex wars overlap with his own complicated life of sex, tricks, jobs, and occasional boyfriends. Jobs and political allies come and go. Much of the struggle is ephemeral.

Although its jokes are many, Hard--as its title implies--is a tough story of a world in which the bad guys get little comeuppance. The conservatives are rewarded, and the sex wars trudge forward with no clear resolution. The city changes, relationships die, sex continues, and the promise of urban space remains, albeit in an altered form. Toward the end of the story, Mac is invited by his best friend and former lover to join him in a move to Washington, DC. The sex wars are lost, the Alliance has faded, and so has the newspaper gig that enabled Mac's graceful exit from NYU. In between jobs and weighing two different offers, one of which was born of a conversation during a Seder, the other as part of the flirtation before a sex date, Mac continues to revel in the energy of old New York City. For anyone interested in the trajectory of queer urban living, Hard is the most telling of volumes.

References

Duggan, L. & Hunter, N. (1995). Sex wars: Sexual dissent and political culture. New York: Routledge.

Eigo, J. (2002). The city as body politics/The body as city unto itself. In B. Shepard & R. Hayduk (Eds.), From ACT UP to the WTO (pp. 178-195). New York: Verso.

Notes

(1.) For a brief review of the gay man's sex wars, see Warner's (1999) The Trouble with Normal (Free Press) and Shephard's forthcoming Queer Political Performance and Protest: Play, Pleasure, and Social Movement (Routledge).

Reviewed by Benjamin Shepard, Department of Human Services, New York City College of Technology/ CUNY, 330 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201. E-mail: benshepard@mindspring.com

COPYRIGHT 2008 Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality,

Inc.

Copyright 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment