| |||||||||||||||

| Hanging around Prague. |

We woke late and made our way out into the city,

looking at what Prague has been and is becoming.

Kafka used to take the same walk.

“The dark corners, the secretive passages, the dirty, impenetrable

windows, dingy courtyards, noisy pubs, and closed taverns still live within

us. We walk through the wide streets of

the newly built city. Yet our steps and

glances are unsure. Inwardly we still

tremble as we did in the old narrow streets of misery. Our hearts still do not sense anything of the

renewal which was carried out. The

unhealthy Jewish ghetto is more palpable in us then the hygienic new city

around us. Awake, we are wandering through

the dream, we ourselves just specters od times past,” Frank Kafka.

We walked through modern Prague thinking about the

layers of Prague that are there, turned past post the opera house where Mozart

premiered Don Giovanni, walked past a casino, made our way past the gothic

Powder Tower and the Arts Nouveau Municipal House, wandered through the market,

could not find what we were looking for, and stumbled into the Museum of

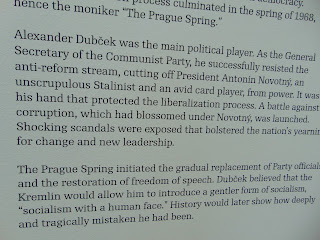

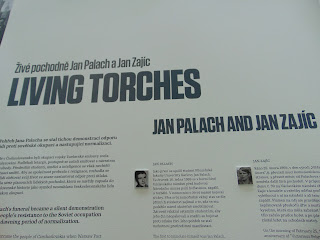

Communism. There we explored the stories

of this extraordinary country and occupations, revolutions, etc. Much of the terrain of the Nazi and Soviet

occupations felt familiar. But the

stories of migration, of people who made lives for themselves here during the

Soviet years, the friends they created, the marriages to get out, the struggle

to resist, these felt compelling. For some,

the Velvet Revolution was the triumph of a lifetime; for others, friendships

could not endure the loss of a common enemy. The movement was completed; the

Wall was transformed into a space for friendship and democracy. But history

would lurch on.

Still, taking a minute to look back was useful. The video of the students out in the streets in

1989, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the November 17, 1939 Nazi attack on

Czech universities, drawing a parallel between the Nazis and the Soviets was

striking. Undercover police tried to

push the rally to move to Vysehrad, but the crowd called for the procession to

go to Weneceslas Square. There police stood in their way. With their hands up, students walked,

pointing out their hands were open, sitting down as the police in riot gear

moved in to beat them. Some pushed back.

But mostly they sat. Over the

weeks of that heady year, a lot of people fought back, mostly peacefully. But sometimes they did swing back at the

police with their batons.

And gradually, the Velvet Revolution took hold. The police power receded. Gorbachev did not call the Soviet tanks to

roll in as they had in 1968.

The struggle moved forward.

The playwright became president.

“Truth and love overcome lies and hate,” declared

Havel.

And Prague opened up to the West, for better or

worse. A generation saw the revolution

on tv. And poured into the space.

Reviewing this history as our president deflects and

tweets and congress maneuvers to take away healthcare, an eerie feeling takes

hold. We hope the US will be a place

where truth and love can supersede lies and hate. But its not easy. I’m not as confident as I used

to be.

“Human rights are universal and indivisible,” Havel

told a joint session of the US congress after the revolution. “If it is denied

to anyone in the world, it is therefore denied, indirectly to all people. This is why we cannot remain silent in the

face of evil or violence. Silence merely

encourages them.”

The city of Prague has rarely been silent.

After lunch and a siesta, we made our way to the Old

Jewish Cemetery, with its layers of graves, and synagogues memorial for the

80,000 Jews killed here during the Nazi years. Name after name are listed

there, Schulman, Fishman, names of friends in the US, whose distant relatives

may have passed through here.

We walked through Kafka’s steps and kept on looking

for something in the city.

No comments:

Post a Comment